Trigger Warning and Disclaimer: the content that you are about to read contains graphic and sensitive experiences. The opinions and opinions expressed in this piece solely reflect the author's views and not Andariya's. Reader discretion is advised. Read our full editorial notice here.

All photos are credited to the author.

Has Public Policy failed in Sudan?

Today and more than yesterday, public policy carries a growing weight of expectation. Hopes and ambitions are increasingly pinned on the promise of policy to solve society’s most pressing challenges. Public policy is being positioned as the tool that will address everything from inequality to educational reform to conflict resolution. As if it has become the magic tool to solve all problems.

And yet, it keeps failing.

Our main hypothesis here is that while it may be too early to declare its failure in tackling the strategic questions of our time, public policy has shown limited success in resolving the everyday struggles that citizens face. Access to healthcare, decent education, stable livelihoods, and basic safety continue to evade millions. If this pattern of under-performance continues—where policy is celebrated in media but collapses in practice—then states themselves risk erosion of both their legitimacy and foundations.

I am here arguing that the failure of public policy in Sudan can be traced to one or more of three main factors: government institutions, civil society and local communities, and the way public policy is taught. As for the first two factors, many explained and talked about them in their research. For example, Dr Atta El-Bathani -a Sudanese politician and policy advisor, has discussed the dilemma of political transition in Sudan in 2023. He pointed to what he calls a governance-crisis rooted in power structures, elite incapability to lead the government, and lack of historical settlement- all of which affect policy implementation.

Community participation during December revolution- Transitional-Period Agreement Signing Day- 17th August 2019

What is happening and why?

Sudanese government institutions suffer from chronic fragility. Ministries and public agencies are underfunded, understaffed, and lack the technical capacity to translate policy into action. Even when policies are made, they frequently lack clear implementation mechanisms, monitoring systems, or allocated budgets.

Making the matter worse, policies are usually compounded by the politicization of state institutions, especially under decades of dictators’ rules. Institutions have always been tools of political consolidation rather than public service. Widespread corruption and mismanagement further hollow out the system, with significant portions of funds diverted before reaching intended beneficiaries.

The state itself remains institutionally weak, while real power is often concentrated in the military, creating a distorted governance structure. Political instability further compounds these issues, disrupting the planning or the implementation or both.

Another major issue within the government is the lack of reliable data and monitoring systems, which leaves decision-makers without the tools to plan properly, assess needs, or measure impact. At the same time, a huge capacity gap among the government employees hinders implementation, as many civil servants lack the training, resources, or authority. Meanwhile, heavy reliance on donor or community funding imposes external priorities and short-term project cycles that prevent the development of the country.

Equally important is the exclusion of civil society and local communities. Public policy in Sudan has long been a top-down process, where decisions are made by elites with little regard for the voices of people. Civil society organizations are often marginalized, especially when they are seen as politically threatening. Participation, when it exists, is usually symbolic or externally driven by donor requirements. This disconnect leads to policies that are technically sound on paper but ineffective or resisted on the ground.

Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, as one of the leading institutions that teach Public Policy programs in the MENA region with the highest number of Sudanese Graduates.

Pedagogy: Teaching Policy Makers how to Fail

What I want to discuss in more depth in this article is one of the most underexposed yet deeply impacting factor contributing to the persistent failure of public policy in Sudan: it lies in the way it is taught or what we can call Pedagogical (methods, theories, and practices of teaching and education). This pedagogical definition -how, where, and why policy is conceptualized and taught-shapes not only what future policymakers know but how they think, what questions they ask and prioritize, and how they engage with institutions and people.

Despite the growing number of programs/universities/centers/think-tanks offering public policy degrees or certificates, both inside and outside Sudan -in a formal or informal educational way, alongside the increasing number of graduates, policy outcomes remain questionable. This suggests a deeper problem within the teaching process itself. The issues can be categorized into institutional issues, the instructors or the teachers, the curriculum, and the environment.

