The human eye has always been our gateway to the world, the our first window to reality, the lens through which our understanding of perception and meaning took shape. This intimate dialogue between sight and memory gave birth to what we call “visual memory,” a realm that once began as fleeting impressions but gradually blossomed into a rich, interconnected archive, evolving hand in hand with the currents of civilization and the leaps of technology.

Today, in the age of digital transformation, visual memory is no longer the sole domain of the human eye. Algorithms have stepped in as unseen curators and archivists, sifting, selecting, and cataloging the imagery of our lives. This exploration traces the journey from natural memory to its digital counterpart, reflecting on how technology reshapes our notions of preservation, archiving, and the very ways we see and represent the world.

By Leonardo da Vinci (1955), Das Lebensbild eines Genies, Emil Vollmer Verlag, Wiesbaden/Berlin. Documentation of the Da Vinci Exhibition in Milan, 1938. Cited in Hans-Werner Hunziker, Im Auge des Lesers, Zurich, 2006. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Visual Memory: From Sensory Experience to Symbolic Representation

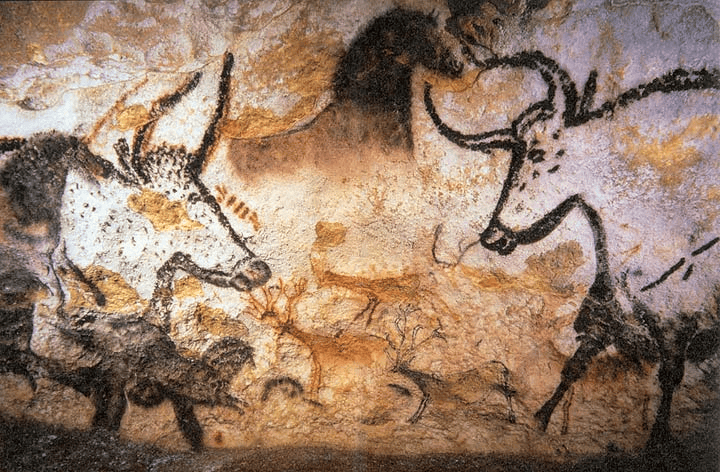

In the beginning, the primitive drawings on the walls of the Lascaux and Chauvet caves were more than mere artworks, they were the first attempts at creating a collective visual archive. These drawings embodied humanity’s innate desire to document sensory experiences within its environment, leaving behind a testimony of moments lived by both individuals and communities.

Humans employed these drawings to immortalize rituals, hunting practices, and beliefs, and through them, visual memory began to take on a tangible form. It was not merely a record of personal recollections, but a shared means of constructing meaning.

By EU – Personal work, public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Over the ages, this visual documentation evolved and diversified. It began with the religious murals of the Middle Ages, painted in churches and monasteries, serving as the collective memory for illiterate people. Painting was used to tell stories from the holy books, to frame images of heaven and hell, and to instill values and behaviors. At this stage, visual memory was governed by religious institutions, fulfilling an educational and spiritual role while shaping collective imagination according to theological authority.

Then, during the Renaissance, the equation changed. With the development of drawing tools and perspective techniques, and the rise of Humanism, visual memory began to free itself from purely religious frameworks. Portraits emerged as instruments of personal documentation, not merely symbols. Images began to represent the individual, their identity, social class, and even aspirations. In this context, humans started to craft their own visual memory, immortalizing themselves as subjects of reflection, not just as symbols of doctrine.

Once again, with the Industrial Revolution, the scales tipped anew. Photography emerged as a revolutionary tool, a machine that could preserve the moment with apparent precision and objectivity. This transformation was not only technical but philosophical: the image no longer required a painter’s hand; it could be produced with the simple press of a button.

