Inscribed above the entrance to the temple of Apollo at Delphi about 2,500 years ago are the words “Know Thyself.” In ancient Greece, people would visit the oracle hoping to find out what destiny had in store for them or what course of action to take in a particular situation. What does it exactly mean to have self-knowledge? How does one go about getting it? And why should one want to have it?

The Temple at Delphi. Source: Bernard Gagnon

From a very young age, I so much wanted to know about almost everything; “why is the sky blue?”, “what causes rain?”, “Why did the sun follow me on every turn that I took?” Lucky for me, I have a brother who would always try to answer most of these questions. Growing up with him, I would always have these discussions about the world, where I would ask all sorts of questions and then listen so that I would be able to absorb the answers. My brother was into science and technology and everything he did, revolved around it.

Involuntarily, my mind was tuned towards science, and my questions were within the realm of science. Questions about space, the world, and how it works. It later occurred to me that all these questions were only important in answering everything outside of myself. As an immensely curious person, I also wanted to know about myself, I wanted to know why I live my life the way I lived it, and why I do the things that I do.

I was not in the middle of an existential crisis as some would say but rather, I was starting my journey towards self-discovery. “Was there a question I would ask somebody else about myself and they would have the right answer for me?” I thought to myself. Truth is, my brother would easily have told me about myself, but what he would share with me would be a subjective opinion about me. I wanted to know this “me" for myself and the only way I would start getting these answers was by looking into myself—I should be the one trying to answer the questions that I was asking. I needed spiritual awakening to find myself and answer all these personal questions.

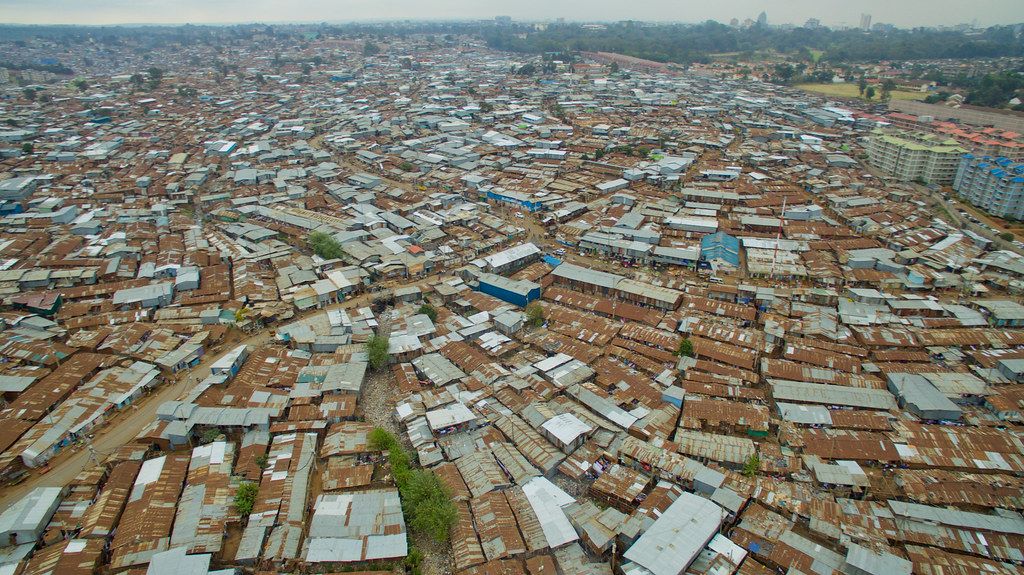

I grew up in Kibera, a suburb of Kenya’s capital Nairobi and like most people, I was born into a religious family. My dad and mum were devoted Christians who didn’t miss a Sunday service and with each visit to the church, they brought my siblings and me along with them.

Kibera - one of Africa’s largest slums located on the outskirts of Nairobi. Source: Grid Arendal

I can proudly say that I owe them largely for starting a spark that rekindled a flame that became my spiritual life. My mother taught me how a Christian should appreciate the life that God has given them by offering praise and worship to Him. My father on the other hand taught me how a Christian should treat his fellow man, with his favorite quote being one from the scriptures, “Love your neighbors as you love yourself.”

With every teaching I received from my parents, I grew stronger in faith but I felt I didn’t fully settle for just a religion. I wanted to start loving my neighbors as I loved myself, but do I truly love myself? Even if I did, what kind of love would it be? Is it a genuine love or one that was conditional? It seemed to me that as I stayed entangled in my religious beliefs, there was always a need to answer personal questions about myself.