Instructor wise, the teaching process is rarely neutral. Instructors bring their own political and ideological biases to the classroom. In Sudan, especially during periods of the Inqaz regime, academic freedom was severely limited. This has resulted in a generation of graduates whose education has been shaped by dominant state narratives, with little space for critical perspectives. Moreover, academic programs that teach public policy in Sudan are too often isolated from the practical realities of governance. There is little engagement between universities/centers and the institutions responsible for public policy.

Students in Sudan rarely gain hands on experience through internships, fieldwork, or applied research. Faculty are often disconnected from policy-making circles, and the curriculum is shaped more by academic convention than by the demands of the real world. This divide between theory and practice produces graduates who are well-versed in abstract frameworks but unprepared for the political and institutional complexity they will face in actual policy environments.

When public policy education takes place outside Sudan, it faces a different set of problems. Donor influence complicates the issue. Many public policy programs are funded or supported by international institutes, who often shape the curriculum to reflect their priorities. Much of what is taught to Sudanese students is based on models developed in very different institutional and political contexts. So, emphasis is placed on “good governance,” “public financial management,” and “transparency,” while politically charged topics such as land reform, inequality, or security policy are obscured. This external orientation creates an educational environment that privileges adaptation over critique and transformation.

For example, Sahar El Asad -a researcher from University of Cambridge, emphasize that the dependence on Western-driven frameworks and funding, created tensions in execution of educational policies during emergencies in Sudan.