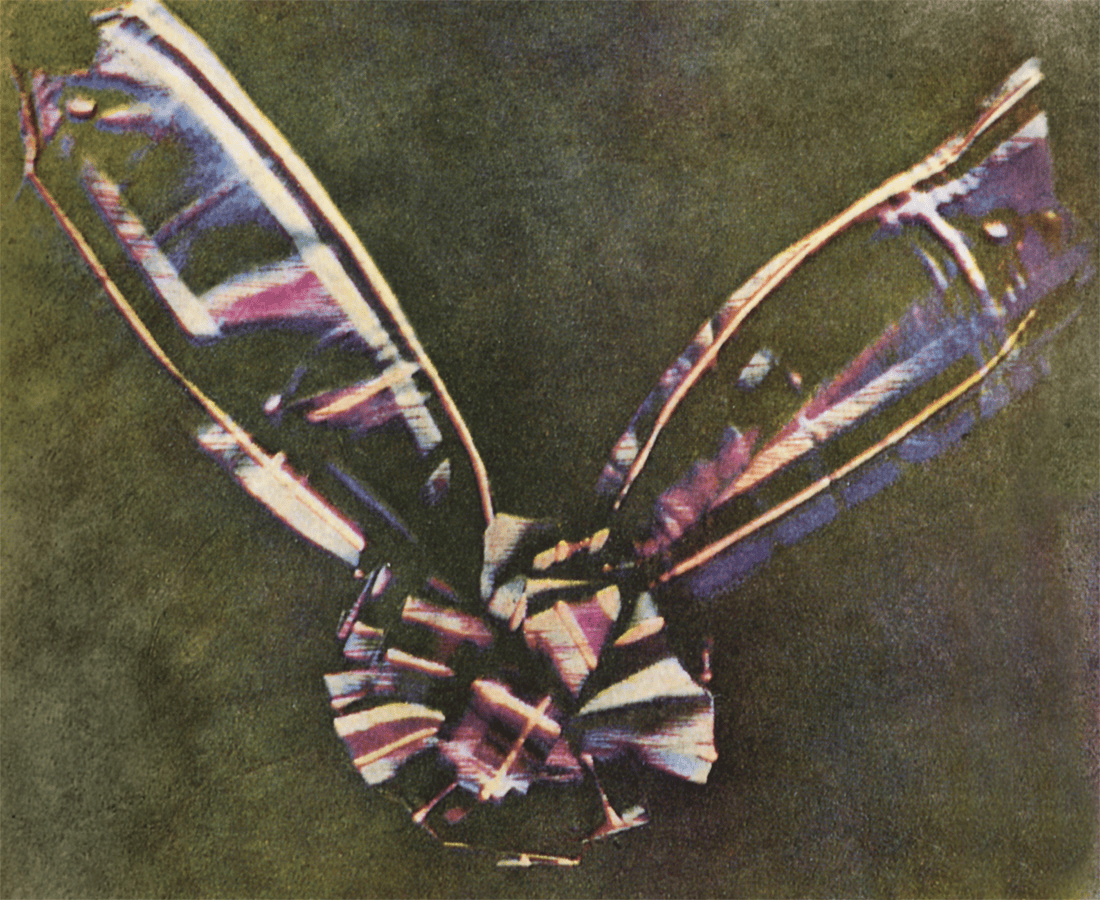

First color photograph in history, 1861. By James Clerk Maxwell – Scanned from The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Jack H. Coote, 1993. ISBN 0-86343-380-4. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons

At this stage, visual memory shifted from individual creation to rapid collective archiving. Images of factories, workers, streets, and political events became raw material for collective consciousness, a source for crafting alternative narratives beyond the official story.

Across all these transformations, one thing remains clear: visual memory changes according to who controls the tools of its production. In the Middle Ages, it was the Church. During the Renaissance, it was the elite. And with the Industrial Revolution, new actors emerged: the working classes, the press, and the modern state.

From Material to Data: Technology and the Transformations of Archiving

The digital age marks a pivotal turning point in the history of visual memory. Smart devices have become everyday archival tools, capturing moments through photos and videos at the press of a button. Beyond this, algorithms have entered the process, sorting, classifying, and even suggesting what should be saved or shared.

With the expansion of platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and other social media, visual memory has shifted from being solely a personal experience to a shared digital memory, where individual and collective contexts intertwine.

Yet this evolution is not without challenges. Digital memory, despite its precision and accessibility, raises ethical and political questions concerning content ownership, cultural biases embedded in algorithms, and the control over what is displayed and what is forgotten.

The Visual Archive: Between Authority and Representation

Today, visual archiving is presented as a field of struggle between epistemic dominance and attempts at cultural resistance. The archive is far from neutral; what is preserved, or ignored, carries an ideological weight. Exhibitions in major museums and institutions often reflect the narratives of dominant powers while marginalizing local experiences and the histories of underrepresented communities.

In response, resistance projects have emerged, aiming to recover forgotten narratives through community archiving or the creation of alternative digital museums. These initiatives, particularly in contexts of diaspora or conflict, contribute to preserving collective memory outside institutional frameworks.

Such resistance archives serve as tools for rewriting history collaboratively, restoring visibility to stories excluded from the official record. Here, technology, though often employed by dominant institutions, can become in the hands of marginalized communities a means of reclaiming their memory.

