Trigger Warning and Disclaimer: The following content includes personal and sensitive experiences. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Andariya. We encourage you to engage with the piece in whatever way feels right for you. You can read our full editorial notice here.

Historical Roots and Contemporary Transformations

Since the birth of the modern Sudanese state, hate speech has remained one of the hidden features of its public sphere. Its form changes according to political and social circumstances, but it retains its essence, deeply rooted in history. What began as a cultural legacy reflecting inequalities and multiple identities evolved over the decades into a tool of political struggle and a driver of social division.

This article examines the historical roots of hate speech in Sudan and analyzes the cultural, social, and political factors that have fueled it, in an effort to understand how this discourse was formed and why it has persisted at every critical turning point in the country’s history.

Introduction

As the current war in Sudan intensifies and social media platforms transform into unprecedented arenas of mobilization and incitement, a widespread surge of hostile rhetoric has emerged, one that invokes history, identity, and geographic belonging to justify violence and reproduce divisions. In light of this dangerous escalation of hate speech, it has become essential to return to its earliest roots in order to understand how it was formed, how it became entrenched, and how it is being leveraged today as one of the most powerful non-military weapons in the ongoing conflict.

What Is Hate Speech?

“Hate speech” refers to abusive expression that targets an individual or a group based on inherent characteristics (such as race, religion, or gender), and that may threaten social peace.

The United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech defines hate speech as “any kind of communication in speech, writing, or behavior that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of identity, namely, religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, color, descent, gender, or other identity factors.”

Hate speech is not limited to harming individuals or inciting violence against them; it constitutes an assault on diversity and human rights. It undermines social cohesion and shared values, and obstructs peace, stability, sustainable development, and the realization of human rights for all.

Hate speech can be particularly dangerous when it seeks to incite violence against specific groups. However, even in its less extreme forms, such as repeated insults, defamation, or harmful stereotypes, it can create environments charged with hostility and lead to negative consequences.

Those subjected to hate speech may experience humiliation and a persistent erosion of dignity, causing psychological harm and contributing to the further marginalization of targeted groups socially, politically, culturally, and economically.

Roots of Hate Speech in Sudan

First: The Historical and Political Dimension

Hate speech in Sudan is a phenomenon with complex roots that extend beyond the current political moment into the depths of the country’s social and colonial history. Over the course of a century, it took shape as a direct outcome of the intersections between power, identity, religion, ethnicity, and regional marginalization.

Colonial Roots of Discrimination and the Construction of “the Other”

From the early twentieth century, the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium laid the first foundations of hate speech through its “divide and rule” policy. Britain treated Sudan as two separate societies: an Arab Muslim Sudan in the north, viewed as the center of civilization and political loyalty, and an African, animist or Christian Sudan in the south and west, portrayed as a primitive space in need of “civilizing.”

These colonial policies institutionalized discrimination between centers of power and the peripheries of the state, a division that is clearly reflected today in the rhetoric of war. The same language of domination and grievance (center versus margin) that emerged more than a century ago is being revived, underscoring the profound impact of the past in shaping the contemporary landscape of hate.

An image generated using AI via the Bing Image Creator platform, inspired by the events of the war in Sudan to reflect the reality of hate speech.

In his book on Darfur and international politics, Mahmood Mamdani addresses this duality, arguing that it planted the seeds of cultural and racial superiority and reproduced them through education, administration, and language. This process turned ethnic affiliation into a criterion of social worth. With independence in 1956, the political elite inherited this value system and continued to deploy it as a tool of political domination.

The Nation-State and the Reproduction of Cultural Centralism

After independence, it was crucial to establish an inclusive project of Sudanese national identity, one that could have spared the country many crises. This point is examined in Douglas Johnson’s study on the roots of Sudan’s civil wars, which argues that the Sudanese state, after independence, reproduced cultural centralism instead of transcending it.

From the first civil war in the South (1955–1972), to the second (1983–2005), and through the conflicts in Darfur (2003–present), hate speech became a tool of political and military mobilization. Ruling elites used labels such as “traitors,” “mercenaries,” and “enemies of religion” to justify military operations against rebel or opposition groups. Conversely, some armed movements adopted counter-discourses that demonized the center and generalized responsibility for repression onto particular groups, deepening the national divide.

Alex de Waal’s analysis of war and peace policies in Sudan illustrates how hatred became an instrument of political and military mobilization from the 1960s onward. The mismanagement of diversity in the post-independence period led to the accumulation of deep grievances across wide regions, grievances that today’s war rhetoric continues to fuel. This can be seen clearly in the discourse of the warring parties, particularly the Rapid Support Forces, which use such narratives to legitimize their positions and mobilize fighters.

How Hatred was Entrenched as a State Doctrine

Successive regimes in Sudan’s post-independence history adopted ideological discourses built on binary narratives (believer versus secularist, mujahid versus agent, loyal sons of the nation versus rebels). These narratives were deployed through the media, education, and the military to inflame conflict, making religious and ethnic incitement part of the governance strategy.

