Editor's Note: we are thrilled to introduce our upcoming book: (UN)DOING RESISTANCE: Authoritarianism and Attacks on the Arts in Sudan’s 30 Years of Islamist Rule, written by Ruba El Melik and Reem Abbas. Below is the introduction chapter to give you a preview of the book. The book launch will be held at Andariya Park in Manshiya. Follow our social media pages @AndariyaMag to learn more and sign up for the event.

**

When Art is Shutdown: Exploring the Contemporary Impact of the Crackdown on Art Between 1989 to 1994.

In December 2018, protests erupted in Sudan against the Islamist ruling party, the National Congress Party (NCP), and they quickly evolved into a nation-wide revolution that saw organic grassroots mobilization until the fall of the regime in April 2019, two months before the thirty-year anniversary of the coup that brought the Islamists to power. The revolution, which lasted four months and dragged on until the formation of the transitional government in August 2019, was evidently fueled by art in all of its manifestations. Rappers and traditional musicians produced songs that inspired the protesters and were used by them as slogans for the protests and marches, while graffiti artists spread information and documented the protest movement through their murals and street artwork.

Every statement that was written by the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), a body of professional trade unions that instigated and organized all protests until the fall down of the government, was intertwined with poetry and meticulous writing. The statements celebrated nationalist songs and integrated revolutionary and resistance poetry, and this further galvanized people to protest. When the SPA was criticized for their use of classical Arabic and elitist language, the SPA began spreading statements written in Randook, which is the colloquial language of the streets and has origins in the peripheries of Khartoum. Artists found themselves at the center of the movement as many canceled new years parties in solidarity with the protest movement and to mourn the lives lost. When they did perform, they would sneak anti-government slogans into their lyrics.

In April 2019, when millions marched to the headquarters of the military in Khartoum and to the military buildings in other cities, the march was transformed into a sit-in that continued for two months and became Sudan’s largest arts festival. Artists painted most walls in the area and expanded their work to paint revolutionary murals in different neighborhoods while musicians held their largest concerts at the sit-in. Poets performed, theatre shows were set up, and documentaries that were once banned inside the country were screened. The art produced during the revolution went viral, as it was covered by foreign journalists who swarmed Khartoum to report on the revolution. However, the narrative was always lacking the historical significance of how art was mobilized.

In our effort to understand the nature and the history of how revolutionary art was developed, it is critical to look at Sudan’s contemporary history. Art in Sudan was nurtured by its many revolutions; in 1964, in 1985, and in 2018/2019. However, due to the military dictatorships that continued to rule Sudan since independence except for brief honeymoons of democracy, art was always positioned as a revolutionary product. It was positioned as a product of resistance and defiance to the dictatorships, and a celebration of freedom and the struggle of the people.

To contextualize the revolutionary art produced and consumed during the 2018 revolution, we look at Sudan’s contemporary history by briefly looking at the politically turbulent 1980s and deeply looking at how culture and art were policed in the dark 1990s, which is the period after the Islamists took over power through the 1989 coup. During that period, the entire artistic and cultural landscape came under attack as artists were arrested, sacked from jobs, and intimidated, but the infrastructure that has always supported this landscape suffered the most as the book hopes to explain.

