Technology is spreading quickly across Africa, but the CIPESA State of Internet Freedom 2024 report shows a worrying trend. At least ten countries, including Kenya, Ethiopia, and Mozambique, have cut internet service in order to suppress protests and silence dissenting voices during election periods. Surveillance in Africa has also shifted from broad data collection to more targeted methods. Governments in Rwanda, Egypt, and Togo have reportedly used advanced spyware to monitor activists’ private messages.

In Kenya, this digital crackdown has become increasingly localised and lethal. Following the "Gen Z" protest waves of 2024–2025, Amnesty International documented a coordinated system of tech-facilitated state violence. Reports estimate that security agencies leveraged digital data to carry out over 3,000 arbitrary arrests and 128 killings, while telecommunications giants faced allegations of sharing subscriber location data with clandestine police units without warrants.

Police used violence to stop the protesters during the protests in Kenya in 2024. Source: BBC

For women, the digital landscape is a minefield. A 2025 UN Women report reveals that 70 percent of female activists and journalists in the region have experienced online violence, with 42 percent of those cases escalating into offline physical harm. While on gendered surveillance, marginalised groups, particularly women, face a disproportionate impact. In Kenya, state-linked troll networks frequently use sexualized disinformation and AI-generated deepfakes to shame female leaders into silence.

The newly enacted Computer Misuse and Cyber-crimes (Amendment) Act, 2025, has been criticized by Human Rights Watch for vague provisions that effectively criminalize legitimate online expression under the guise of "combating misinformation."