The scriptures have a lot of valuable lessons that can be applied to an individual's life for a positive change, but was it enough? For me, it seems to lack the flexibility that should come with understanding the ever-changing perplexity of the human condition.

My life, just like any other person’s life has not been smooth, with a mix of good and bad times. It has been a jumble of heartbreaks, poverty, lies from people, and even lies that I told myself. My distressing reality has made me draw the line between being religious and being spiritual. In my opinion, you can be religious and not spiritual, and vice-versa.

What is Spirituality?

Before going any further, I should address the animosity that many readers feel towards the term spiritual. Whenever this word is used anywhere, it carries with it ambiguity. The term “spiritual” has become entangled with beliefs about immaterial souls, supernatural beings, ghosts, and so forth.

It acquired other meanings as well. We speak of the spirit as an essential principle or volatile substance such as liquors. Nevertheless, many nonbelievers now consider all things “spiritual” to be contaminated by some sort of superstition.

However, I do not share their semantic concerns. I share the concern, expressed by many atheists that the terms spiritual and mystical are often used to make claims not merely about the quality of certain experiences, but about reality at large. Far too often, I think that these words are invoked in support of religious beliefs that are morally and intellectually perverted.

Deeper scrutiny and openness about myself have helped me understand that there must be an essential way one can direct his life through this spiritual light; and that is, by understanding one’s self. I believe my life is not much different from other people’s but perhaps, I should speak only for myself.

It seems that I spend much of my waking life in a state of mind in which my conscientiousness feels fragile, and most voluntary actions I take are either poor or missing. It is as if I lack some essential element that can give my life a synchronizing harmony. I am yet to have a sophisticated spiritual understanding of myself.

I spent one afternoon at Kidepo Valley National Park in Uganda, on top of a mountain looking down the valley where this beautiful game reserve spread across. On this infernally hot day, I could see the ground sort of radiating from afar and the hot air was forming a uniform mirage across the entire valley. “These hot conditions must be really devastating for wildlife” I exclaimed a remark to a game guardian I toured with. She responded that that was not true as the region was experiencing an imminent annual dry season, adding that animals in the park had fully adapted to such conditions and could thrive competently.

A beautiful view of the landscape in Kidepo valley national park. Source: Morris J. Mel

To be honest, I never saw a lot of wildlife, because from where I was standing, you would need binoculars to magnify and scrutinize the beautiful landscape. As I was gazing at the surrounding mountains, a feeling of peace suddenly came over me. It soon grew to a blissful stillness that silenced my thoughts.

In an instant, the sense of being a separate self an “I" or a “me" vanished. Everything was as it had been—the cloudless sky, the brown mountains sloping towards the valley, the hot sun blazing—but I no longer felt separate from the scene while peering out at the world from behind my eyes. Only the world remained. It was a really special moment for me.

The experience lasted just a few seconds, but it returned many times as I looked out over the land and mountains. I might believe that I had glimpsed the oneness of God or been touched by the Holy Spirit. If I were a Hindu, I might think in terms of Brahman, the eternal self, of which the world and all individual minds are thought to be a mere refitting. If I were a Buddhist, I might talk about the “dharmakaya of emptiness,” in which all apparent things manifest as if in a dream.

However, I am simply someone who is making his best effort to be a rational human being. Consequently, I am a very slow person when it comes to drawing metaphysical conclusions from experiences of this sort, yet I glimpse this consciousness every day. Whether at a game reserve, or in my bedroom, while brushing my teeth, or when simply taking a walk outside, I have discovered that it is possible to be at ease in the world for no reason, if only for a few moments at a time, and that such ease is synonymous with transcending the apparent boundaries of the self.

I actually remember waking up one afternoon and watching all these tiny particles of dust floating listlessly in the sunlight that was pouring in through the window. It was really quiet like everything sought to be observed for the first time, so clear in my eyes. This particular moment gave me a certain realization of all the serenity of life that went through my eyes. Truth is, I instantly grew attached to wanting to have more of these intoxicating states of consciousness as a perpetual pattern in my everyday life.

I was now seeking something spiritual in every sense of the word, to enhance my understanding of self. It was not until I ended up discovering a practical gem that has forever changed my life, and that was the practice of meditation.

Introduction to Dzogchen

Throughout my life, I came across the word "meditation" a tremendous number of times— when listening to a podcast, when reading a book, even when watching television. My prejudice towards it simply thought of it as one of the other many conventional religious practices that had their principles affiliated with superstition.

That wasn't the case anymore when I discovered the Dzogchen, a formal initiation in which a teacher seeks to impart the experience of self-transcendence directly to a student. I received this teaching from several Dzogchen books.