A striking example of what global platforms can offer comes from Google’s 2022 interactive digital experience exploring the pyramids of Meroe, the last capital of the Kushite Kingdom, as part of the Google Arts & Culture program in collaboration with UNESCO. What distinguishes this project is not only the use of virtual tours and high-resolution panoramic images but also the integration of narrative and poetic dimensions through a poem by Sudanese-American poet Emi Mahmoud, alongside historical information about the kings and queens of the Kushite civilization.

This experience exemplifies the potential of digital institutional platforms for accessibility, especially given the scarcity of high-quality visual documentation of Sudanese historical sites online. At the same time, it raises critical questions: Who owns the narrative? Who has the right to represent memory? While this platform provides global access to the pyramids, it remains largely outside the control of local communities, the natural custodians of that memory. This opens a critical discussion on digital colonialism and the reproduction of memory in supra-local contexts.

Despite the enormous potential of digital archiving, there is an inherent fragility threatening the survival of these data. Files can deteriorate due to technical failures, software updates, or even the loss of supported formats, underscoring the urgent need for secure digital infrastructure.

Alongside these challenges are legal and ethical questions regarding digital ownership: Who owns an image? Who has the right to archive it? Are the contributors to visual memory recognized? How can fair mechanisms be established to protect rights? In this context, blockchain technology offers potential solutions through mechanisms of traceability and contractual ownership.

The question of the right to document remains pressing: Do individuals and communities have full freedom to record their memory? What are the limits of censorship or restriction? How can we protect voices striving to preserve their narratives from being excluded or silenced?

In my research on the role of technology in visual documentation and cultural memory preservation, I interviewed Mohamed Dafallah, a Sudanese multidisciplinary visual artist working at the intersection of expressive abstract digital art and cultural activism. His works address political and social themes through visual symbols and abstractions inspired by Sudanese realities and personal experiences, presented as visual platforms for awareness and resistance.

Dafallah is known for his innovative use of technologies such as blockchain and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) as tools for documentation and archiving, not merely for sale or exhibition, giving his works multiple dimensions simultaneously. He has participated in NFT.NYC in New York City, one of the world’s leading gatherings celebrating blockchain art and technology, where he showcased works highlighting the Sudanese experience in a global context.

Mohamed Dafallah at NFT.NYC 2024. Source: Mohamed Dafallah

Personal Experience with Technology in Documentation and Archiving

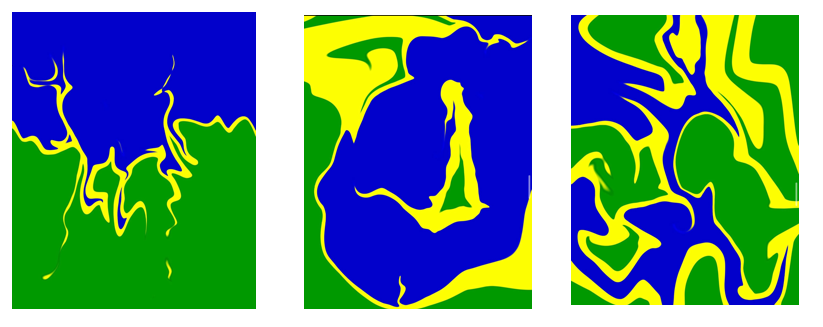

In the interview, Dafallah discussed his experience using NFTs and blockchain as alternative means of visual documentation. He explained how he documented the events of the October 25, 2021 coup in Sudan through artworks published as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) on decentralized platforms, specifically OpenSea platform.

These works, collectively known as Sudanese NFTs, included slogans, figures, and symbols expressing anti-coup messages and reinforcing the spirit and goals of the December Revolution, such as 'Al-redda mostahela' “Retrogression is Impossible” and “Freedom, Peace, and Justice.” They highlighted crimes and violations against civilians while also emphasizing the resilience of the Sudanese public in the face of repression.

© All rights reserved by the artist Mohamed Dafallah

In another experiment, Dafallah used the same technology for intellectual property protection. He preserved the concept of an ongoing art project by converting it into a digital work recorded on the blockchain, turning the technology into a legal and artistic tool for safeguarding rights, rather than using it solely as a platform for buying and selling, as is commonly done.

Regarding the reliability of blockchain and NFTs, Dafallah considers these digital mediums to be relatively secure, particularly due to their decentralized nature. There is no central authority controlling the network or servers; instead, every participant in the network acts as a partner in its management and protection, reducing the risk of manipulation or exclusion. He noted that the greatest danger in centralized networks lies in the possibility of one party controlling 51% of the servers, granting them authority over the network, potentially blocking access or adding data, whereas crypto-based technologies avoid this vulnerability due to their decentralized structure.