The developer in the crosshairs

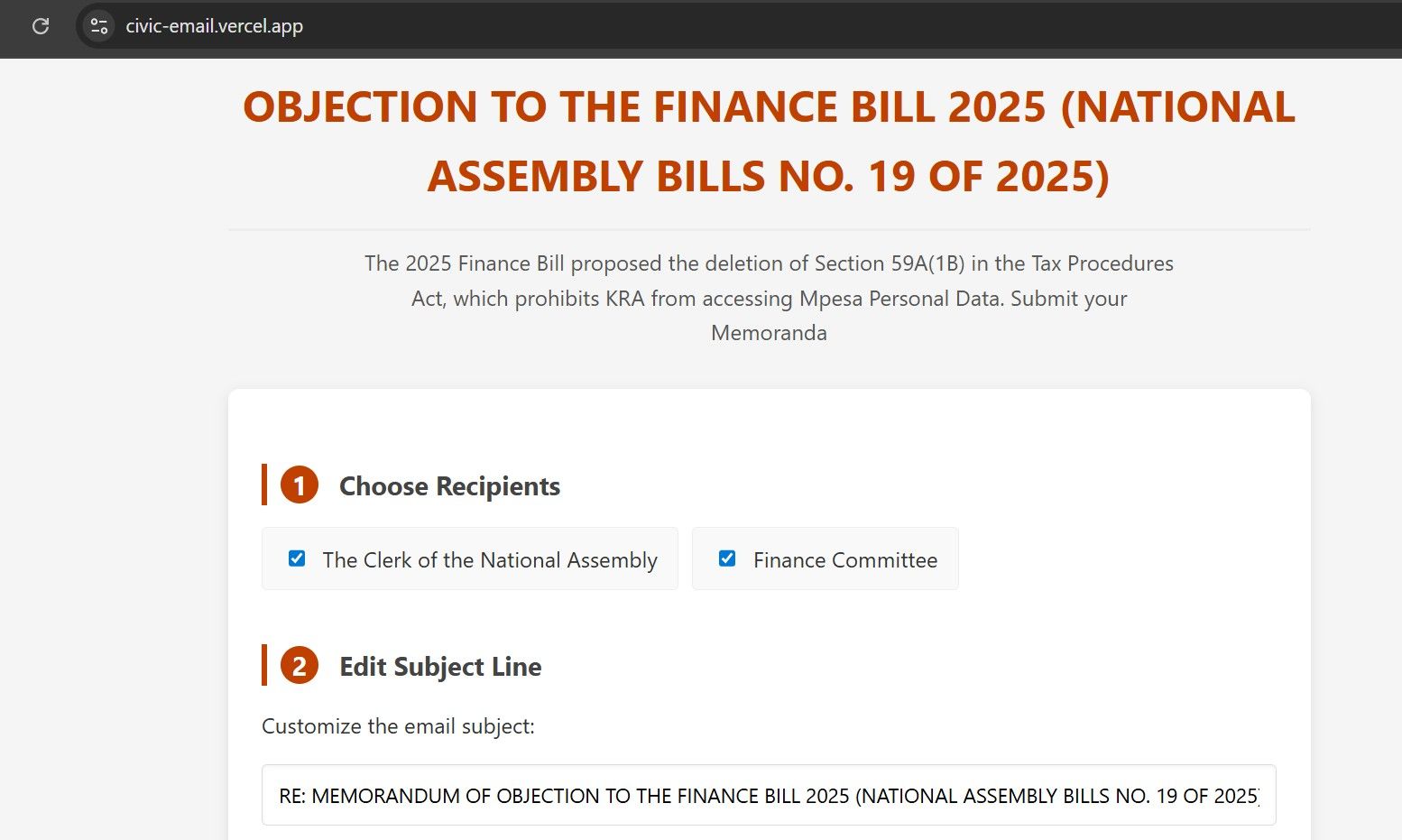

Kenyan software developer Rose Tuguru Njeri, 35, whose desire and commitment to "coding for the people" eventually put her in the crosshairs of the state, was shocked that the catalyst for her notoriety was a simple, yet powerful, open-source tool. “Mine was not original,” she explained, referencing a similar platform that existed during the 2024 Finance Bill discussions, which allowed people to send memoranda to selected government email addresses. In 2025, as a new Finance Bill was being debated, a post on Twitter lamented the lack of a similar platform. She took up the challenge immediately, recalling “I was like, yeah, I can do it. No problem. And I coded it in two hours.” The platform, aptly named 2025 Finance Bill Emailer, was a rapid, automated response to a cumbersome process.

A lawyer, Fidel Mwaki, had already drafted a memorandum rejecting the 2025 bill and placed it in a Google sheet. The process required citizens to manually copy the entire text, open their email, paste it, and send it.

“My process was to automate that,” Njeri said. Users simply navigated to the website, selected the designated recipients, the official emails provided by the finance committee, and could edit the pre-written subject and content. Clicking ‘send’ redirected the user to their own emailing platform, ensuring the memorandum was sent from their address and they signed as themselves. The site itself was technically uncomplicated: “a very simple HTML, JavaScript, CSS site. Just a static site. There are no animations”. Before her arrest, it had gathered about 5,000 views. “To me it was just something I did and I forgot about,” she recalled.

She realized the platform’s impact when she began receiving screenshots on X from people who had sent their memoranda. “It’s very user-friendly and people are actually sending emails to parliament,” she noted, acknowledging that her lack of a large social media following initially made her treat it as a small, successful project. Unbeknownst to her, while she went on with her life, she had landed on the government’s radar.

Friday evening arrests

During her interrogation, it became clear that the state had been surveilling her. They had initially attempted to track her via her smartphone, but her use of a VPN and a cleaning app meant they were blocked. Instead, they resorted to tracking her using her Kabambe, a Swahili term for a basic mobile phone, known for its durability and simple functions like calling and texting, popular in areas with limited access to internet or power.

“They used my Kabambe to triangulate,” she explained. She received strange, consecutive calls on both her personal and business lines on the feature phone. The surveillance extended far beyond phone tracking. The interrogators revealed a disturbing familiarity with her movements: “They were telling me, ‘we’ve been seeing you, you go to the shop, you take your kid to school’.”

They even knew the details of her weekend plans. She was detained on May 30, 2025, at an event celebrating her graduation from a business training course. The DCI officers told her, “We were not even sure you were going,” confirming they had been listening in on her calls to friends.

Every day, she held onto the belief that the police would realize the "silliness" of the situation and release her. It was not until Saturday, May 31, evening that her lawyers mentioned they would be calling a press conference.

On Sunday, June 1, 2025, approximately 30 to 50 key activists and family members led the physical storming of Pangani Police Station. While the physical numbers were modest, the presence of influential activists like Boniface Mwangi and Hanifa Adan ensured the event was live-streamed to millions.