The practice of Dzogchen requires that one be able to experience the intrinsic selflessness of awareness in every moment (that is, when one is not otherwise distracted by thought) which is to say that for a Dzogchen mediator, mindfulness must be equivalent to dispelling the illusion of the self.

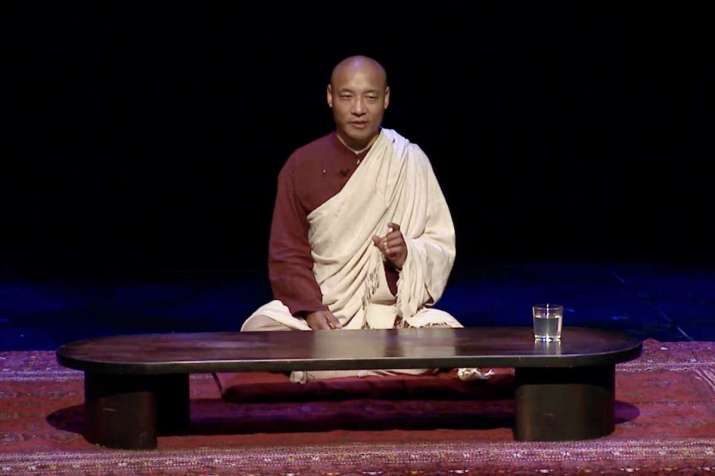

Anam Thubten Rinpoche the founder and spiritual advisor of Dharmata Foundation practices Dzogchen. Source: Global Buddhist Door

Rather than teach a technique of meditation such as paying close attention to one’s breathing, a Dzogchen master must precipitate an insight on the basis of which a student can thereafter practice a form of awareness that is free from subject/object dualism. Thus, it is often said that, in Dzogchen, one “takes the goal as the path” because the freedom from self that one might otherwise seek is the very thing that one practices.

The goal of Dzogchen, if one can call it such, is to grow increasingly familiar with this way of being in the world. In my experience, while I was learning this practice, most masters simply described the view of consciousness without giving clear instructions on how to glimpse it.

The genius of my most celebrated master, Tulku Urgyen was that he could point out the nature of the mind with the precision and matter-of-factness of teaching a person how to thread a needle, and could get an ordinary person like me to recognize that consciousness is intrinsically free of self.

There might be some initial struggle and uncertainty, depending on the student, but once the truth of non-duality had been glimpsed, it became obvious to me that it was always available—and there was never any doubt about how to see it again. I started reading Tulku Urgyen yearning for the experience of self-transcendence, and in a few minutes, he showed me that I had no self to transcend.

This instruction was, without question, the most important thing I have ever been explicitly taught by another human being. It has given me a way to escape the usual tides of psychological suffering—fear, anger, shame—in an instant.

I had ceased to be concerned about myself. I was no longer anxious, self-critical, guarded by irony, in competition, avoiding embarrassment, ruminating about the past and future, or making any other gesture of thought or attention that separated me from the world. I was no longer watching myself through another person’s eyes.

Honestly speaking, at my level of practice, this freedom lasts only a few moments but these moments can be repeated, and they can grow in duration. Punctuating ordinary experience in this way makes all the difference.

In fact, when I pay attention, it is impossible for me to feel like a self at all: the implied center of cognition and emotion simply falls away, and it is obvious that consciousness is never truly confined by what it knows. That which is aware of sadness is not sad. That which is aware of fear is not fearful. The moment I am lost in thought, however, I am as confused as anyone else.

Mindfulness

There is nothing passive about mindfulness. One might even say that it expresses a specific kind of passion, a passion for discerning what is subjectively real in every moment. It is a mode of cognition that is, above all, undistracted, accepting and (ultimately) non-conceptual.

Being mindful is not a matter of thinking more clearly about the experience. It is the act of experiencing more clearly, including the arising of thoughts themselves. Mindfulness is a vivid awareness of whatever is appearing in one’s mind or body: thoughts, sensations, and moods, without grasping at the pleasant or recoiling from the unpleasant.

One of the great strengths of this technique of meditation, from a secular point of view, is that it does not require us to adopt any cultural affectations or unjustified beliefs. It simply demands that we pay close attention to the flow of experience in each moment.

The enemy of mindfulness or of any meditative practice is our deeply conditioned habit of being distracted by thoughts. The problem is not thoughts themselves but the state of thinking without knowing that we are thinking. In fact, thoughts of all kinds can be perfectly good objects of mindfulness.

In the early stages of one’s practice, however, the arising of thought will be more or less synonymous with a distraction that causes a failure to meditate. Most people who believe they are meditating are merely thinking with their eyes closed.