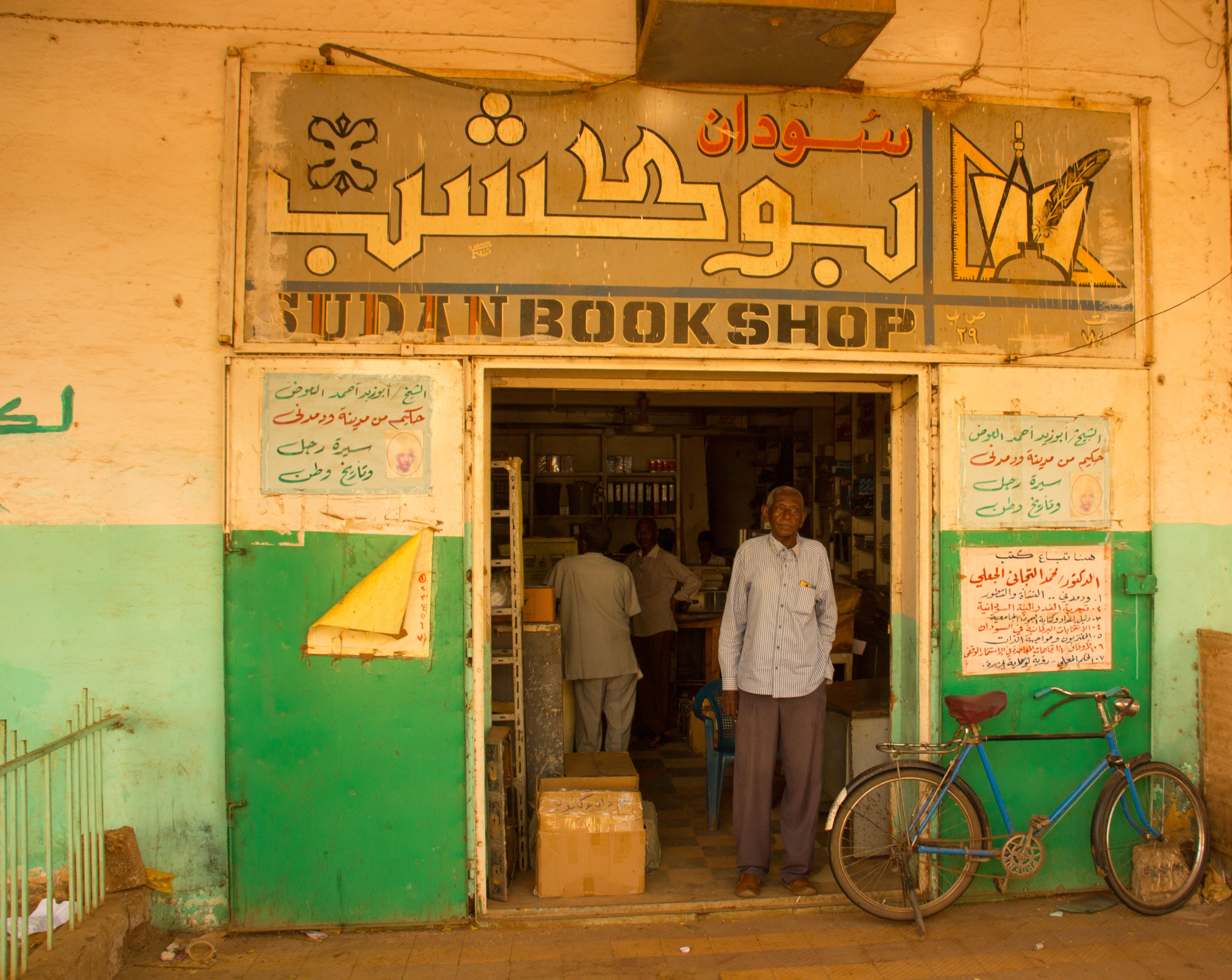

Bookshop in Madani. Credit: Andariya

Art Landscape in the 1980s

The 1980s was a chaotic decade that defined much of Sudan’s contemporary history. In 1969, Gaafar Al-Nimeri, a young leftist military officer staged a coup d’etat supported by a faction within the Sudanese Communist Party (SCP). He quickly fell out with the communists and executed the crème de la crème of the SCP, 12 members of its first-row leadership, in July 1971, but nonetheless, his leadership continued to push through leftist ideas.

Nimeri continues to be a point of contention for intellectuals who disdain him as a dictator, but also appreciate him for providing state funds to enrich art in Sudan. From the onset, Nimeri brought on technocrats and cultural figures in the different state institutions, such as Ali Al-Mak, Mohamed AbdelHai, and others who were employed in the state cultural institution known as Maslahat Al-Thaqafa. In Nimeri’s Sudan, intellectuals were integrated within the civil service.

The state funded a cultural festival and events and Nimeri made a point of including a jazz band called the Blue Stars in his foreign visits and upon reaching their respective destinations, they would hold concerts to promote Sudan’s music. Another means used by Nimeri was to integrate art into party politics. The Mayo regime, as it was known, had its own cultural platforms, a musical band, and songs that were distributed and broadcast nationwide. Additionally, culture was also at the heart of politics for the regime and was particularly referenced in 1972 in the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement which ended Sudan’s first civil war. The Anyanya group, which viewed itself as a liberation movement that had taken up arms against the central government from the 1950s, viewed culture as a point of disagreement as they wanted the government to respect and advance a diverse cultural policy that respects the religious and cultural differences in Sudan, as opposed to only advancing Arab-Islamic culture.

In September 1983, Nimeri announced the introduction of the “Origins of Jurisprudence Act” which came to be known as the September laws or Shariah laws. The country’s policy shifted from a liberal one to one that promotes Shariah and implements Huddud. A combination of repression, the re-instigation of the conflict in South Sudan and the unpopular September laws brought down the government of Nimeri in the 1985 April/May Intifada.