The digital campaign was the engine of her release, designed to turn a "silent" weekend arrest into a national scandal. #FreeRoseNjeri was the primary tag, garnering nearly 1 million views within the first 48 hours. #RejectFinanceBill2025 was linked to her arrest hence the to the broader tax protests, activists ensured her story stayed at the top of the "Kenyans on X" feed.

The campaign reached international news outlets like The Guardian and BBC within days. This global pressure culminated in her being named to the TIME100 Next list later that year. The release wasn't just won on Twitter; it was secured by an unprecedented "barrage of lawyers" who volunteered their services to overwhelm the police station and the courts.

Njeri's case had high-level visibility with the former Chief Justice David Maraga and Senior Counsel and former Vice President Kalonzo Musyoka personally went to court. Their presence made it impossible for the police to continue holding her without a paper trail.

Veteran lawyer John Khaminwa and Senator Okiya Omtatah visited the police station including people like Juliani, Boniface, Hussein Khalid, and representatives from NGO's like TISA, LSK and Sophie Mugure of the Gen Z movement.

A female protester in downtown Nairobi. Source: AFP

Law Society of Kenya President, Faith Odhiambo, issued constant updates on social media, documenting every time lawyers were denied access. This created a legal record of constitutional violations. When she was finally arraigned, the legal team (including John Khaminwa and Eric Theuri) argued that the charge of "unauthorised interference" was absurd, as the government had invited public emails. Lawyers used her medical condition (anemia) to argue for immediate bail, eventually securing a Ksh 100,000 personal bond on June 3, 2025.

Amnesty International and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) estimated that between June 2024 and late 2025, there were at least 3,000 arbitrary arrests linked to nationwide demonstrations.

Amnesty International Report (November 2025) adds, "This fear, everyone is feeling it... Kenyan state authorities responded by violently cracking down on young people's exercise of their rights... through online intimidation, threats, and unlawful surveillance. [This creates] a chilling reminder of the shrinking space for dissent."

Law Society of Kenya’s "In Search of an Answer" Report (2025) reads, "Scores of Kenyans killed, hundreds maimed, and many more subjected to arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and trauma that will take generations to heal. It documents the wounds visible and invisible that continue to bleed long after the last protester fell silent."

When the time came to write her statement, and she was finally told the reason for her arrest was the email platform, she requested to write in her statement: “This is ridiculous”. Both officers laughed and refused. “They overreacted. They overreacted. It didn't make sense. It still doesn't make sense,” she stated. This feeling was validated when the judge ultimately threw out the case.

Milimani principal magistrate Geoffrey Onsarigo said the software developer did not commit any offence when she invited members of the public to volunteer views over the 2025/2026 Finance Bill. Onsarigo agreed with defence lawyers led by Senior Counsel Kalonzo Musyoka and former Chief Justice David Maraga that one cannot be charged for exercising a constitutional right.

The court said the charge against Njeri did not state whether there were any deaths occasioned by the invite to give their views on the Finance Bill. The 35-year-old was charged with unauthorized interference with a computer system. She was accused of creating a program that spammed email addresses of the House Finance Committee.

Njeri’s innovation was critical, but it was just one part of a decentralized, technologically-savvy resistance movement. Where the former anti-government protesters of previous eras might have relied solely on boots on the ground, this generation brought code to the streets.

Her arrest, initially meant to intimidate, became an unparalleled promotional campaign. It drew public attention to her other governance projects, including the ‘Insult Tracker,’ a simple site documenting the "ugly language" politicians used against the public in mid-2024.

Kenyans demonstrates rejection for the Finance Bill online and on the streets. Source: Africa Uncensored

Tracking ugly language

President William Ruto was tracked in digital rights "insult trackers" for a deeply chilling directive given to police: “Wapige risasi miguu aende hospitali akienda kotini” (Shoot them in the legs so they can go to the hospital as they go to court).

This normalization of state violence carries a grim weight when viewed alongside the case of Rex Masai, the first victim of the June 20, 2024 Gen Z protests. Rex was shot in the leg, a tactic presented by the President as "measured", but he bled to death before he could ever reach a hospital or a courtroom. This rhetoric suggests that wounding citizens is an acceptable strategy for control, ignoring the fatal reality that a "humane" shot to the leg is often a death sentence.