Armed movements emerged as violent reactions to state practices, particularly in Darfur in the early 2000s, where mobilization relied on racial and ethnic rhetoric that included hatred toward other groups. This underscores the danger of using regional and ethnic discourse within political action. This complex reality produced ethnically composed armed groups that also served as arms of the state against rebel movements, beginning with the Border Guards, later renamed the Rapid Support Forces.

Political repression and the shrinking of public space under military regimes normalized exclusionary discourse and made regional and ethnic stereotyping an easy means of managing conflict. This is evident in the current war, where the media machinery of certain parties reproduces the same patterns of vilification, suppresses dissenting voices, and constructs narratives defining who is “patriotic” and who is not, within a media landscape engineered for that purpose. Jok Madut Jok’s work on war and slavery in Sudan similarly shows how the Islamist regime used religion and ethnicity to justify repression and expand the civil war.

This dynamic is starkly visible in the war of 15 April, where media and social platforms have been used to produce and circulate binary narratives that deepen hatred and widen the rift among citizens. Tribal and ethnic polarization has emerged as a primary response to this discourse, which frames different ethnic groups as existential enemies within clear mobilization narratives.

For example, social media platforms have witnessed a widespread campaign of polarizing messages in recent months that influence young people’s political and social decisions, demonstrating the continued impact of hate speech on everyday life. A stark contemporary example is the grave violations committed against civilians in the city of El Fasher following the Rapid Support Forces’ takeover on 26 October 2025. Reports indicate that even the elderly, women, and children were not spared, highlighting how hate speech has consistently accompanied and driven such abuses.

Post-Revolution and the War of 15 April 2023: The Return of Toxic Discourse

After the December 2018 revolution, which raised the slogans “Freedom, Peace, and Justice,” Sudan was expected to enter a new phase of tolerance and coexistence. However, with the outbreak of war between the army and the Rapid Support Forces in April 2023, hate speech returned in its most extreme forms, this time amplified through social media. Sudanese citizens themselves became instruments in a war of mutual propaganda, as racial, regional, and political discourses merged and intensified.

Understanding the dynamics of hate speech in Sudan requires examining the broader cultural context that produces and sustains it. Incendiary rhetoric does not begin solely on Facebook or TikTok; rather, it reproduces and reactivates linguistic and symbolic frameworks deeply embedded in collective memory and historical narratives. Confronting this phenomenon therefore requires a profound cultural reading of Sudan’s social structure before any legal measures can be effective.

Terms carrying regional and racial connotations became embedded in everyday language, not merely as descriptors, but as tools for constructing “the other” and stripping them of humanity. With the spread of modern media, the amplification of these terms accelerated, and their political instrumentalization intensified.

Sudanese arts, music, poetry, and theater, represent a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they have historically played important roles in civic expression and resistance to authoritarianism. On the other, in the current conflict they can be used as tools of mass mobilization and incitement. Simple slogans or musical clips can become engines of emotional agitation, reflecting both the sensitivity of Sudan’s cultural landscape and the speed with which it can be politically exploited.

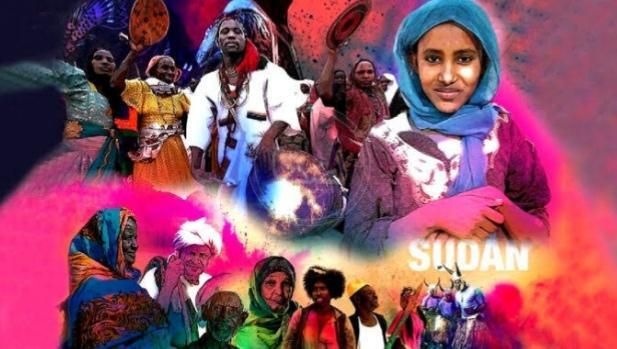

An image reflecting the cultural diversity in Sudan. Source: Sudan Magazine.

Everyday language and popular proverbs have played a significant role in normalizing hate. Phrases that may be used in daily life jokingly or descriptively can, in moments of conflict, turn into tools of classification and incitement. In a society rooted in oral tradition, these words easily migrate to social media, where they are recycled in the form of videos or satirical images, expanding their reach and becoming instruments for justifying violence. This includes mocking women or the customs of certain groups, using descriptions that undermine dignity and honor, as well as regional labeling, such as proverbs that imply “those who come from a certain geography bring no good.”

Conversely, figures known as hakamat (traditional women poets and singers) have produced hate-laden descriptions targeting other groups. Through chant-like, mobilizing language, they have encouraged degrading behaviors and justified them using a repertoire of proverbs and expressions that similarly demean the dignity of women and members of other communities. These expressions are well known and need not be cited explicitly here. Historically, individuals have been driven to engage in fighting and revenge simply to have their names praised in the chants of the hakamat as brave, or to avoid being labeled cowards if they failed to retaliate.