After a year-long transitional rule by the military general Abdelrahman Sawar Al-Dahab, general elections brought Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi to power in 1986 and parliamentary democracy was duly instituted. The post-intifada period between 1985 to 1989 was a period of rich artistic production. The Sudanese Writers Union opened its doors in 1985 and that period saw the emergence of many singers such as Mustafa Sid-Ahmd, Amal Al-Nour and others. All the cinema houses would play revolutionary songs before the screening of films.

The Crackdown: 1989 to 1996

The coalition government that was elected in 1986 was, unfortunately, weak and fractured. In fact, “the fragile partnerships broke up twice within three months in 1987, and Sudan was technical without a government for almost a year.” Economic deterioration with serious political instability caused by various “unworkable” coalitions within the government led to frustration and this meant that when the 1989 coup d’etat by the Islamists happened, it was painted as the wish of the people and the Islamists called their coup the “national salvation revolution”. In fact, the Islamists were already controlling important portfolios in the post-revolution government and ensured that the September laws, which caused an uproar in 1983, remained in place.

In fact, the only real attempt to repeal the September laws happened on the morning of June 30th, 1989 when “a committee of senior lawyers, including former chief justices, a former Minister of Justice, and several senior advocates presented to the government a draft repealing laws that, if accepted, would have brought about the final abrogation of the September 1983 laws” (Warburg 1990: 636).

On the night of June 30th, the 1989 coup took place and its orchestrators, young military soldiers under the influence of the godfather of the Islamist movement, Dr. Hassan Al-Turabi, a French educated lawyer and one of the backbones of the Islamic movement in Sudan introduced a military body calling itself the Revolution Command Council that was set to govern the country.

In its first few days in power, it dissolved Al-Mahdi’s government, abolished all political parties, banned independent newspapers, dissolved all trade unions and confiscated their assets, and imposed a curfew and a state of emergency. The 6 pm curfew would continue for a year and the state of emergency for four years.

The cinemas and theatre houses were shut down and the cinemas would never officially reopen their doors. The Institute of Theatre and Musical Studies, which was one of its kind, was also shut down for four years, forcing the students into exile or to shift their careers. The institute was also attacked by Jihadis during this period and all sculptures were attacked and broken. In fact, all the statues around Khartoum were demolished.

Dilapidated theater in Blue Nile State. Credit: Andariya.

There is a disagreement among intellectuals on whether the Islamist regime had a very clear vision when it came to Sudan’s cultural policy or not. Some believe that it had a very strict cultural policy inspired by its Civilizational Project, a manifesto that was never circulated, but was explained by the group’s godfather as an attempt to “reformulate the Sudanese society on the bases of Islam”. Some believe that for this reason, the regime gave the portfolios related to culture, legislative reform and social development and information to its most trusted inner circle. Others also believe that it came down to individuals and how they perceived culture, whereas cultural figures within the Islamist movement that wanted to support cultural activities would face attack by others who would send police forces to shut down the event. In an interview in 1992, Ahmed Al-Mardi, a Sudanese artist, said that the regime “have their own definition of artistic expression; they don't yet have a clear theory about it. But as long as the artist himself is regarded as a member or semi-member or just friendly with the movement, he might have the right to express himself, with the one exception that he can't use any sexual imagery.”

Consequences on the Artists and the Public

The Islamist regime and their Civilizational Project had a dire impact on the cultural scene. This complete impoverishment and even eradication of all artistic and cultural efforts was reinforced through a comprehensive legal framework. In fact, in their first decade in power, the Islamic front issued 93 new laws while 94 laws were developed in Sudan between 1903 to 1988.

The legal framework had several laws that facilitated the attack on artists and the public. For example, the public order law -which is also known as the morality code- has very loose articles that places penalties on dress-codes, mixing between the sexes and also loosely defines a brothel as “any place prepared for meetings of women or men, or men and women who have no marriage relationship nor related in circumstances where it is likely that sexual practices will take place”. A brothel became a private house and even a theatre, and as a result, it became the norm for private houses to be raided during private gatherings and parties.

In practice, the public order law had its own court system, police stations and thousands of public order officers who were notorious for targeting musical and cultural events. Al-Jamam Theatre group, a student and youth led theatre group that was established in 1993 at the height of the cultural crackdown, were used to being pursued by the public order police. In describing their everyday struggle, Mohamed Hanafi known as Capo, an actor and film-maker who was a member in Al-Jamam at the time, said:

“Sometimes they would storm the venue during the play and they would arrest us and the public. We were used to running from the police and I remember one time, we were performing at the University of Khartoum and the play was a historical play and when they came, we dispersed and started running, I remember thinking how strange we must’ve looked wearing our costumes and running down Nile Street. We would be arrested and every one of us would sign a document affirming that he or she will not take part in this activity again, but we do so the very next day. Our work in the theatre was our way of resistance.”