The violence was further codified on June 26, 2025, at Harambee House, when Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen issued a terrifying directive: "Na tumeambia polisi, mtu yeyote mwenye atakaribia police station, piga yeye risasi" (And we have told the police, anyone who approaches a police station, shoot them). This order effectively turned civic space into a "kill zone," reframing the constitutional right to protest as a capital offense and treating citizens not as stakeholders, but as enemy targets.

You can check out more in the Insult Tracker.

![]()

Screenshot from the Insult Tracker app.

A movement of coders

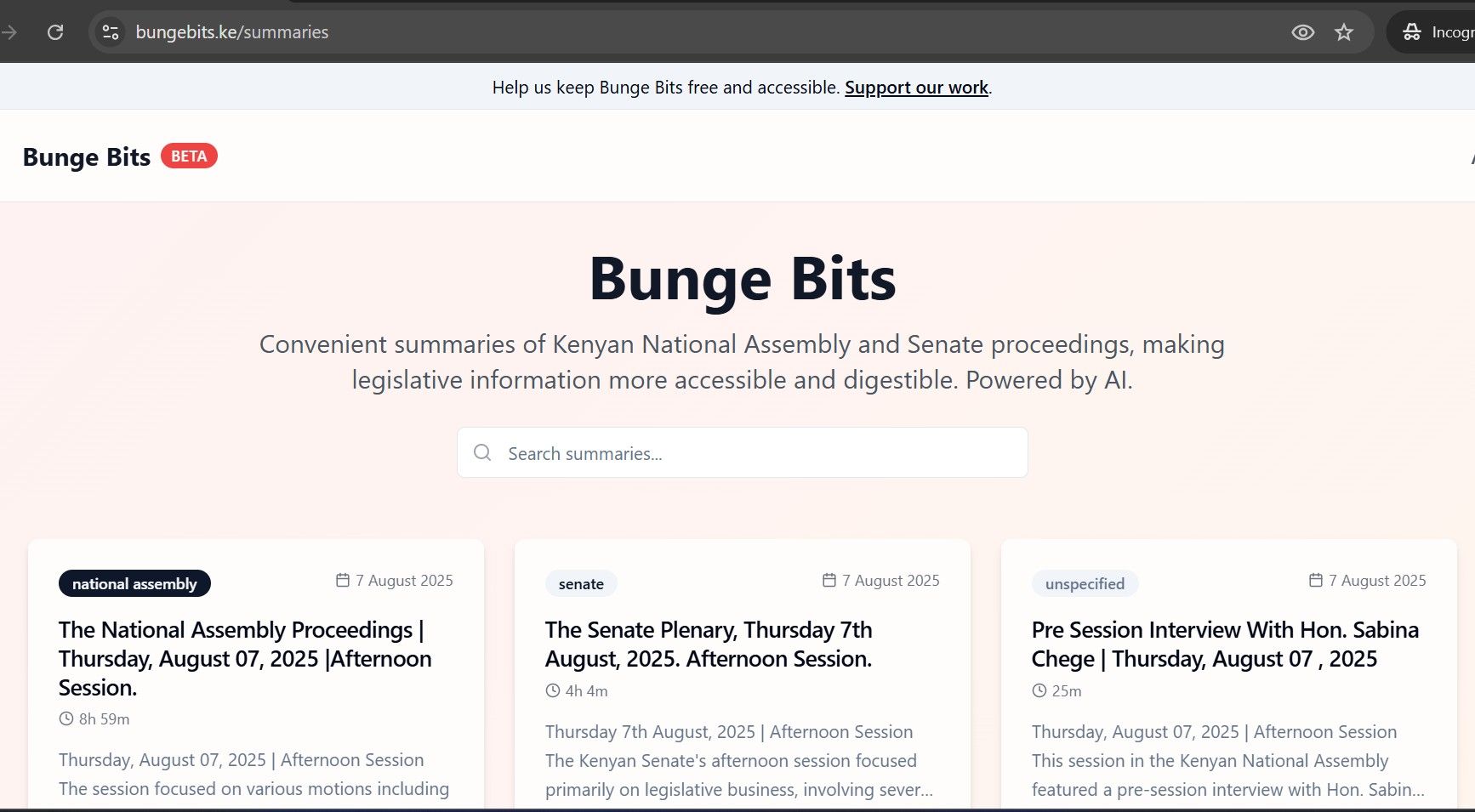

This accidental spotlight is a microcosm of a much broader technological awakening among Kenyan youth. Other Gen Z tech activists have rapidly advanced the agenda: a group known as Civic Education Kenya has attempted to map out IEBC polling stations to foster democratic accountability. Another developer, Collins Muriuki, created ‘AI Hansard,’ an artificial intelligence tool that summarizes and checks the statements made by politicians in Parliament.

Over the past two decades, citizens and tech professionals have shifted from passively consuming information to actively developing digital systems that protect human rights and democracy. Njeri explains that this confluence of tools creates new opportunities: “Basically, the opportunities to have people who are just ordinary citizens actually having their voices being heard.

The post-election violence of 2007–2008 marked the beginning of the Kenyan tradition of tech-activism. Rumors and state-sponsored narratives filled the information void left by the government's ban on live media broadcasts. Kenyan techies responded by creating Ushahidi (the Swahili word for testimony), an open-source platform that enabled people to report violent incidents and violations of human rights online and through SMS. The platform gave humanitarian responders a lifeline and the public a way to find safe routes by visualizing these reports on a real-time map. Tech has enabled that. It's up to us to be active citizens."

In the 2017 and 2022 General Elections, the focus shifted to "Parallel Voter Tabulation." To counter the historical mistrust in the official tallying process, tech-savvy citizens and civil society groups created election dashboards. Platforms like ELOG (Elections Observation Group) and citizen-led initiatives used OCR (Optical Character Recognition) and cloud databases to upload photos of Form 34As (the primary result forms at polling stations).