Cultural symbols and myths are also exploited to legitimize hostile discourse. Invoking historical figures or ancient heroic narratives creates the impression that the conflict is not temporary, but rather a battle for cultural survival. This symbolic use is not limited to political rhetoric; it extends to songs, slogans, and folk stories that are distorted and repurposed to serve immediate agendas, becoming emotional ammunition that pushes audiences toward fanaticism. Distorted artistic products have emerged, in comedy and exclusionary or racist songs alike, that glorify killing and degrade the dignity of ethnic groups through overtly racist language.

The African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS, 2021) noted that discrimination and hate speech in Sudan are not merely reflections of political crisis, but part of a prevailing culture that employs the language of “stigmatization” against specific groups, particularly in armed conflicts in Darfur and the Nuba Mountains. This makes the cultural dimension of hate speech especially dangerous, as it shifts from being a media discourse to a social practice that legitimizes violence and justifies exclusion.

In sum, the cultural dimension of hate speech in Sudan goes beyond the current political moment and reflects a deeper crisis. This discourse draws on long-standing cultural narratives that reproduce division. Confronting it therefore requires a comprehensive approach that restores shared cultural values and strikes a balance between freedom of expression and protecting society from sliding into violence legitimized by words.

The Explosion with the April 2023 War

The outbreak of the April 15 war ignited the seeds of hate speech. Social media platforms such as Facebook and X turned into parallel battlefields. Videos and statements by military and political leaders circulated widely, carrying collective accusations and incitement against specific regions or tribes. Hate speech thus became an integral tool of war, used to inflame violence, demonize opponents, and justify violations.

The conflict created a security and media vacuum that various actors exploited to spread messages of hatred and incitement, whether through traditional outlets or digital platforms. This shift turned the war itself into fertile ground for reproducing old stereotypes and social divisions in sharper, more organized forms.

War can begin with a word. Source: Al-Sayha Newspaper

Conversely, a paper by Fawzi Ahmed Abdallah Salloum (ResearchGate, 2025) emphasizes that Sudanese culture is not merely a stage for hate speech, but also contains alternative resources to confront it. These include values of tolerance embedded in traditional customs, as well as the role of oral storytelling and folk arts in promoting coexistence. However, these resources have weakened in the face of the dominance of inciting discourse amplified by digital and media platforms.

The significance of these proverbs and popular symbols lies in the fact that they do not merely reflect old perceptions; they are now being directly used on social media platforms to fuel regional polarization. Many pages recycle these expressions in the context of war, giving them new life and transforming them from oral heritage into tools of incitement and mobilization. This has made popular culture one of the most important incubators reproducing hate speech in Sudan.

Historical Sudanese Practices in Conflict Management

Because hate speech cannot be confronted solely through laws or technical tools, but also through living cultural resources, it is essential to recall certain Sudanese practices that historically played a pivotal role in de-escalation. Traditional customs such as tribal reconciliation and the rituals of judiyya (community mediation) have contributed to containing conflicts and repairing social bonds, even during the most turbulent periods.

Practices like judiyya and tribal reconciliation councils formed effective social frameworks for managing disputes and easing tensions across multiple historical moments. Judiyya relies on the intervention of ajawid, respected community elders known for neutrality and broad acceptance, who convene mediation sessions grounded in customs and social ties. These processes usually conclude with written or verbal agreements that include pledges, compensation (diya), and symbolic actions confirming the end of the conflict.

Such practices played a major role in containing disputes in Darfur, Kordofan, and eastern Sudan, particularly over resources such as land, grazing areas, and water. Anthropological research shows that judiyya, alongside tribal reconciliation rituals and spiritual mediation through Sufi orders, functioned as an unwritten social law that preserved community cohesion even in periods of extreme instability.

Folk Arts and the Construction of a Shared Collective Consciousness

Oral storytelling and folk arts represent a central resource in this context. Sudanese proverbs carry clear messages about coexistence, wisdom, and avoiding discord, such as the well-known saying that urges restraint and foresight: “He who vents his resentment destroys his own city.” Folk songs and popular theater likewise invoke values of cooperation and human connection that transcend divisions.

Ibrahim al-Kashif’s song “I Am African – I Am Sudanese” stands as an early example of national music reinforcing a shared identity and affirming the unity of Sudanese destiny. The songs of Mohamed Wardi, such as “Ya Sha‘ban Lahabak Thawretak” (“Oh People, Your Revolution is a flame”), call for collective resilience and resistance. Today, Sudan is in dire need of songs that summon solidarity for a wounded homeland, such as “Our country, let us raise its status… Sudan has called us, solve the problem without the sound of a gun; my brother, stand with me, not against me.”

The Nafeer tradition also stands out as one of the most important social practices embodying practical cooperation. In Nafeer, community members come together to help an individual or family with farming, construction, or emergencies, accompanied by collective singing that encourages participation and solidarity. An iconic example is Hamad al-Rayeh’s song composed during the Nile floods on Tuti Island: “I admired them today when they came and built the embankments… I admired the sons of the community; they impressed me and gladdened my heart.”