One of the most depressing memories for artists is how some of Sudan’s prized archival material was erased. Al-Bashir’s relative, Al-Tayeb Mustafa, who headed the broadcast entity in the early 1990s ordered the erasing of all materials that were against the Sharia laws. There have been efforts to persevere Sudan’s visual archive which goes back to the early 20th century, but much of the damage was already done.

In the brief period before the Institute of Theatre and Musical Studies was shut down for a period of four years, it was controlled and even forcibly moved to a new under-equipped campus, but the final whip was its closure as it represented one of the pillars of the cultural infrastructure that the artistic and cultural landscape depended on to survive, produce art and thrive in a country with scarce resources. The Sudanese Writers Union, cultural centers and the broadcast and print media were also part of this infrastructure and they were shut down and many artists and writers lost their livelihoods. This facilitated the brain drain process as many cultural figures who were not affected by political detention were affected by economic impoverishment and left the country en masse.

The Sudanese public that has for long consumed, appreciated and financially supported this scene was also under attack. Government policies saw over 600,000 arbitrarily sacked from their jobs to empower government loyalists. People were scrambling to survive day-by-day and on top of this, purchasing or enjoying any form of artistic production was prohibited or led to serious repercussions. When the public order police raid a concert, they do not only arrest the musical band; the audiences are often beaten and arrested. This made cultural activities a place for serious confrontation.

Moreover, acquiring musical tapes, films on videos, magazines and books led to persecution and entire units and a legal framework facilitated the imposed isolation of the Sudanese people from the outside world. In 1995, homes were raided for books, magazines and even art-work. Article 153 from the criminal law on “Materials and Expositions Contrary to Public Morals” was often used as a premise for the raid and subsequent confiscation and as a direct result, luggage was checked for items at the port and the airport. Various books were banned and incoming and outgoing mail was inspected by the security-operated Import and Export Bureau. In fact, even fax machines were confiscated.

Khartoum’s once promising art scene of the late 70s and 80s was now an impenetrable terrain for artists. The closure and destruction of much of the capital’s infrastructure ensured that arts production would be decreased tenfold or cease to a halt. Whatever had been spared by the NCP was immediately brought under their control and subjected to the newly instituted Islamist laws. Talal Afifi, creator of Sudan Film Factory, described best how the dogmatic changes in the way remaining institutions were run shaped the way artists who were entering their schooling engaged with art:

“There were things they didn’t shut down; there were [institutions] they ‘dried out’ instead. You have artists graduating from dried out curricula and institutions. That way you had artists with no applicable training- they’re only artists because they’re labeled that way- and [the government] can say you still have artists.”

The censorship brought forth by these laws also threw artists’ lives into disarray. Barred from freedom of speech, expression or a comprehensive education, artists looking to be employed within their field were forced to look for work within the surviving institutions that were now heavily monitored. With the job market ravaged by the NCP’s new measures against art, artists who were loud critics of the new regime and long-term commentators on the state of art and the sociopolitical landscape of Sudan were immediately displaced. The project budgets, job security, salaries and seniority of employees and artists that did not identify as part of the ruling party were either cut, decreased or revoked and funds were heavily diverted into using media channels as state-sponsored Islamic propaganda. However, the consequences of the coup on artists moved beyond displacement and into more extreme punishments. Afifi recounted what he knew of the history of violence that artists endured in first half-decade of the Islamist regime:

“The issues around remaining in Sudan weren’t simply about economic issues and the lack of opportunities; people were undergoing an extreme level of violence. There were people who went missing, people who were tortured, and many who died while incarcerated. This went on for almost a decade… Khojali Osman [who had escaped during the early days of the regime] was killed when he eventually returned… [the regime’s] tactics were like Hitler, they used torture and right wing ideologies; they were a war machine.”

Abandoned old sewing machines in Sennar. Credit: Andariya

Forced to escape due to threats, exile or livelihood, artists began to migrate. Around three million Sudanese artists and creatives relocated to Egypt during the 1990s. It became a microcosm of Sudan, with political chapters popping up, Sudanese newspapers, food and literary communities being established. Mohamed Wardi was not the only musician who went into exile, dozens of the most popular musicians such as Mustafa Sid-Ahmed, Yousif Al-Museli and dozens others left the country after threats, detention and intimidation. Wardi continued making music and provided opportunities for other artists to do so by flying out artists to 'Almarai', sans-serif !important for a few days to record their music. Sudanese music was recorded in Egypt for many years and the tapes would be smuggled into the country. Musicians suffered the most as concerts were banned and when they were organized, they were raided by the police. In the memorial service held for Mustafa Sid-Ahmed, an iconic musician who was forced into exile in the early 1990s and died in Qatar in 1996, the service was brutally attacked and members of Al-Jamam and Sawra, a musical band, were beaten.