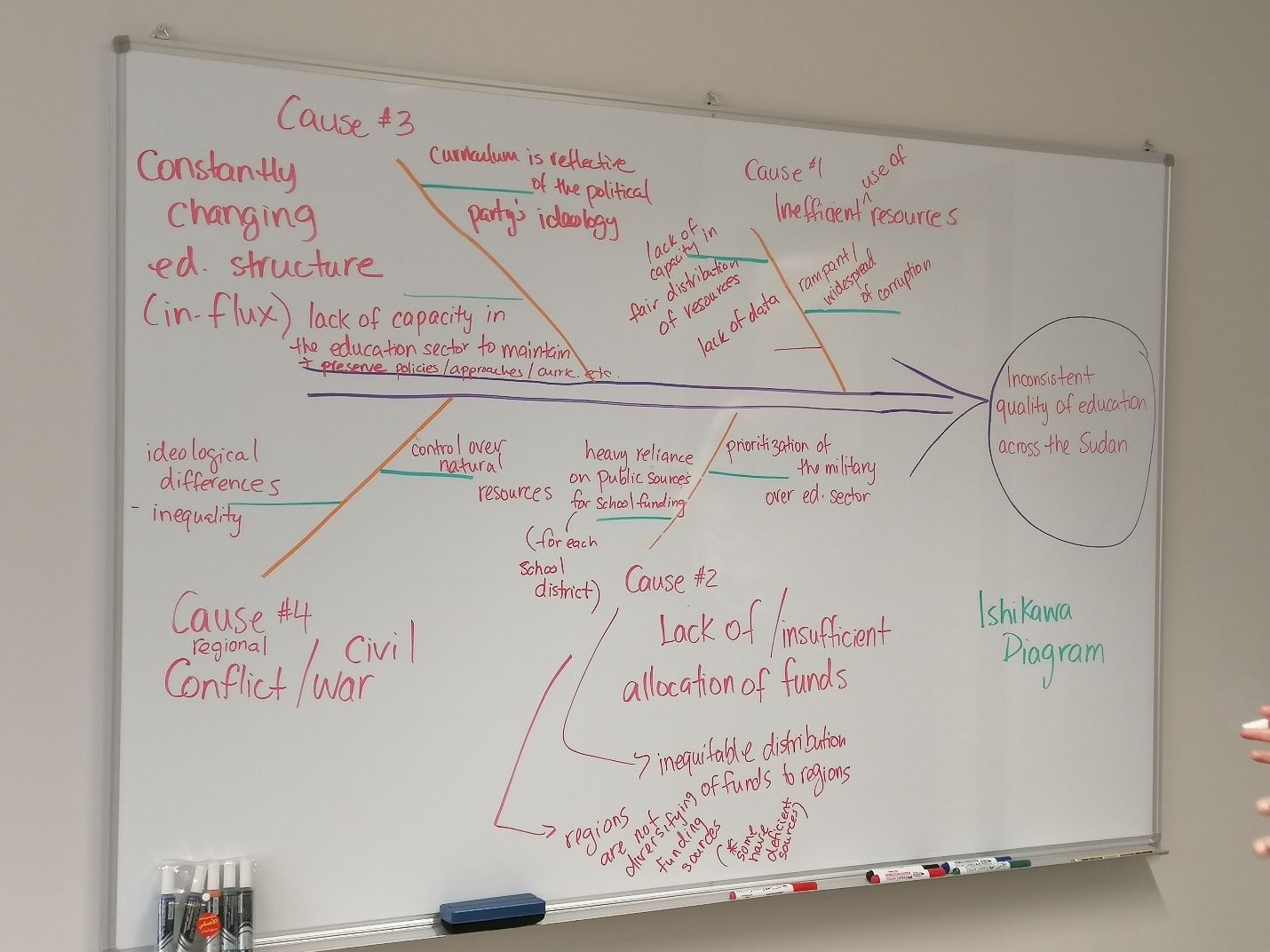

Ishikawa Diagram as one of the tools used during a Public Policy workshop, 2020

Also, when students are taught using examples from other Arab World countries or America, they struggle to see how these ideas apply in a country where ministries lack basic capacity, where policy-making is dependent on individual not institutional processes, and where the rule of law is fragile.

Detachment from Local Realities

This detachment from local realities is not just a question of context -it’s also a matter of knowledge hierarchy. Western knowledge systems dominate, while local histories, practices, and forms of governance are dismissed as informal, outdated, or irrelevant. As a result, the students return home equipped with concepts that are difficult to translate into action within the constraints of a fragmented system.

Lastly and most importantly, public policy is frequently framed as standard science -rather than considering it a technical tool- divorced from its political and social roots. Students are taught to use tools- statistics, cost-benefit analyses, monitoring indicators -without fully understanding the power relations, institutional cultures, and societal dynamics.

However, and without understanding how political power, economic interests and ideologies interact, students are left with a surface-level view of policy making. They may know how to design a policy document or conduct a stakeholder analysis, but they lack the tools to understand why some policies are adopted while others are blocked, why reforms stall, or why institutions remain resistant to change. So, this way of seeing the Public Policy needs to be revisited as the Policy Analyst must remain humble-aware that technical tools alone are insufficient without the politics, economic, social, anthropology, and other core sciences.

Together, these issues point to a deeper crisis in how we understand and teach public policy. The failure of public policy in Sudan cannot be separated from the ways in which it is taught. Pedagogy matters—not only in shaping individual competencies but in constructing the broader institutional foundations upon which policy decisions rest while it remains politically necessary. Without it, we will continue producing skilled individuals trapped in unworkable systems, fluent in global but unable to drive meaningful changes in their own societies.

A Path Forward: Toward a Public Policy that Works

In conclusion, the situation is not hopeless. However, it requires a radical shift in how we think about teaching public policy in Sudan and for Sudanese people. Rather than the western models, we can ground policy teaching in Sudan’s lived realities, integrating historical context, political economy, and social engagement. Curriculum design must involve practitioners, local communities, and politicians who can offer experience and insight rather than abstract theory.

Additionally, teaching public policy must advocate for humility and critical thinking. We must teach the students to ask a very important question alongside the question of who benefits from this policy and who is excluded, which is “what informal systems will challenge or sustain policy reform?” This shift will not only improve our ability to design better policies, but also to implement them with consciousness and better predictability of risks and blockers.

Read "Education for new Era: What Education in Sudan has lost from Ingaz-Decentralization?" by the author here.