In theater, Sudanese productions have played an effective role in addressing social issues and reinforcing values of unity. The play Tajouj, drawing on folk heritage, highlights the power of storytelling in uniting the cultural memory of diverse groups. Meanwhile, productions by the Friends Theatre Group, such as “Suheir's Engagement”, tackled issues of social acceptance and coexistence across classes and families. Works like “Stories and Memories from the History of Sudanese Theatre” document the evolution of the theatrical movement and its role in building a collective consciousness rooted in participation and human connection.

Notably, there are also digital and educational initiatives such as Wiki Sudan, one of the most prominent youth-led digital efforts to document heritage. The initiative focuses on collecting folk songs, oral arts, and cultural practices from across the country and re-presenting them in clear, accessible language for young audiences. This project represents a model of positive discourse that highlights Sudanese diversity and counters inciting narratives based on distorting identity and shared values.

Similarly, the Hakama platform produces visual and written content that showcases heritage stories. Alongside folktales and popular proverbs, such initiatives aim to reintroduce these cultural resources to young people as part of an effort to build an alternative discourse that can compete with rapidly spreading inciting narratives. These examples demonstrate that cultural tools are not merely supplementary to efforts against hate speech; they are a core component of society’s capacity to rebuild trust and create spaces for positive, constructive communication.

Art as a Catalyst

The long-term effects of hate speech on Sudan’s cultural and social fabric are extremely serious. The exploitation of symbols, songs, and proverbs for incitement pollutes the shared cultural reservoir that forms the foundation of trust and coexistence. When cultural language shifts from a tool of communication to an instrument of exclusion, building reconciliation becomes far more difficult and requires the long-term reconstruction of alternative narratives.

Confronting hate speech in Sudan from a cultural perspective therefore requires a set of interlinked interventions:

- Re-narrating national history through multiple voices that emphasize convergence rather than exclusion. This includes civil and cultural initiatives that emerged during the war and seek to re-present the national narrative from diverse angles, such as Al-Tareeq 18 (Route 18), a platform that showcases different stories and viewpoints. Groups of intellectuals and activists have also organized dialogue circles bringing together participants from Darfur, Khartoum, Kordofan, and eastern Sudan to discuss their experiences of war, identity, and coexistence, such as those facilitated by the Youth Rights Movement. These dialogues have enabled the emergence of alternative narratives that counter exclusion and have reaffirmed the deep historical interconnectedness of Sudanese society as a basis for cohesion rather than division.

- Integrating educational approaches that expose the harmful use of popular language. Youth- and journalist-led initiatives have worked to raise media and linguistic awareness, such as Beam Reports, through fact-checking and analysis of popular discourse, particularly language used for incitement and rumor-spreading. Targeting young audiences, these programs explain how everyday expressions can be weaponized to fuel hatred, making non-formal education an effective first line of defense against language that ignites social violence.

- Supporting the arts that promote coexistence and tolerance. Despite the brutality of war, Sudanese art has remained a space of resistance that expresses and defends coexistence. Independent artistic groups have launched digital documentary exhibitions and collaborative works bringing together displaced people from different regions, such as the Sudanese Art Archive, affirming that culture can rebuild what war destroys and that art remains a powerful counter-voice to hatred.

- Creating dialogue platforms linking inside Sudan and the diaspora. As displacement and migration expand, virtual dialogue platforms have emerged bringing together activists, academics, and researchers from inside and outside the country. The Advocacy Group for Peace (AGPS) launched the Sudan Peace Call initiative to end the war and build sustainable peace. These platforms discuss the roots of the conflict and the impact of hate speech, while offering joint statements and alternative visions for reconciliation and social reconstruction. This cross-geographical communication has helped reconnect what war severed and contributed to building a collective awareness that lays a new foundation for national dialogue.

- Developing local verification mechanisms in Sudanese dialects to counter rumors and inciting discourse. Initiatives such as "Nuuar media" work to promote a culture of peace by documenting harmful content, analyzing its implications, and warning communities of its dangers. These efforts are particularly important because they rely on deep local contextual knowledge, making them more effective at dismantling hate speech and preventing its escalation into physical violence.

This cultural approach can play an effective role in countering hate speech and advancing coexistence and social peace. What circulates on digital platforms today is no longer a fleeting exchange; hate speech in Sudan has become part of lived reality, reshaping relationships between communities and affecting daily life in besieged cities, displacement corridors, and exile. In this critical moment, the reader’s responsibility is clear and immediate: pause before sharing, verify the source, and ask whether the content reduces tension or fuels it. In such an inflamed context, even a simple individual act, such as refraining from sharing inciting content, can be a small but meaningful step toward protecting what remains of trust among people.