These platforms used data visualisation to present photos of Form 34A directly from polling stations. By making these forms searchable and aggregate-able by the public, techies effectively crowdsourced the audit of the election. This transparency acted as a check against "result doctoring," as any discrepancy between the physical form and the official portal could be flagged instantly by the online community.

The 2024 Gen Z protests marked a shift toward high-fidelity, live coordination. X Spaces emerged as a digital town hall, hosting massive audio conversations—some peaking at over 150,000 live listeners—where citizens debated the Finance Bill and organized logistics. Unlike traditional political rallies, these spaces were decentralized and leaderless, making them difficult for authorities to disrupt.

Using AI apps made by coders to protect themselves from the authority brutality.

To supplement this, protesters utilized Zello, a "push-to-talk" walkie-talkie app that allowed for rapid, low-bandwidth communication on the ground. This ensured that even when mobile data was throttled, protesters could coordinate movements and alert one another to safety risks in real-time.

Kenyan activists' use of security technology has increased along with the state's capacity for digital surveillance. VPN (Virtual Private Network) usage frequently increases during times of high political unrest as people try to get around internet outages or "shadow-banning" on social media.

Additionally, secure groups for legal and medical rapid-response teams have been made possible by the shift from unencrypted SMS to Signal and Telegram. These encrypted channels were essential for lawyers to monitor arrests during the 2024 protests and for "street medics" to find and tend to injured protestors without disclosing their coordinates to surveillance.

Violence and abductions

After the 2024 and 2025 protests young Kenyans who were vocal against the government online confronted a landscape of systemic violence and state-sanctioned abductions.

According to the LSK report, "In Search of an Answer" (2025), this period was marked by the re-emergence of "dawn raids" and the "barrel of a gun" being used to silence dissent against economic policies like the Finance Bill.

The scale of the crackdown was documented across several human rights frameworks. The Independent Medico-Legal Unit (IMLU), in its Gen Z Protests 2024 Report, highlighted a pattern of behavior where police used lethal and less-lethal weapons on unarmed protesters, recording over 100 photographs and 45 videos as forensic evidence of these violations. The report noted that 11 months after the initial June 2024 protests, no significant action had been taken against individual officers or commanders.

