Introduction

Throughout history, humanity has endured the ravages of war and the harsh realities of armed conflict, destruction whose effects go far beyond individuals and their personal property, or even state infrastructure and vital facilities. This devastation extends to human, cultural, and civilizational heritage, which is an inseparable part of a nation’s memory and history. Any harm inflicted on this heritage poses a direct threat to identity, consciousness, and collective memory.

Since April 2023, the war in Sudan has not only destroyed lives and infrastructure, but also struck a deep blow to the very core of culture, education, and libraries. Amid death, devastation, and mass displacement to neighboring countries; amid the spread of malnutrition, cholera, and the suffering caused by violence against women, including both individual and mass rape, and the violation of human rights, buildings have been collapsing in cities and villages across Sudan. Silent shelves have fallen without a sound; books torn apart, libraries looted, and intellectual dreams faded into nothing.

The war that began on April 15 did not merely devastate lives and infrastructure, it delivered a painful blow to the heart of Sudan’s cultural and educational landscape.

This article explores the profound impact of armed conflict on public and university libraries in Sudan, drawing on real-life examples from Khartoum, Sennar, Madani, Nyala, and El-Fasher. It also examines Iraq’s experience with cultural heritage destruction and the attempts to reclaim it, while reviewing international legal frameworks for the protection of cultural heritage during armed conflicts.

Background: the emergence of education and libraries in Sudan

Sudan has known formal education since the era of the Turkiyah (1821–1885), and it flourished during the British-Egyptian colonial period, when the first modern schools were established. This was followed by the founding of Gordon Memorial College in 1902, which later became the University of Khartoum.

With independence in 1956, the higher education sector expanded significantly, accompanied by the emergence of well-stocked university libraries, along with public libraries and cultural centers in major cities. Before the war, government reported that Sudan had 39 public universities and 25 private ones, with approximately 700,000 students enrolled and 14,000 university lecturers, of whom around 8,000 held doctoral degrees.

As for libraries, the first was established in 1902 during British colonial rule under the name “Sudan Bookshop.” The book market flourished after independence in the 1950s. However, the number of libraries across the country has declined significantly in recent years, as has been the case in many Arab countries.

University libraries in Sudan began to emerge in the early 20th century with the establishment of higher education institutions, intended to support academic programs and serve the broader goals of these institutions.

One of the earliest university libraries was that of the Omdurman Scientific Institute, founded in 1912. It housed seminal works in Arabic and Islamic sciences taught at the institute. Contributions and donations from local citizens played a key role in expanding the library’s collection. The library grew alongside the institute itself. In 1965, the institute became the College of Islamic and Arabic Studies, and the library’s collection reached about 9,000 volumes. With the college’s transformation into a university, the library further expanded, and branch libraries were established in the faculties of Arts, Sharia and Law, and Da'wa and Media.

The second major university library was that of the University of Khartoum, which remains the largest academic library in the country. Established in 1945, it consolidated the libraries of several high schools, which collectively housed around 300,000 volumes, along with the remnants of Gordon College’s collection. Dr. Glass Newbold also donated his private library, containing 2,000 volumes, to the university’s main library.

In 1960, UNESCO appointed expert Sewell to visit Sudan and propose a national plan for libraries and information systems. He laid down initial frameworks for library development. Later, in 1971, UNESCO sent another expert, Parker, to develop a model plan specific to Sudan.