The larger narrative of suppression and cultural loss that laid the foundation for the mass exodus of artists was framed by Dr. Mohamed Hassan, a linguist, critic and artist who, in order to explain the progress of the 1970s and 80s that artists had lost, described the beginnings of a rich artistic discourse when he was a student at the College of Fine Arts during the first half of the 1980s:

“[At the time] there wasn’t an academic leaning towards critique. New ideas started to appear concerning art theory and the role of art; a group of people who called themselves Madrasat al Khartoum, which was known for people like Ibrahim El-Salahi, Ahmed Ibrahim Abdel Aal, and younger artists who formed a youth subset… a group of artists who graduated in the seventies and began writing in the newspapers about how art that was being taught to Sudanese people was art that came from Europe with a European context and that we had our own problems. They started the discourse around identity; it was Madrasat al Khartoum that first proclaimed that we had a hybrid Afro-Arab identity, and it was tied to the different perspectives concerning Pan-Africanism that appeared in the sixties.”

The artists and thinkers who had just been beginning to grapple with Sudan’s colonial history and its effects on national identity— such as Khalil Farah, who Afifi commented was creating “from within the incubator of colonization, but still creating a narrative for the nation” —were suddenly barred from producing art or distributing it. The abruptness of Al-Bashir’s immediate implementation of new laws and Islamist standards proved to be a new beast. Artists who previously critiqued the inherent colonial mindset that influenced artistic schooling and the values of Sudan’s intelligentsia no longer had the outlet for their work due to the discontinued or censored newspapers. “What happened to art after Al-Bashir took over? These are the dark ages for researchers; I cannot find information about them,” I had commented to Dr. Hassan. “Unfortunately none of us has information,” he replied. “Obviously military governments rely on hiding information, and there were no newspapers, therefore there were no conversations between [us artists.]”

Some artists who were part of Madrasat al Khartoum or a part of its legacy, like Salah M. Hassan and Ibrahim El-Salahi, had already migrated due to pressure from the previous military government and found domiciles that provided them with resources, freedom and wide acclaim. This international acclaim did not come without its fair share of xenophobia and inaccessibility of course; El-Salahi once commented, “[African artists] are kept in the dark. We are kept outside in the cold.” Neither Hassan nor El-Salahi ever moved back to Sudan. In Every Slight Movement of the People… Is Everything: Sondra Hale and Sudanese Art by Susan Slyomovics, an email correspondence between Hale and the aforementioned author gives us a glimpse into where some of the artists who left or were exiled during Sudan’s turbulent post-independence years were living:

“I interviewed three Sudanese artists in 'Almarai', sans-serif !important (Hussein Shariffe, Hasaan Ahmed, and Seif ol-Islam) in the early 2000’s—two trips; and interviewed [Mohamed Omer] Bushara in Asmara twice in 1994 and 1996 (he came from Saudi Arabia to spend three months with me each time), as well as other Sudanese artists. Tahir Bushra Murad lived with us in the early 2000’s for nine months and I dialogued with him daily. I also studied his work (but did not interview him) in Asmara and Addis (he was in exile). Khalid Kodi I interviewed during two trips to the east coast (Boston) and Midwest for the Sudan Studies Association meetings and/or [the Middle East Studies Association]. Bushara and Ibrahim el-Salahi, I interviewed in Oxford in the late 1990s and early 2000s.”

Of the artists who stayed behind, whether due to personal choice, financial reasons or inability to leave, some resolved to resist the violence. “For the first seven years after 1989, people wanted to make political statements and stances; some artists joined guerrilla armies to fight against the regime’s violence,” Afifi said. The political sanctions that resulted from Al-Bashir’s regime put Sudan on an international blacklist that made— and still makes— it difficult for artists to apply to scholarships and fellowships, or simply import materials that they need for their work. As a gallerist named Mustafa described, “When I was starting [my gallery] there were no framing shops in Sudan. We tried to rely on local materials. U.S sanctions and inflation make it difficult to import painting tools, raw materials like wood that [gallery owners] or artists need.” Of the artists who remained in Sudan, many turned to taking day jobs to provide them with a stream of income. Artistry— especially in the fine arts— was no longer a talent that could be easily nurtured or lead to a feasible profession.