Despite the innovative solutions offered by technology, Dafallah emphasizes that relying solely on digital platforms is insufficient. He stresses the need for balance between traditional and digital archives, citing his experience at Omdurman Ahlia University, which once housed one of Sudan’s largest student research libraries, containing thousands of studies. This library was completely destroyed during the 2023 war in Sudan, resulting in a massive loss of knowledge and cultural heritage. Dafallah believes that a parallel digital archive could have mitigated these losses or preserved part of the content for future generations, underscoring the importance of integrating both systems to build robust archival frameworks that safeguard both individual and collective memory.

Reshaping Memory: Augmented Reality and Expanding Visual Perception

Technologies such as augmented reality (AR) offer a new dimension to visual memory by integrating digital elements into the real world, creating an interactive and immersive experience. In the artistic context, AR allows visitors to engage with artworks in a personal and unique way, adding new layers of meaning.

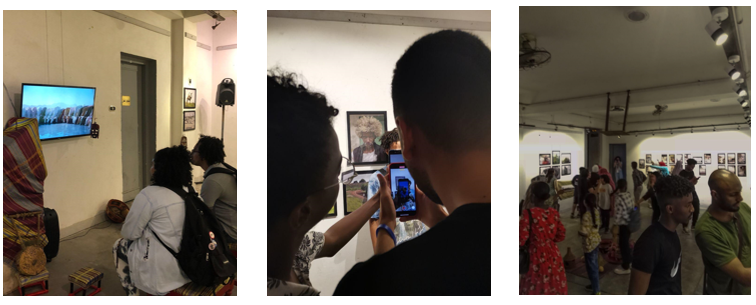

From my personal experience, I find that when technology is used with conscious design, it transforms into a poetic instrument that goes beyond mere documentation, becoming a tool for visually and emotionally reconstructing narratives. This approach was embodied in my first exhibition, “+249”, held in June 2022 at the Jesuit Cultural Center in Alexandria. The exhibition aimed to document everyday life in multiple Sudanese cities, Khartoum, Al-Gedaref, Port Sudan, and Wad Madani, through the lens of four Sudanese photographers: Abdelaziz, Mujahid Abu Al-Qasim, Ammar Abdullah, and Mohamed Babiker, who shared their personal archives with me.

Hadi Bakhit's first exhibition (249+) held in Alexandria.

However, the documentation wasn't merely a presentation of a visual archive. Augmented reality (AR) was incorporated to deepen the viewing experience, overlaying digital layers that added temporal and narrative dimensions to the images.

In the design, I focused on reconstructing the story behind each image and integrating musical cues connected to the social and cultural context, in collaboration with music producer Zaher “Taz Waves”. The exhibition also featured the film “Deal Nahna w Da al-Sudan” by director Mohamed Kordofani, creating a fully immersive audio-visual artwork that serves as a contemplative space for reflection.

Visitor reactions to the exhibition, particularly from non-Sudanese attendees, demonstrated the ability of this technology to convey a deep sense of the Sudanese experience, fostering emotional connections with moments and cultures that may be geographically distant yet strongly present through the digital medium. Notably, the integration of augmented reality (AR) was not merely a “technical experiment”; it was employed within a conceptual framework linking personal archives with collective memory, placing the viewer in a state of active participation with the content.

This interplay between the real and the virtual reshapes our understanding of “preservation” and “representation,” expanding the archive from mere storage to the ongoing reinterpretation and generation of meaning.

In conclusion, visual memory is not simply a record of what we see; it is a cultural, technological, and cognitive act that constantly renews itself. As reliance on technology for preserving memories grows, there is an urgent need for critical reflection on archival tools: who controls them, how to ensure plural narratives, and how to represent everyone.

The central challenge doesn't lie in technology itself, but in the policies that govern it, and in our ability to use it as a tool for justice, not domination. Visual documentation in Sudan cannot be separated from its political and social contexts, and technological use should not be read as merely a technical act, but as a simultaneous political and aesthetic choice. From individual experiments to global projects, from open platforms to decentralized networks, the need for a new hybrid archival architecture becomes clear, one that integrates the material and the digital, the local and the global, the present and the past.

Between augmented reality, blockchain, and other technologies, a network of scattered experiments emerges, signaling the birth of a new archival consciousness. In this vision, the image and the data are more than documentation, they are acts of resistance against erasure, reclamation of place and memory, and the right to narrate the story. Between the eye and the algorithm, memory remains in formation, waiting for those who will narrate it, preserve it, and continually rewrite it.