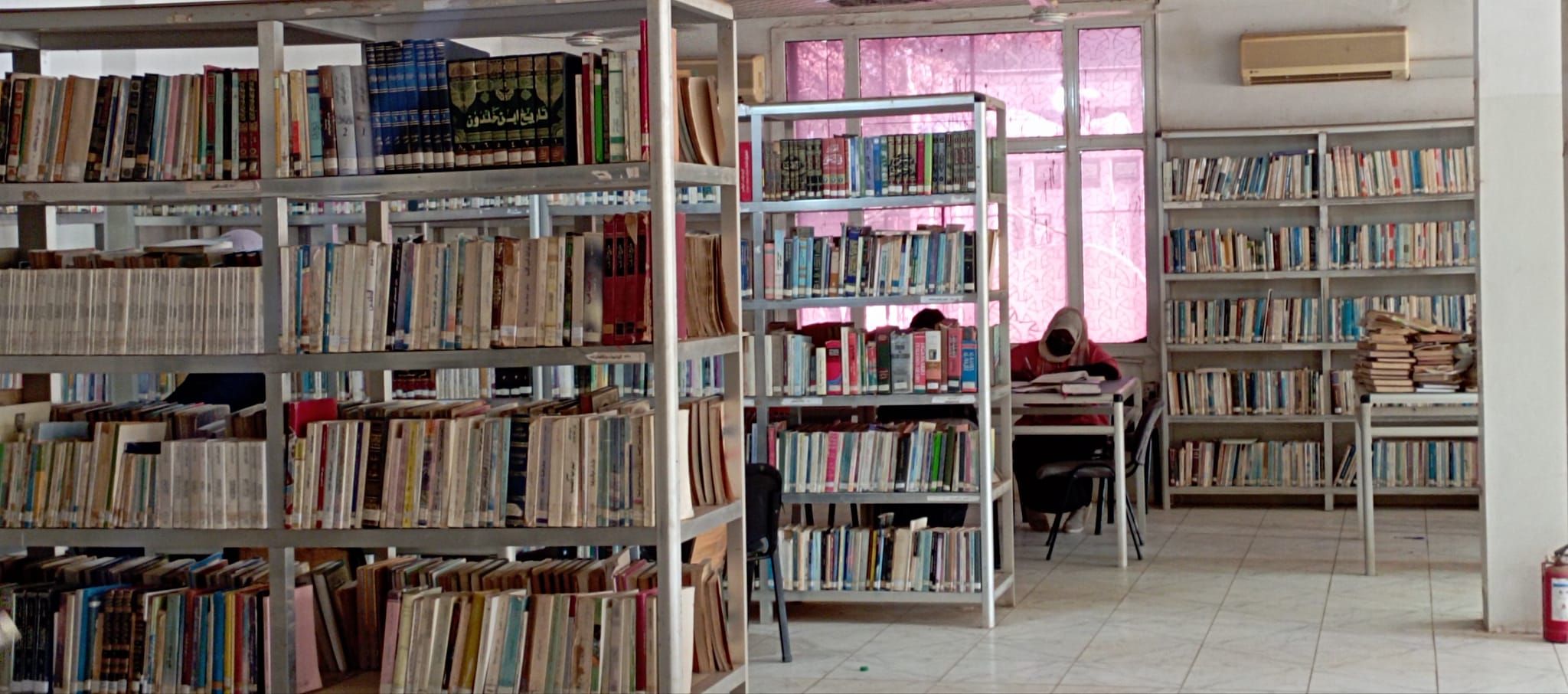

Throughout these periods, and until the outbreak of the most recent war, libraries in Sudan were never just repositories for books. They were vibrant spaces for awareness, dialogue, and exchange, especially during moments of democratic resurgence and cultural openness. Library networks extended to serve regional universities and local communities, offering a refuge for students, researchers, and general readers alike, until the latest war shattered decades of progress.

Public and University Libraries: a memory crumbling under fire

University Libraries

1. Mohammed Omer Bashir Center Library – Omdurman Ahlia University

We, the students of Ahlia University, used to take pride in having this rare intellectual beacon at our fingertips, a center whose value wasn't measured by the number of shelves, but by its depth, its impact, and the questions it left us with. At the heart of Omdurman Ahlia University, nestled among its old hallways, something still shone amidst the surrounding destruction: the Mohammed Omer Bashir Center for Sudanese Studies. It was not just a building, it was a living memory, one we were humbled by and honored to have.

When lectures were canceled, we would rush there with quiet joy, searching for ourselves in the pages of history. We flipped through Al-Tabaqat, explored the studies of Spencer Trimingham, and delved into Mohammed Omer Bashir’s writings on Sudan, its diversity, its many languages and cultures. Every document led to another. Every footnote opened a door to understanding this country we love, despite everything.

It wasn’t just the bookshelves that drew us in, but also the discussion hall, a space for debate and dialogue, where intellectual laziness had no place, and silence was not allowed. There, we exchanged views, disagreed, and raised our voices with the big questions, about identity, the state, and justice.

The author at the Democracy Seminar at the Mohammed Omer Bashir Center for Sudanese Studies – Omdurman Ahlia University. Source: Al-Jaily Ahmed

Then came April 15. A war that does not distinguish between a priceless document and a discarded piece of paper. The center was forcefully opened, and our dreams were stolen from its shelves. Rare books and invaluable documents disappeared as though they had never existed. And now, we write about it as one writes about the missing, with grief, with sorrow, and with a longing that cannot be healed.