Bridging the Gap: The Past and the Present

The restrictions on art production, expression and values did not just encompass the immediate upheaval of the art world and the strict retaliation towards anybody who did not actively, publicly and socially embody Islamic laws or went further than submission and dared to resist; they sought to forcibly and permanently instill Islamist values into the population. The NCP had essentially begun a long-term ideological war on art that began in 1989 and spanned the three decades during which they were in power. The effects of this ideological war changed the Sudanese community’s personal views, social values, attitudes towards creativity, relationship with censorship and stances on diversity and freedom. This transformation undoubtedly happened through the decisions made towards suppressing artists and free-thinkers as well as the affected culture of art in Sudan. Art in Sudan was thus transformed. Dr. Hassan’s reflections on the inherited colonial mindset that plagued the arts community in the 1970s are mirrored in Afifi’s comments about the NCP creating people who were only artists by name. While the tangible effects of British colonialism on artistic values consequently made it difficult in the 1970s to create true artists who could explore the abstract world rather than skilled technicians who could only reproduce reality, now we have the ‘dried curricula” that don’t offer support to art students who want to critically explore society through their work. The emaciated education of arts institutes were cemented by Islamist ideologies that were inserted into the artists. Speaking of the endurance of these ideologies and how they curb artists’ critical thought to this day, Dr. Hassan recounted:

“There were so many things that Al-Bashir did… they created an antagonism towards art, the College of Fine Arts was subjected to antagonism and attacks. I mean, [the government] destroyed statues. A number of sculpted works were destroyed and several graduating classes’ exhibitions were destroyed. They thought sculpting was haram. There was a statue at the University of Khartoum.. they removed it and destroyed it… there was a martyr's monument near the railroad tracks that was destroyed. They said that every piece of visual art that had symbolic meaning or was attached to a memory was a sanam. And for Muslims sanams are haram. These beliefs still exist in the newer generations. I currently struggle a lot with my art students; a lot of them have negative attitudes towards things relating to sculpting.”

Alongside the destruction of monuments, archives, libraries, and exhibition halls, student dormitories were closed which reversed the rural population influx into the city that had shaped postcolonial Khartoum and made it a more authentic microcosm of Sudan. Despite initial disgruntled views towards that migration of rural Sudanese into the capital after independence, it was this movement that changed not only the culture of the city but its urban landscape. The British colonial architecture of Gordon College and government buildings was no longer the central theme in Khartoum with the new local shops, houses, storefronts, and markets that appeared with the diversity in the increase of Khartoum’s population. This was all stopped with the closure of and decrease in accommodation that allowed people from outside Khartoum to come to the city for their higher education. Where the 1970s and 80s saw the beginnings of an uptick in diverse artistic views and expressions, the 90s created uniform, centralized populations by “putting people into the factory” and focusing on creating a militant and political mentality with their events.

The erasure of music that expressed romance or any hedonistic and carnal pleasure from radios, violence against women whose fashion did not express modesty or align with local tradition, home raids that allowed the government to remove banned art and literature from people’s private residences slowly started removing art from public consciousness over the years. Schoolchildren were required to wear new uniforms that were designed in a military fashion. Around 180 artists were dead within the first eight years and their art was lost forever. Unlike El-Salahi or Kamala Ishaq, some artists who left, such as actresses who were just beginning to gain fame in Sudan and Egypt, migrated to find little success or opportunity abroad. If the effect of this oppression did not injure artists physically, it was felt psychologically. People lost their lives in every sense of the word; careers that were once flourishing or promising were ended, life works destroyed, opposition suppressed. The physical and psychological brutality was immeasurable, with much of it lost to us today due to the government’s intentional lack of documentation. It is inconceivable to today’s generation that grew up believing Sudan was always a conservative country that it once had a flourishing nightlife, a rich visual culture, and famous local artists. “Khartoum in the eighties / my mother with ribbons in her hair/dress fanning about her nutmeg calves… the borrowed record player / the generation that would leave / to make nostalgia of these nights,” the poet Safia Elhillo wrote; the only remnants of that past are the parents who survived long enough to tell their children about the parties, bars, and cinemas where they congregated when they were younger.

With the population’s memory being altered over time to incorporate Islamic bias via destruction and removal of art, the vibrant art culture of Khartoum went underground after being suppressed. On the surface, it seemed as though the lack of infrastructure for arts production, the dispersal and death of many artists, and the absence of cinemas and galleries permanently stilled Sudan’s culture of engagement with visual art. “The destruction that happened to Sudanese cinema… afterwards nobody had any knowledge of the visual. From the perspective of seeing something in front of you, on a street level, on a screen level, there were no images,” Dr. Hassan recalled. The 2010s saw a slow rebuilding of the visible art world in Khartoum, with Talal Afifi’s Sudan Film Factory and Mustafa Ali’s Mojo gallery, amongst many others who began organizations and businesses because they “loved art and didn’t have access to an art fix.”