In Part Two below, we will delve into the contemporary face of hate speech, how words have been transformed into weapons, and how they might yet reclaim their role as bridges for peace and coexistence.

How Words Became Weapons (2-2)

Manifestations of Hate Speech in the Sudanese War

This section examines the manifestations of hate speech in Sudan and how hostile language has seeped into the details of everyday life since the outbreak of the most recent war. From battlefields to social media platforms, and amid both attempts to confront this discourse and initiatives to promote peace, a fundamental question emerges: how can the same word shift from being a tool of division to becoming a bridge for understanding?

Introduction

Hate speech accompanying the current war can be classified into several main patterns, most notably: demonization discourse, which turns the opponent into something non-human; threat discourse, which justifies violence against specific groups; disinformation discourse, based on the spread of rumors; and identity-based discourse, which reproduces regional and ethnic divisions. These classifications help analyze how such discourse circulates within society and how it shapes public opinion.

Since April 15, 2023, hate speech has taken multiple forms that go beyond theory into tangible reality, becoming observable in everyday life as well as in media and political spheres. The most prominent manifestations can be summarized and analyzed as follows:

Demonization of Ethnic and Regional Groups

Amid the current war, the demonization of ethnic and regional groups has emerged as one of the most dangerous forms of hate speech threatening national unity and social cohesion. Since the outbreak of fighting in April 2023, hostile rhetoric has spread portraying certain social components as “enemies of the state” or “traitors,” reproducing narratives rooted in political and cultural systems that have operated for decades. These narratives reduce peripheral groups to stereotypes that exclude them from the national sphere and strip them of full citizenship.

Social media has played a multiplying role in amplifying this discourse during the war. Human Rights Watch documented dozens of images, videos, and posts across digital platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, and X that promote narratives justifying violence against specific groups.

According to Amnesty International’s 2024 report, the escalation of regional and ethnic hatred in Sudan has created fertile ground for grave violations against civilians, particularly in areas experiencing ethnically charged fighting. The report noted that hate speech has become a tool for combat mobilization, not merely a form of political expression, making it extremely difficult to contain in the absence of independent legal and media institutions.

Justifying Violence and Revenge

The discourse justifying violence intersects with demonization in structure and motivation, but surpasses it in impact, as it transforms killing and destruction into “legitimate” reactions framed as revenge or the restoration of dignity. From the early months of the war, narratives spread portraying violations against civilians as “just punishment” or “delayed reckoning” for past grievances, giving violence a false moral cover and rendering it socially acceptable in some circles.

This discourse fuels a mindset of collective revenge and undermines the very idea of justice and accountability, portraying violations as a national duty. It reproduces the logic of the Darfur civil war in the early 2000s, when incitement became a tool for collective punishment against specific ethnic groups. Today, the same pattern is repeated in both field and political discourse, where looting, extrajudicial killings, and forced displacement are justified based on regional allegiance or political stance.

Alarmingly, revenge discourse in Sudan is not limited to justifying armed actions; it extends into media narratives that frame the war as “purification” or a “correction of the state’s path.” This entrenches violence as a political alternative to dialogue and threatens future reconciliation by planting seeds of hatred across generations.

Targeting Women Through Exclusionary and Sexualized Discourse

Another prominent manifestation is the systematic use of sexualized and morally stigmatizing discourse against women from certain groups. Women have been portrayed either as “spoils of war” or as “tools of betrayal,” contributing to the normalization of sexual violence as a weapon of conflict and introducing new dimensions of hate speech intersecting with gender.

An article published by All Africa in July 2025 on hate speech against women in Sudan documented how digital platforms were used to launch campaigns of defamation, mockery, and threats targeting female activists. Women faced widespread smear campaigns, reputational attacks, and threats, demonstrating that hate speech extended beyond ethnic and political dimensions to include gender.

Media reports further indicate that female journalists and media activists were subjected to threats, harassment, and assaults during coverage, in addition to defamation campaigns linked to their documentation of war crimes. This has exposed women to compounded forms of violence during the conflict. The phenomenon is not isolated, but affects many women leaders in Sudan amid the rise of misogynistic hate speech that weaponizes “honor” and identity as tools of exclusion.

The tangible manifestations of hate speech in the Sudanese war reveal that it has not been merely rhetorical, but rather a comprehensive and operational system. What is new is that this discourse has moved beyond political elites into popular and digital spaces, making ordinary citizens active participants in its production and dissemination. This popularization of hatred makes responses more difficult, as it requires a balanced, multi-layered intervention involving media, education, religious discourse, and civil initiatives together.

Social Media and Hate Speech

With the outbreak of the Sudanese war, the digital space has turned into a new battlefield no less dangerous than the front lines. Social media platforms have become the most influential arenas for shaping public opinion and constructing competing narratives. They have been used both as tools for mobilizing supporters and inciting violence against opponents, and, at the same time, as spaces for searching for alternatives that call for coexistence and peace.

