The Ujamaa policy headed by Mwalimu J.k. Nyerere was the first post colonial project that aimed at primary industrial investment. (Photo source: AKEM)

Primary industrialization in Tanzania began during the colonial era. The main focus of manufacturing in Tanzania was on primary, low value, labor-intensive agricultural goods. Before the First World War (WWI) German colonizers established a company called the German East Africa Company in mainland Tanzania. The economic performance of the colony was awash with potential and prior to the beginning of WWI the company’s exports were twice as high as those of British East Africa, which operated in the neighboring British colony of Kenya.

Due to the constraints posed by the financing of the war and the associated production and trade interruption, the German East African company performance suffered, as the colony could not produce for outside markets. Consequently, there were no imports, and industries which produced goods for military purposes experienced higher growth levels. This led to the general decline of the industrial sector in Tanzania.

Post-independence Primary Industrialization

Right after the Tanganyika independence in 1961, new projects to reclaim the industrial markets began. The goal was not only to reclaim the sector, but to also introduce it as the main project for national post colonial development in the country. This started by introducing the three-year development plan (TYP) for 1961–1964 and the First Five-year Plan (FFYP) for 1964–1969. The TYP aimed at promoting growth mainly through increasing investment in those activities that were expected to bring quick and high returns.

The TYP was successful in promoting basic consumer goods processing industries through the incentives outlined, as well as providing a public injection of funds from the government through the Tanganyika Development Corporation. Under the TYP manufacturing units started to increase in numbers as did the level of output. In 1965, there were 569 manufacturing establishments employing ten persons or more of which over one-third came into existence after independence. These industries included aluminum sheets, screws, nails, wire, enamelware, and razor blades.

However, despite commensurate gains in manufacturing, the level of industrial output remained comparatively low. In 1966, the industrial output share in total production was only 6.6 per cent, below the expected level of 10 per cent.

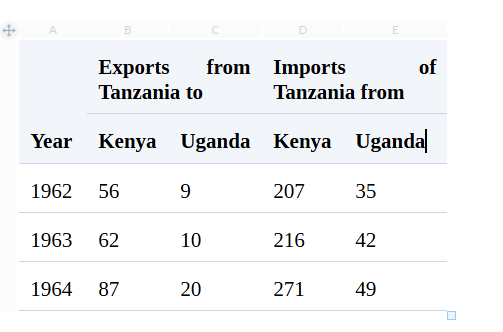

The table shows the uneven gap between the imports and the exports of goods in Tanzania. ( source: Jamal Msami)

The Arusha declaration started to advocate the utilization of local resources as primary endowments in production, and in effect signaled the end of low level direct regulatory control and the reliance on foreign private investors. Nationalization of large foreign owned enterprises ensued as did the expansion of the public sector. Increased state control in manufacturing saw the introduction of an industrial licensing procedure under the National Industries Licensing and Registration Act of 1967.

Between 1967 and 1973, Tanzania recorded the most rapid growth of manufacturing value added (for enterprises employing ten or more personnel) in its history. It should be noted that the increase in manufacturing also coincided with an increase in both absolute and relative labor productivity.

It is also important to note that one of the major ways Tanzanian government promoted self reliance in means of production was by enforcing trade restrictions. This was aimed at producers of export cash crops, mainly coffee, cashew nuts, sisal, tea, and tobacco. Traditionally Tanzania's main source of export earnings had to sell their products to marketing parastatals (quasi-governmental organizations) which offered prices well below global prices. Similarly, all imports were regulated through administrative allocations of foreign exchange and an import-licensing system, both of which became increasingly restrictive toward the end of the 1970s as foreign exchange earnings declined.

Of course this did not come without consequences. The overall result was that per capita output of export crops fell by about 50 percent during 1970-82 as the share of food production in agricultural output increased. Other (nontraditional) exports also contracted sharply during this period, owing to the pervasive administrative restrictions imposed on them. Falling export earnings also led to foreign exchange shortages.

The consequent drop in imports of intermediate goods and raw materials led to sharp cutbacks in production, especially in the highly import-dependent industrial sector, and to deterioration of the country's infrastructure and the general economy which was further affected by the country’s financial imbalances in the 80s.

Primary Industrialization in the Present

Tanzania's experience with restricted trade system through primary industrialization is a huge indicator of the adverse consequences of a restrictive trade regime and the associated cost-price on longer-term macroeconomic performance. In the 1970s and early 1980s, trade distortions reduced the profitability of export crops, leading to a sharp contraction in export earnings and foreign exchange shortages.

Despite the imposition of tight import controls, these shortages led to reductions in critical imports of intermediate goods and raw materials, cutbacks in industrial production, and deterioration of the country's infrastructure. The phasing out of trade restrictions since the mid-1980s played a key role in the revival of the export and import sector which also brought the recovery and rationalization of primary and export focused industries, and re-established the foundations for sustainable growth and development in the country.

Tanzania’s industrial sector production reached USD 13.5 billion (33% of GDP) in 2018, compared to USD 9.1 billion in 2014, marking an increase of 48%. The government aims to make Tanzania a semi-industrialized nation by 2030, with a significant contribution from the industrial sector to the GDP. The industrial sector of Tanzania currently comprises of several key subsectors that significantly contribute to its GDP, namely construction, manufacturing, mining, electricity supply, water supply, sewerage, and waste management.

One of the most promising manufacturing primary industries in Tanzania is the textile industry. This industry has evolved tremendously since independence to date from a time when the industries were owned by the government to private ownership. Textiles and garments remain a compelling opportunity with output and exports rising to the demands of US, EU and Asian markets.

The textile industry in the country does face challenges, one being competition from international markets through the trade liberalization policy; which has allowed influx of clothes from other countries that produce superior quality and at an affordable price. This can be solved through effective use of media, marketing and effective trade policy.

Another serious challenge is the use of old machines and equipment. Outdated machines and equipment and the inability to access timely new technology are revealed by many textile firms as a serious hindrance. Investment in science and technology would be a remedy to revive the sector. Allocation of more funds to specialized manufacturing programs in colleges such as textile and research should also be a priority.

METL is one of the biggest textile industries in Tanzania that shows a promising future with significant contribution to the economy through local market as well as serving several foreign markets in ASIA, USA and Southern Africa. (Photo source: METL Group)

conclusion

Economic independence is an ongoing journey, not a destination. Tanzania has gone through different phases since its independence and it is still on its way. Primary industrialization needs to work hand in hand with other tools of the economy such as other industrial sectors, importation, exportation, and agriculture to reach economic independence. It’s a unison of keys that need to be played together to form a rhythmic pattern. One cannot simply exist without the others.