A photo of a woman practicing mindful meditation. Source: www.onlymyhealth.com

By practicing mindfulness, however, one can awaken from the dream of discursive thought and begin to see each arising image, idea, or a bit of language vanish without a trace. What remains is consciousness itself, with its attendant sights, sounds, sensations, and thoughts appearing and changing in every moment.

At the beginning of one’s meditation practice, the difference between ordinary experience and what one comes to consider “mindfulness” is not very clear, and it takes some training to distinguish between being lost in thought and seeing thoughts for what they are. In this sense, learning to meditate is just like acquiring any other skill. It takes thousands of repetitions to throw a good jab or to coax music from the strings of a guitar.

With practice, mindfulness becomes a well-formed habit of attention, and the difference between it and ordinary thinking will become increasingly clear. Eventually, it begins to seem as if you are repeatedly awakening from a dream to find yourself safely in bed. No matter how terrible the dream is, the relief is instantaneous. And yet it is difficult to stay awake for more than a few seconds at a time.

My friend once likened this shift in awareness to the experience of being fully immersed in a film and then suddenly realizing that you are sitting in a theater watching a mere play of light on a wall. Your every waking moment is lost in the movie of our lives. Until we see that an alternative to this enchantment exists, we are entirely at the mercy of appearances.

Again, the difference I am describing is not a matter of achieving a new conceptual understanding or of adopting new beliefs about the nature of reality. The change comes when we experience the present moment prior to the arising of thought.

Suffering may not be inherent in life, but dissatisfaction is. We crave lasting happiness in the midst of change: our bodies age, cherished objects break, pleasures fade, relationships fail. Our attachment to the good things in life and our aversion to the bad amount to a denial of these realities, and this inevitably leads to feelings of dissatisfaction.

Mindfulness is a technique for achieving equanimity amid the flux, allowing us to simply be aware of the quality of experience in each moment, whether pleasant or unpleasant. This may seem like a recipe for apathy, but it needn’t be. It is actually possible to be mindful—and, therefore, to be at peace with the present moment—even while working to change the world for the better.

Understanding Traditional Spirituality

Given this change in my perception of the world, I now have a better understanding of the attractions of traditional spirituality. I also recognize the needless confusion and harm that inevitably arise from the doctrines of faith-based religion.

I did not have to believe anything irrational about the universe, or about my place within it, to learn the practice of Dzogchen. I didn’t have to accept Tibetan Buddhist beliefs about karma and rebirth or imagine that Tulku Urgyen or the other meditation masters I read about possessed magic powers.

Whatever the traditional liabilities of the guru-devotee relationship, I know from direct experience that it is possible to meet a teacher who can deliver the goods. Nevertheless, it is a fact that a condition of selfless well-being is there to be glimpsed in each moment. Of course, I am not claiming to have experienced all such states, but I meet many people who appear to have experienced none of them and these people often profess to have no interest in spiritual life.

After I was introduced to the practice of Dzogchen, I realized that much of my time spent meditating had been a way of actively overlooking the very insight I was seeking. It would seem that very few good things in life come from our accepting the present moment as it is. To become educated, we must be motivated to learn. To master a sport requires that we continually improve our performance and overcome our resistance to physical exertion. To be a better spouse or parent, we often must make a deliberate effort to change ourselves.

Merely accepting that we are lazy, distracted, petty, easily provoked to be angry, and inclined to waste our time in ways that we will later regret is not a path to happiness. Yet it is true that meditation requires total acceptance of what is given in the present moment. If you are injured and in pain, the path to mental peace can be traversed in a single step: simply accept the pain as it arises, while doing whatever you need to do to help your body heal. If you are anxious before giving a speech, become willing to feel the anxiety fully, so that it becomes a meaningless pattern of energy in your mind and body.

Embracing the contents of consciousness in any moment is a very powerful way of training yourself to respond differently to adversity. However, it is important to distinguish between accepting unpleasant sensations and emotions as a strategy while covertly hoping that they will go away, and truly accepting them as ephemeral appearances in consciousness.

Only the latter gesture opens the door to wisdom and lasting change. The paradox is that we can become wiser and more compassionate and live more fulfilling lives by refusing to be who we have tended to be in the past. We must also relax, accepting things as they are in the present, as we strive to change ourselves.

In my view, the realistic goal to be attained through spiritual practice is not some permanent state of enlightenment that admits no further efforts, but a capacity to be free in this moment, in the midst of whatever is happening. If you can do that, you have already solved most of the problems you will encounter in life.