Digital discourse has not been merely spontaneous interaction; rather, it has been deployed in an organized and calculated manner. The warring parties injected their narratives through thousands of influential accounts, relying on visual spectacle and emotionally shocking content, images and videos, to generate psychological mobilization and prepare the ground for justifying violence. This massive flow of information fueled polarization and produced “echo chambers” that trap users within a single narrative circle, making them more susceptible to adopting extreme and hostile positions.

At the same time, the scene has not been devoid of counter-efforts. Youth initiatives and civil society organizations have worked to spread alternative messages promoting tolerance and unity, while fact-checking efforts emerged to curb the spread of disinformation. Some activists turned to art, music, and personal storytelling as softer tools to influence public sentiment and rebuild trust among different groups. However, these efforts have faced significant obstacles, including weak digital infrastructure, the dominance of sensational content in platform algorithms, and security threats targeting activists.

Political and Social Repercussions of Hate Speech

Since the outbreak of the war, hate speech in Sudan has shifted from being merely an inciting linguistic phenomenon to a structural factor that profoundly reshapes social and political relations. Systematic waves of incitement have eroded social trust, turning tribal or regional affiliation into a primary criterion for determining loyalty or hostility. This has led to the collapse of local solidarity networks and traditional neighborhood ties that once formed the backbone of social cohesion.

This breakdown has made communities more vulnerable to political manipulation and weakened the capacity of civil initiatives to build peace or mediate between conflicting parties. According to the Conflict Sensitivity Facility report on hate speech in Sudan, hostile discourse has become a key driver of the continuation of conflict and forced displacement.

Fragmentation of the Social Fabric and Loss of Mutual Trust

Hate speech has created a state of constant suspicion among ethnic and regional groups, where the “other” is no longer seen as a partner in the nation but as an existential enemy. This shift has struck at the core foundation of coexistence: trust. As a result, relations between individuals and groups are now governed by fear and doubt, threatening prospects for post-war social reconciliation.

This division is particularly dangerous for younger generations. Bridges of trust among youth themselves have eroded. The digital space, once expected to foster communication and creativity, has turned into a field of accusation, where collective identity gives way to narrow affiliations. As a result, the spirit of initiative weakens and the space for hope in coexistence shrinks.

Incendiary discourse has also contributed to the erosion of civil and political capital. Local institutions and intermediary organizations have lost credibility after being accused of bias or collaboration, leading to a withdrawal of popular support. This vacuum has been filled by militias and armed actors. With the weakening of the central state, these non-state forces have imposed alternative forms of governance and justice based on tribal or regional loyalty rather than citizenship. Human Rights Watch’s analysis of ethnic violence in Darfur highlights how campaigns of ethnic targeting were accompanied by systematic mass displacement.

At the same time, hate speech has contributed to forced demographic engineering through mass displacement, altering the population composition of entire areas along ethnic or regional lines. This shift was not merely a byproduct of war, but was wrapped in mobilizing narratives of “social cleansing” or “reclaiming land,” as documented by Amnesty International, which noted that identity and gender-based violence became tools for redrawing social maps.

Psychological and Social Impact of Hate Speech

Psychologically, this discourse produces a persistent sense of fear and insecurity. Many young people live in a constant state of tension, afraid to express their opinions or even their accents. Some withdraw entirely from public life, while others adopt aggressive counter-discourse as a form of self-defense. This cycle of fear and reaction creates a psychologically exhausted, hyper-vigilant generation with little trust in the future.

Hate speech has also left a legacy of shame and social stigma, particularly among women and direct survivors of sexual violence or symbolic humiliation. This stigma leads to social isolation and prevents victims from seeking justice or treatment, reinforcing a cycle of silence and impunity. Amnesty International’s report on sexual violence in Sudan confirmed that hundreds of women refrained from reporting abuses out of fear of social retaliation.

Politically, hate speech has become a tool for justifying violence and revenge within official and semi-official discourse, where collective punitive practices are framed as “legitimate defense” or “cleansing of collaborators.” Such political instrumentalization undermines any path toward democratic transition or national reconciliation. Statements from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights have warned of the rise of retaliatory rhetoric and its impact on obstructing international mediation efforts.

This reality entrenches a culture of impunity, granting non-state actors social and political cover to commit violence without accountability under the pretext of defending the group or “tribal honor.” With the collapse of judicial institutions, public belief that justice will be served continues to erode, pushing some groups toward self-administered revenge and further deepening the cycle of violence. The African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies has documented these practices in its reports, confirming that impunity has become a systemic feature of conflict zones.

Within the Sudanese diaspora, hate speech has expanded across digital platforms, where sarcasm and mocking language have become tools for reproducing division and sustaining polarization among migrants and displaced communities. This dynamic has negatively affected even humanitarian and political support campaigns. Verbal hostility abroad feeds hate fronts inside Sudan, further complicating reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts.