In 2017 Al Jazeera released a short witness documentary titled ‘Sudan’s Forgotten Films” that followed two men, Benjamin and Awad, who ran the film archive which, although containing thousands of rare single-copy film reels, had fallen into disrepair due to under-funding and extreme neglect. The emotional response of the people who watched it was strong and angry; many were upset at all that was lost and all that is sure to be lost because of the Inqaz government’s war on art. Although Al-Bashir had done a lot to ensure that Sudan’s relationship with meaningful, impactful art would be severed and crippled over time, artistic expression was hanging on by a thread that was strengthened over time as people slowly built an immunity towards the violence and the underground— and diaspora—art world began to grow.

Conclusion

The explosion of revolutionary art in 2019 was a result of three decades of local, underground resistance. Social media facilitated the flame of resistance by providing an outlet for visual art and messaging to spread by reaching millions of Sudanese, both in the country and the diaspora. Unlike 1964’s middle-class led revolution, the 2019 uprising arose from the populations of Sudan that had been oppressed and dismissed for decades: the descendants of indentured and enslaved Sudanese, communities on the outskirts of Khartoum and in cities across Sudan, and the general working class population that got angrier as public transportation became more inaccessible, bread became more expensive, and inflation made their money worthless. The astonishment of the middle class, upper class, and diaspora Sudanese falsely constructed the narrative that the explosive mobilization of art as a tool for resistance was a surprise. This narrative not only suppresses the truth of the revolution’s beginnings but sets the stage for the co-opting of the real organizing communities’ mobilizing efforts, such as Al-Damazin, where the protests first sparked. As Afifi put it:

“We think it is new because we’re middle class; we thought it was new but we just couldn’t hear it. It’s always been there. [The 2019 uprising’s] resistance was gritty and angry; it wasn’t the resistance of the middle class that was concerned with being respectable or polished. They weren’t concerned with filiality or propriety. The art came from a suffocated community that didn’t see the wall as a canvas upon which they should paint. The murals were akin to the angry writing on the bathroom wall that a person would write about their bully, the scribble on the stall that says ‘**** so and so.’”

While several negative outcomes such as the commercialization of revolutionary art and the historical misconstruction of the revolution’s beginnings may be prophesied, the fact remains that the uprising facilitated a large-scale public re-engagement with art that had been missing from Sudan for the past three decades. While Sudan’s civic and legal relationship with artists never allowed them to move past the promising beginnings of the ‘honeymoon’ phase and into the labyrinthian, complex, and often divisive nature of social discourse, it now has its first real chance in over thirty years to embark on that road.

Notes and References

1. Elmileik, Aya. “What Prompted the Protests in Sudan?” News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera, December 26, 2018. <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/12/prompted-protests-sudan-181224114651302.html.>

2. Dahir, Abdi Latif. “Sudan’s street protests have inspired another revolution—in art” The Art of Protests | Quartz Africa, July 12, 2019. <https://qz.com/africa/1664733/sudans-protests-inspire-art-graffiti-revolution/>

3. Popular songs such as Sudan Bedoun Kizan which translates into Sudan without the Keizan (the Islamist government), Min Tehet Al-Ramad which translates into from under the ashes and others became widely popular.

4. AbdelRazik, Asmi. “The Popular Randook, the language of the periphery revolting against the state.” Ultra Sudan | Ultra Sawt, July 19, 2019. <https://bit.ly/2Pwx97d>

5. Zari Sudan. “ Kolen Kolen turned to Let it fall, that is all at a wedding in harmony with Mohamed Al-Rayan against Omer Al-Bashir. YouTube Video. 00:14. January 21, 2019. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kafe_el_SkU>

6. Bektas, Umit. “Sudan protesters' sit-in inspires cultural outpouring”. World News | Reuters, May 7, 2019. <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-sudan-politics-art/sudan-protesters-sit-in-inspires-cultural-outpouring-idUSKCN1SD0WJ>

7. Warburg, G.R, “The Shari´a in Sudan: Implementation and repercussions, 1983-1989,” Middle East Journal 44 (1990): pp. 624-637.

8. Pace, Eric (1971, July 27). A Top Red Hanged by the Sudanese. New York Times. P.1. Retrieved from <https://nyti.ms/3chYXWJ>

9. Blue Stars were called “Nimeri’s band” at the time. They continue to perform at Papa Costa and other places in Khartoum.