Parallel to the street violence, a surge in "enforced disappearances" became a primary state tactic. Amnesty International’s 2025 report, "This fear, everyone is feeling it," revealed that between 2024 and 2025, at least 83 people were victims of enforced disappearances, while 128 killings were recorded. Victims were often pulled into unmarked vehicles by masked, plain-clothes officers- a practice the KNCHR noted continued despite explicit court orders banning the use of unidentified police.

Citizens used social media to viralize footage of "unmarked cars" and "masked officers." This digital paper trail, as documented by IMLU, served as a critical tool for identifying perpetrators who attempted to hide behind anonymity.

Tech as a shield and a weapon

In response to this level of violence and to counter the "snatch-and-grab" tactics, software developers launched online panic buttons and live-location sharing tools. These allowed protesters to alert a network of lawyers and human rights defenders the moment they were targeted.

Claire Wangari Mwenda, a Bachelor of Pharmacy student took to X, to announce her own critical contribution: a panic button app. This innovation emerged against a terrifying backdrop of mounting anti-government protests, where young activists were increasingly vulnerable to being detained, disappearing, or being abducted by "unknown individuals" or security officers in unmarked vehicles.

Claire’s app, aptly named “Find Me,” is designed as an instant, pocket-sized SOS button. It allows users to share their real-time location with a single click. In scenarios where swift action is the only defense, that ability to broadcast one’s exact location can provide loved ones, legal teams, and human rights advocates with the crucial last known coordinates for intervention or investigation.

The true ingenuity of “Find Me,” however, lies in its design philosophy: it is engineered not to store any user data. In a country where surveillance is a major concern, this absence of a digital trail significantly reduces the risk of the app itself being weaponized against activists. Operating as a lightweight, serverless web app, it is a crucial "last mile" defense, focused entirely on simplicity and getting immediate help while minimizing the digital footprint.

Multiple attempts to secure an interview with the creator of the 'Find Me' app, via both email and social media, were unsuccessful.

You can check out the "find me" app here: wangarimwenda.github.io/find me/

Digital revolution

Kenyan tech-activists proved that digital proficiency can effectively neutralize state surveillance. Reports from Amnesty International, Media Council and Africa Uncensored describe a generation that didn't just use tech, but mastered it to stay steps ahead of a government attempting to "weaponize" telecommunications infrastructure.

The Africa Uncensored documentary, "Invisible Eyes" (2025), takes a harrowing look inside the state's surveillance apparatus. It asks the critical question: "What happens when state surveillance is used on a nation's citizens to restrict their freedom?". The film highlights how the state allegedly tracked and abducted dozens of young Kenyans using sophisticated digital footprints. However, it also showcases the tech community's counter-response: identifying unmarked vehicles through crowdsourced data and forensic digital mapping to prove that abductions were systematic, not random.

The Media Council's report captures the sheer "resourcefulness of the movement." It outlines how techies out-maneuvered state interference through deliberate technical choices.

Recognizing that cellular networks could be throttled or monitored, protesters shifted to Zello, a walkie-talkie app. This ensured "secure and continuous communication" when standard mobile data was under threat. The report notes that the widespread use of VPNs (Virtual Private Networks) became a standard digital hygiene practice, allowing protesters to bypass internet disruptions and protect their identities.

Gen Z protests shakes Kenya. Source: AFP

Why it matters

For Njeri, the involvement of women in tech-activism is not just about technical skill; it is also a definitive battleground for human rights. She argues that in formulating policy, if women, who are "literally half the population", are not considered, then "there is a lot that is left out." Women bring to the table a crucial perspective on social justice and governance issues, making their active involvement essential.

Njeri who was named as part of the TIME 100 NEXT at an gala event on October 30, 2025 in New York says her advice to young women who want to develop technical skills for social and political change is unequivocal: "Go for it. Upskill and don’t be shy."

The narrative of Kenyan women in technology has shifted from basic inclusion to high-stakes upskilling and digital resilience. Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) shows significant progress in how women navigate the digital and economic world. At 40.6 percent, women in Kenya are now considered "empowered" in 2025, up from 29.3 percent in 2020.

Empowerment is highest among the 18–24 age bracket (48 percent), reflecting the "Gen Z" shift toward digital-first activism and careers.