It can be argued that hate speech in Sudan has moved beyond mere verbal expression to become an integrated system that both produces and reproduces violence. A 2025 study by the Norwegian Centre for Peace Studies showed that since the outbreak of the conflict in April 2023, social media platforms have functioned as a parallel battlefield, where algorithms amplify incendiary messages, images, videos, and rumors that inflame ethnic and social divisions. Media analyses also indicate that some diaspora circles have exploited ethnic and regional identities to fuel the conflict, intensifying hostility and reproducing internal divisions within Sudan.

Accordingly, hate speech is no longer just satire or harsh criticism; it has evolved into a digital system that fuels conflict, legitimizes ethnic and racial discrimination, and turns verbal antagonism abroad into direct triggers for violence at home. This development complicates peace and reconciliation efforts and weakens the international community’s response to Sudan’s humanitarian and political crises.

Addressing hate speech therefore cannot be limited to media regulation or awareness campaigns alone; it requires comprehensive institutional reform encompassing the judiciary, media, education, and curricula, with countering hate speech integrated as a core component of any peace agreement or political transition. The United Nations has repeatedly emphasized the need to embed hate speech prevention within peacebuilding and civilian protection processes.

Erosion of State Legitimacy and Institutional Fragmentation

The impact of hate speech has not been confined to psychological or symbolic harm; it has directly affected the social fabric and the unity of the state itself. By entrenching ethnic and regional divisions and deepening mistrust among social groups, hate speech has weakened prospects for dialogue and reconciliation, making peaceful solutions increasingly difficult. In this way, words have shifted from being tools of expression to instruments of social fragmentation and prolonged war.

When political or military actors engage in producing hate speech, public trust in the neutrality of the state and its institutions collapses. This leads to the emergence of alternative loyalties, regional, tribal, or militia-based, which become the primary reference points for citizens. Such fragmentation of legitimacy not only opens the door to chaos but also complicates any effort to rebuild the state. The social and political consequences of hate speech in Sudan are evident in the disintegration of social cohesion, the collapse of trust in state institutions, and the reproduction of violence in a continuous cycle. These are not short-term effects, but long-lasting consequences that will obstruct any peace project unless they are addressed through comprehensive policies that restore trust, rebuild legitimacy, and break the cycle of revenge.

Documented Cases: How Words Became a Weapon

Field evidence consistently demonstrates that hate speech in Sudan has not remained merely rhetorical. In many cases, it has become a logical component of a sequence of actions leading to mass killings, organized displacement, and the deliberate obstruction of humanitarian aid. The following are selected cases illustrating the mechanisms through which speech translates into violence.

Attacks on Camps and Shelter Sites

Subsequent reports have documented attacks on displacement camps and shelter centers, including deadly operations in Darfur that resulted in the killing of civilians and humanitarian workers and the disruption of essential services. The attack on Zamzam Camp in North Darfur (April 2025) stands as a recent example of how distorted narratives and manipulated imagery were used to justify assaults on sites protecting civilians, leading to dozens of deaths and the obstruction of humanitarian access.

Such operations demonstrate that hate speech functions to strip certain groups of their “protected civilian” status, thereby undermining humanitarian response. Targeting protection sites amplifies civilian suffering and transforms shelters from safe havens into military targets, an immediate, tangible consequence that reveals hate speech as a tool for disabling humanitarian protection.

For further documentation, see the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights report dated 5 September 2025, which records arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial executions, and unlawful detention in Khartoum, noting that these violations were linked to intensive social media campaigns that provided discursive cover for crimes.

In urban environments, digital rumors are exploited to short-circuit justice mechanisms; attacks on individuals or groups may begin with an online post and conclude with a locally sanctioned killing, reflecting the power of hate speech to shut down legal processes. Some local media figures have used framing that justifies violence against specific political and tribal groups, resulting in widespread social isolation, the normalization of revenge, and physical assaults on civilians. According to a Human Rights Watch report from 2025, more than 120 cases of direct incitement were documented in local media outlets.

A clear example of the intersection between rhetoric and violence occurred during military operations in El Fasher, where clashes were accompanied by a surge of inflammatory voice messages and videos targeting specific communities as alleged supporters of the opposing side. This rhetoric heightened aggression among some fighters and expanded the scope of abuses against civilians, illustrating how words can function as direct fuel for battlefield violence.

An AI generated image via the Bing Image Creator platform, illustrating the impact of words and violent rhetoric in the Sudan war.

The most dangerous legacy that hate speech leaves on this generation is not the immediate wound, but the normalization of violence within the collective consciousness. When young people become accustomed to the language of exclusion, they gradually lose their sensitivity to injustice, and conflict becomes part of everyday life.

Protecting this generation therefore begins with restoring the humane meaning of words, and with equipping young people with critical thinking skills, psychosocial support, and opportunities that open windows to the future instead of the walls that surround them. Yet, despite this bleak landscape, there are still real opportunities for rebuilding.

How can hate speech be confronted?