10. Interview by author with Mohamed Hanafi “Capo”, filmmaker and actor, Khartoum, 26 February 2020, Khartoum.

11. Shareef, Salah A. “Umat Al-Amjad, Mayo Revolution Song.” YouTube Video. 10:38. July 14, 2013.

12. Youtube video of the anthem of the nation of glory (the songs of the May revolution). Salah Awad Shareef’s Channel. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-1BLNeZXF64

13. Abdelrhman, W.S. (2017). DANCING TO THE MELODIES OF WHIPS: The Implications of Sudan’s Sharia Laws on Art and Media. [ Dissertation]. School of Law, University of Essex.

14. Salih, Kamal Osman, “The Sudan, 1985-9: The Fading Democracy” The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Jun., 1990): pp. 199-224.

15. Kaballo, Sidgi A. “Sudan Coup in Khartoum: Will It Abort the Peace Process?”. Review of African Political Economy. No. 44, Ethiopia: 15 Years on (1989), pp. 75-78.

16. Human Rights Watch. Behind the Red Line: Political Repression in Sudan, 1996, ISBN 1-56432-164-9.

17. Ayin. “AlIslamion wa Alada’a Altarikhi Lil Thagafa” Ayin, November 23, 2015 https://3ayin.com/ Islamists and the historical hostility to culture.

18. Interview by author with Mohamed Ismail, Head of Culture Affairs unit at Al-Khartoum Newspaper, Khartoum, 26 February 2020.

19. Interview by author with Talal Afifi filmmaker and founder of Sudan Film Factory, Khartoum, 5 February 2020, Khartoum.

20. Kirker, Constance L. “‘This Is Not Your Time Here’: Islamic Fundamentalism and Art in Sudan: An African Artist Interviewed,” Issue: A Journal of Opinion (African Studies Association), 20:2 (1992), 5–11.

21. The Penal Code 1991. European Country of Origin Information Network. chrome-www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1219135/1329_1202725629_sb106-sud-criminalact1991.pdf

22. Gasemalbari, Suhaib. “Sudan’s Forgotten Films” -Al-Jazeera | Witness, Oct 22, 2017 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NUPlYMjC4FY>

23. Younis, Ahmed. “Half a Million Arbitarily Sacked Civil Servants to Sue Sudan’s Bashir. Asharq AlAwsat. November 18, 2019. <https://bit.ly/2TrBdXw>

24. Many intellectuals had their libraries confiscated. When Mohamed Hanafi Capo was arrested as a high-school student in the early 1990s, two boxes full of books were confiscated from his house.

25. Ali, Haidar Ibrahim. Sogot Almashru’ Alhadari (the Fall of the Civilization Project), Sudanese Studies Centre Print, 2004.

26. Figure provided by interviewee; could not be confirmed as of date. Interview with Talal Afifi. 5 February 2020.

27. One of Sawra’s members saw his bass-guitar broken as they smashed it to his head.

28. Interview by author with Dr. Mohammed Hassan, Professor in the Fine Arts Department at Neilein University, Khartoum, 24 February 2020.

29. The Culture Show - Who Are You Calling an African Artist? Youtube Upload. Art Documentaries, Jul 24, 2013. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=srWIeMyQcgk>

30. Slyomovics, Susan. “Every Slight Movement of the People… is Everything”: Sondra Hale and Sudanese Art. Source: Journal of Middle East Women's Studies , Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 15-40. Duke University Press.

31. Interview by author with Mustafa Ali, owner of Mojo Gallery, Khartoum, 23 February 2020.

32. A statue of a deity or important figure that worshipers typically pray to or in front of; this is a practice greatly forbidden in Islam.

33. Alkam, Abdallah. “Algorashi Yatouh Fi Shawari’ AlKhartoum”, Sudanile, 2010 <http://sudanile.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=15136:$-2bAA_&catid=142&Itemid=55>

34. Bahreldin, Ibrahim & Osman, Omer & Osman, Amira. (2014). Architecture in Sudan 1900-2014; An Endeavor Against the Odds. 10.13140/RG.2.1.1856.7848.

35. Kodah, Luc. “Change School Uniform - First Step towards Peace Building.” Sudan Tribune, May 16, 2006.< www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article15785>

36. “The Lovers.” The January Children, by Safia Elhillo, University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

37. Geal Gadid, Ana Tala Afifi wa Sudan Film Factory, 23 January 2015, Issue Number 21-Cinema https://gealgaded2014.wordpress.com

**

This research was carried out with the support of a grant received through the “Research on the Arts Program” Second Cycle (2020-2021), from the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture and the Arab Council for the Social Sciences funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The views expressed in this production are those of its makers and interviewees and do not necessarily represent those of the ACSS.