According to the LSK e-Advocate (March 2025) in the article "Aluta Continua: Digital Activism, Feminist Resistance, and the Fight Against Femicide in Kenya," this new era of "feminist tech-resistance" has seen women leverage digital platforms to bypass traditional gatekeepers and confront systemic injustice with unprecedented transparency.

This movement represents more than just social media usage; it is a sophisticated adoption of technology to safeguard democratic participation and bodily autonomy. Women-led organizations like FIDA-Kenya have documented that this resistance has emerged as a direct counter-response to the "gendered digital repression" used to silence women’s voices in public discourse.

FIDA-Kenya’s 2025 reports, including "FIDA Kenya Charts a Path to Digital Justice," emphasizes that the "digital revolution" has created new frontiers for violence (such as deepfakes and coordinated troll attacks) but also new avenues for justice. “Women must not have to choose between engaging in the digital age and safeguarding their safety. They deserve both.” (FIDA Kenya, 2025).

Young Kenyans drove the protests across the country. Source: Katie G. Nelson

The legislative battleground

FIDA calls for a roadmap where technology is safe and inclusive, demanding that legal frameworks like the Computer Misuse and Cyber-crimes Act be updated to recognize the specific lived realities of technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV). The culmination of this activism comes face-to-face with the law itself. Njeri, a victim of previous cyber crime laws, has strong views on the newly proposed Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act, 2025.

While she acknowledges that some of the amendments are "legit", like those targeting child pornography, pedophilia, and tangible online harassment, she is vehemently against the vague language in other sections.

She points specifically to the amendments on Cyber Harassment (Section 27), which criminalize online messages that are "likely to cause them to commit suicide," a charge that carries a penalty of up to KSh20 million or ten years in prison. While seemingly protective, activists argue the standard is "subjective and speculative," failing the legal test for clarity and potentially being used to criminalize harsh but legitimate criticism of public figures.

"How do you quantify, how do you prove that you made me suicidal because you said I look like this?" Njeri asks. The law, she argues, is too vague and open to political abuse. "Knowing the government of the day, they will definitely abuse those vague clauses, and that's what we are rejecting... The things that they want to use to put people in the same situation I was in, those ones we reject."

The Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes (Amendment) Act, 2025, contains several provisions that have raised significant concerns among women activists, human rights defenders, and digital rights organizations. While the government frames these changes as necessary for national security and protection against fraud, activists fear they could be weaponized to silence dissent, restrict civic engagement, and target those who use digital platforms for advocacy.

Another clause is Section 6 that grants the National Computer and Cybercrimes Coordination Committee (NC4) administrative power to issue directives to render a website or application inaccessible if it is "proved" to promote "unlawful activities," "terrorism," or "religious extremism". Activists fear this lacks sufficient judicial oversight and could lead to the arbitrary blocking of platforms used for organizing protests or reporting on human rights abuses.

Section 30 the Offensive or Menacing Messages clause, this amendment broadens existing laws to include emails and phone calls, not just social media or text messages. Human rights groups warn this could be used to harass citizens or activists who use direct communication to hold elected officials accountable or express dissent.

A new Section 46A on Content Takedown Powers introduces a court-ordered process for shutting down websites or digital devices used for "unlawful activities," the broad definition of such activities remains a point of concern for those who fear judicial overreach.

Multiple civil society and religious organizations have formally challenged or criticized the law. KHRC argues the law violates constitutional rights to privacy, free expression, and access to information. They filed a successful petition to temporarily suspend Section 27.

ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa warns that vague terminology fails international legality requirements and lacks judicial oversight for platform blocking. They filed a joint constitutional petition and submitted formal memoranda to Parliament.

Bloggers Association of Kenya (BAKE) states the Act creates an "unacceptable threat" to digital rights and was passed without adequate public participation. While Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet) voiced concerns about granting officials power to block websites, which could damage Kenya's open digital environment.

Although this type of activism is difficult—marked by surveillance, "Friday arrests," and state-linked online harassment—it has proven effective for three reasons. By moving activism to the web, the movement became "leaderless and tribeless," making it harder for the state to stop it by targeting just one person. Secondly, technology like AI chatbots was used to translate the Finance Bill into local languages, ensuring policy was no longer "gatekept" by the ruling elite. And finally, Njeri’s tool proved that a single coder can amplify the voices of millions more effectively.