Despite the seriousness of hate speech, confronting it remains possible if political and social will exists. The challenges lie in weak legislation, the absence of effective oversight mechanisms, and the exploitation of inciting rhetoric by some political elites as a means of retaining power. Opportunities, however, lie in the role of civil society organizations, professional media, and youth initiatives in promoting a culture of peace and tolerance. These efforts require a strong institutional framework and clear media policies to ensure that words are transformed from tools of destruction into tools for building a shared future.

Initiatives to counter hate speech

Amid Sudan’s ongoing crisis, several local initiatives have emerged to combat hate speech and promote peaceful coexistence among Sudan’s diverse communities. Among these initiatives:

One youth-led initiative focused on training and capacity-building offered an inspiring model for confronting hate speech through workshops held in 'Almarai', sans-serif !important last October. The initiative brought together young people from diverse intellectual and cultural backgrounds and, over two days, transformed this diversity into a shared strength with a clear vision: promoting a culture of peace and launching local initiatives to restore social trust at a critical moment in Sudan’s history.

The workshops relied on interactive methods and direct discussions about the roots of verbal violence and hate speech in the public sphere, resulting in the formation of a symbolic youth network called “Pulse of Peace,” reflecting ongoing communication and readiness for collective action. This experience shows that confronting hate speech is not limited to condemning it; it requires creating genuine spaces for dialogue that enable young people to craft alternative narratives based on understanding, coexistence, and a future free from division.

In September 2025, UNESCO’s office in Sudan implemented a training workshop in Port Sudan titled “Ethical Journalism in Times of Crisis: Tools to Combat Hate Speech.” The workshop brought together Sudanese journalists from various print, radio, and television institutions, focusing on providing practical skills and effective strategies to curb hate speech and media disinformation, particularly under wartime conditions and a complex media landscape.

Through applied training and open discussions on responsible conflict reporting, the workshop helped deepen understanding of the ethical role of media in protecting social cohesion and promoting discourse that rejects incitement and verbal violence. Such initiatives are an important step toward strengthening professionalism in Sudanese media, balancing truth-telling with the responsibility to avoid incitement. Media can build peace just as easily as it can deepen divisions when professional ethics are absent. By training journalists in verification and responsible storytelling, these initiatives can enhance the quality and integrity of media content as a tool for awareness and peace.

Additionally, a local community development organization organized a series of awareness sessions in Nyala, South Darfur, targeting youth and women as part of a project aimed at strengthening their capacity to contribute to peacebuilding. The initiative focused on raising awareness of the dangers of hate speech and its role in fueling local conflicts, encouraging participants to adopt language of tolerance and coexistence within their communities.

These efforts underscore the importance of extending anti–hate speech initiatives beyond urban centers to more fragile areas, where verbal violence intersects with social division and displacement. They also highlight the role of youth and women as key actors in promoting social peace, as such initiatives provide them with intellectual and community tools to transform dialogue from a space of tension into a platform for understanding. This experience confirms that confronting hate begins from the grassroots, from within neighborhoods striving to chart a path toward peace despite the scars of war.

These initiatives demonstrate that Sudanese society, despite ongoing war and immense challenges, continues to seek ways to counter hate speech and promote peaceful coexistence. In Darfur, for example, some community initiatives have launched programs bringing together young people and women from rival groups to exchange dialogue and understanding, helping to ease local tensions and rebuild trust.

Experiences in countries such as South Sudan and Ethiopia also show that similar initiatives can enhance the capacity of conflict-affected communities to shift from division toward civic cooperation, confirming that local and international support can contribute to tangible progress toward a more unified and cohesive Sudanese society despite the impacts of war.

Current challenges:

- Weak laws and institutional mechanisms for monitoring digital media discourse.

- Absence of media literacy education in schools and universities.

- Politicization of media platforms and lack of professional standards.

- Low psychological and social awareness of the power of words as drivers of conflict.

Opportunities and recommendations:

Despite the harsh reality, there are real opportunities to redirect public discourse toward recovery:

- Develop a comprehensive strategy across education, media, politics, and civil society.

- Activate digital media literacy in education systems and youth programs.

- Launch social campaigns that counter hate.

- Enact clear laws criminalizing incitement to violence and hate speech.

- Establish an independent commission to monitor content and protect society from systematic disinformation and incitement.

- Support initiatives that promote alternative narratives grounded in coexistence and mutual respect.

- Rebuild trust among different social groups, especially those affected by conflict.

Sudan’s recent war has proven that words can be deadlier than weapons: while a bullet kills one body, hate speech can kill the spirit of an entire society. Confronting this phenomenon is not solely the responsibility of institutions; it is a collective duty that begins with individuals and their everyday language, and extends to media, politics, and culture.

Building a new Sudan grounded in peace, freedom, and justice requires dismantling the linguistic and cultural structures that have fueled hatred for decades and replacing them with an inclusive human-centered discourse that restores citizenship, dignity, and justice to their rightful place.