Rare historical books and manuscripts were reduced to ashes due to a fire that broke out at the Mohamed Omar Basheer Center for Sudanese Studies library. Source: Al-Jaily Ahmed

2. Faculty of Education Library – University of Sennar / Sinja City

The Faculty of Education Library at the University of Sennar is located west of Al-Mawlid Square and north of the Ministry of Education. It was looted and vandalized following the entry of Rapid Support Forces into the city on June 29, 2024.

The attackers didn’t stop at stealing the library’s infrastructure and equipment, they threw books to the ground with utter disregard, leaving behind a heartbreaking scene: a neglected knowledge hub, in a space that once held the minds of aspiring students.

Public Libraries

1. Nyala Cultural Library

The Nyala Cultural Library was one of the most prominent cultural initiatives to emerge shortly before the war. It was established in 2022 with support from the "Nirvana Center" and was located within the Ministry of Information building, west of Al-Husseini Square, between Nyala Teaching Hospital to the west and the army headquarters to the north. From the earliest days of the war, the library was subjected to direct shelling, which resulted in its complete destruction and the burning of its contents.

Nirvana Cultural Library, Nyala. Source: The library’s Facebook page

The library had served as a space for free reading and the hosting of literary and cultural forums. It offered book lending services to readers and was considered a cultural lifeline for the city’s youth and students. Its destruction came as a devastating blow to the fragile cultural memory of the city.

2. Wad Madani Public Library

Located near the main market in Wad Madani, this library was looted and vandalized during the clashes that took place in the city. Though it wasn’t directly bombed, what occurred was enough to bring all its cultural activity to a complete halt.

Before the war, the library played a central role in supporting students, providing access to books, and organizing seminars and cultural programs.

Wad Madani Public Library. Source: The library’s Facebook page.

Iraq: a comparison of the loss and recovery of cultural heritage

From the founding of the Iraqi state until 2003, heritage was a key feature of national policy. The state focused on the pre-Ottoman historical period and invested in the heritage and arts sectors, viewing them as symbols of national identity. However, Iraq’s state-building journey, from the British mandate to the republic, through dictatorship, and eventually fragile democracy, led to the politicization of national heritage, sometimes turning it into a battleground for competing identities.

In the aftermath of the Gulf War in 1991, instability led to the looting of museums and libraries in southern Iraq. Thousands of artifacts flooded international markets, and the archives of the National Library and Archives Authority, as well as the Jewish Library, were transferred to the United States.

With the rise of ISIS, the erasure of cultural heritage reached its most extreme manifestation. The group destroyed hundreds of archaeological sites, libraries, and religious landmarks in an attempt to erase local identities and impose a political and cultural narrative aligned with its extremist project.

International Context: conventions and treaties for the protection of cultural heritage

As wars intensified and deliberate erasure of cultural landmarks became more common, the international community began developing legal frameworks to protect cultural property. Among the most notable are:

- The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, along with its two protocols (1954 and 1999). The convention calls for the protection and respect of cultural property, prohibits its use for military purposes, and forbids acts of retaliation against it.

- UNESCO’s 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

Types of protection provided by international agreements:

- General Protection: Requires parties to refrain from any hostile acts against cultural property.

- Special Protection: Applies to a limited number of cultural sites placed under UNESCO’s special protection.

- Enhanced Protection: Granted to cultural property of exceptional importance, provided it is formally registered.

Iraq as a Case Study in the Application of International Agreements

Despite the magnitude of its losses, Iraq has taken steps toward reclaiming its memory. In December 1994, Iraq issued an international statement calling for the enforcement of the Hague and UNESCO conventions and the return of looted heritage. It also worked to document damages and initiated bilateral negotiations with countries that had taken possession of cultural artifacts.

Iraq issued Law No. 55 of 2002 on Antiquities and Heritage, which includes provisions mandating the responsible authority to protect cultural property. It also established partnerships with international organizations to recover stolen artifacts and digitized thousands of historical documents.

As part of its broader efforts to recover its looted heritage, Iraq launched "recovery diplomacy", a coordinated initiative that unites relevant Iraqi institutions to recover lost elements of the nation’s cultural and historical identity. As of mid-August 2021, Iraq announced that it had received more than 17,000 artifacts.

Models of Resistance: libraries that refuse to surrender

In contrast to scenes of destruction and neglect, courageous cultural and intellectual initiatives have emerged, resisting the war with determination and knowledge. They held a deep belief in reading as an act of resistance, as a human refuge in times of collapse.

Muneesh Cultural Library – El Fasher

In a city besieged by military operations, surrounded by the sounds of shelling and widespread service outages, the Muneesh Cultural Library was born, a beacon of hope launched by the youth of Al-Salam neighborhood in El Fasher.

It was more than just a place for books; it was a free, open space for the community, born from the womb of war and nourished by the aspirations of readers dreaming of a different reality.

Founded during the war in El Fasher, Muneesh Library began as a grassroots, free-of-charge initiative serving the local community. Its activities were tailored to the needs of the neighborhood and the broader city, relying entirely on the voluntary efforts of local youth.

Muneesh Cultural Library. Source: Al-Jaily Ahmed

The library focused on creating a space for reading and access to books, while also organizing community events, workshops, lectures, training programs, interviews, and cultural carnivals.

These events targeted various groups in the community, especially young people, and were held inside the library building located southeast of Jisr Al-Jinan Quranic School.

After the fighting intensified and the Rapid Support Forces seized control of the southeastern part of the city in June 2024, where the library is located, on-site operations came to a halt.

However, the library’s spirit moved to the digital realm. It resumed its activities online and launched a cultural podcast that continues to carry its message of enlightenment, proving that knowledge cannot be defeated, even in the harshest of circumstances.

Experiences in Exile

In the midst of displacement, some choose exile as a platform for action, a refugee camp as a space for reading, and pain as a path toward change. For many Sudanese, exile has not merely been a forced reality, it has become a space for cultural resistance and for creating change. Here, we document real-life examples of intellectual and cultural initiatives that continued their work beyond Sudan’s borders, without ever truly leaving it. These initiatives turned knowledge into a way to heal a deep collective wound.

1. Reading for Change – Democratic Thought Project / Uganda

“Reading for Change” is one of the core initiatives of the Democratic Thought Project, which has played a major role since its founding in 2013 in promoting public awareness through reading. The program focuses on distributing a curated series of books addressing themes such as peace, democracy, development, human rights, and social justice, with the goal of building open and conscious communities.

After war broke out in Sudan, the program moved to Uganda, where thousands of Sudanese refugees now live. It began implementing its activities in camps, cities, hostels, schools, and community centers. Since September 4, 2024, over 1,800 copies of books have been printed, with 925 copies distributed to reading groups that now serve as new intellectual hubs, responding to the current crisis through peaceful means rooted in understanding, critical analysis, and collective inquiry.

One of the exhibitions of the Democratic Thought Project, which includes the Reading for Change program. Source: Democratic Thought Project website

2. Knowledge Alliance – Kampala / Uganda

The Knowledge Alliance is a cultural and social framework established in August 2024 in Kampala, initiated by a group of Sudanese professionals working in publishing, research, and cultural development. The alliance brings together 13 diverse entities, including publishing houses, research centers, knowledge initiatives, writers, and booksellers—all united around one goal: reviving a culture of knowledge in exile.

The alliance hosts a monthly public event that includes a thought forum on Sudanese and regional issues, along with a book exchange corner and the sale of books at symbolic prices, making the circulation of knowledge affordable and keeping refugees connected to critical discourse, even in the harshest of conditions.

"Mafroosh Exhibition / Kampala," organized by the Knowledge Alliance. Source: Al-Jaily Ahmed.

Conclusion

In the midst of this great destruction, libraries seem like silent losses, no one reports them on the evening news, and they don’t appear on lists of the martyrs. And yet, they die loudly within us, because they were homes of consciousness, shelters for thought, and breathing space in times of fear.

But we do not write simply to mourn, we write to resist. Just as bookshelves collapsed, knowledge initiatives rose, in the heart of war in El Fasher, and on the edges of exile. Just as books were burned in Sudan’s libraries, new ones were distributed in Kampala.

Perhaps the libraries were destroyed, but memory has not yet been defeated. As long as we read, write, and dream, there will always be a place for knowledge, and a homeland that still belongs to us.