Trigger Warning and Disclaimer: The following content includes sensitive experiences. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of Andariya. We encourage you to engage with the piece in whatever way feels right for you. You can read our full editorial notice here.

Introduction

In East Africa, women’s issues intersect with politics, conflict, and state-building, revealing a complex reality that challenges women’s rights daily. From Sudan to Kenya, Uganda, and Eritrea, feminism has not been merely an elite discourse or foreign import; it has emerged as a living experience in the streets, camps, and diaspora spaces, where women have shaped diverse forms of resistance.

This article presents a Sudanese perspective on the feminist movement in the region, tracing the intersections of gender with race, class, and political affiliation, and analyzing how these intersections have driven feminist activism. Focusing on four main themes: forms of mobilization, the relationship with the state and law, the impact of conflicts, and feminist diplomacy in the diaspora, it uncovers commonalities and lessons from East African experiences.

Colonial and Postcolonial Feminism

Sudan: Early Beginnings and Ongoing Challenges

The feminist movement in Sudan began early, linked to the struggle against colonialism, and continued through subsequent national governments and multiple military coups. Since the early 20th century, Sudanese women have bravely fought for their rights.

Sudan’s feminist movement was closely tied to modernization and education initiatives. Pioneers such as Nafisa Ahmed Ibrahim, Aziza Maki, Hajja Kashif, and Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim helped establish the Sudanese Women’s Union in 1952, one of the most prominent feminist organizations in Africa and the Middle East. The Union played a key role in education, labor issues, and opposition to restrictive laws on women. However, this progress faced setbacks under military regimes, particularly after the September 1983 laws and the Public Order laws during the Inqaz regime (1989–2019).

A photo showing Sudanese women participating in the 1956 independence marches, wearing traditional Sudanese Toub, reflecting their active role in the national struggle. Source: Al-Majalla Magazine

During periods of popular revolution (October 1964, April 1985, December 2019), women participated actively, leading revolutionary work and resistance as part of what became known as the “Kandakas” of the Sudanese revolution. Their involvement marked a shift of the Sudanese feminist movement from an urban elite focus to a popular, cross-class movement.

Kenya: Between the Independence Movement and Environmental Activism

In Kenya, the early feminist movement was closely linked to the struggle against British colonialism. Women played significant roles in the Mau Mau War, yet faced political marginalization after independence. In the 1970s and 1980s, Wangari Maathai emerged as an ecofeminist icon, who founded the “Green Belt Movement,” which combined women’s rights with environmental protection and democracy. This experience offers a model of how feminist activism can move beyond narrow “women’s issues” to advocate for broader societal concerns.

Women's rights activists leading protests calling for an end to femicides in Kenya. Source: Reuters

Uganda: From Internal Conflicts to Women’s Initiatives

In Uganda, feminism was shaped by intersections of military dictatorship, civil wars, and the rise of armed groups such as the Lord’s Resistance Army. Despite these challenges, women established community support networks, particularly for survivors of sexual violence and war. In the 1990s, a quota system was introduced to ensure greater female representation in parliament. While controversial, seen by some as symbolic empowerment and by others as a way to domesticate feminist discourse, it contributed some legal progress, including combating discrimination and promoting equal treatment and empowerment for women and girls.

Eritrean Women: A History of Struggle and Continued Hardship

Eritrea offers a unique experience, with women playing a central role in the liberation struggle against Ethiopia (1961–1991). Women fought on the frontlines, making up nearly one-third of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front fighters. After independence, they faced the challenge of reintegrating these gains into a traditional patriarchal society under a centralized authoritarian state that allowed little autonomy for the feminist movement.

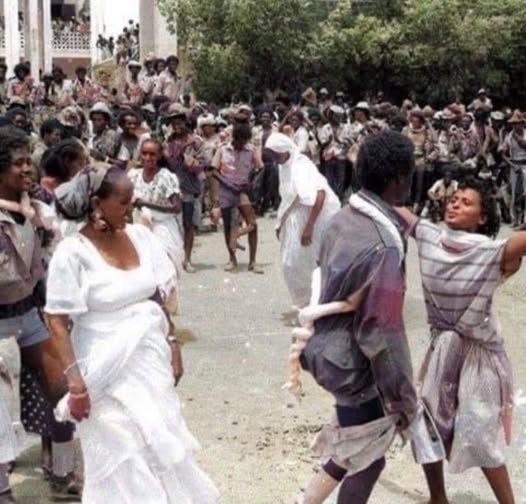

Eritrean women welcome freedom fighters in May 1991. Source: Black Region Facebook page

This diverse historical context underscores a painful truth: women in East Africa have paid the price for independence and fought for dignity and freedom. Yet, to varying degrees, governments and ruling regimes have disregarded these struggles. Women continue to resist, often at enormous personal cost, including displacement, homelessness, and violations of fundamental rights, including the right to life, due to the absence of institutionalized justice, law, and equal rights.

Forms of Women’s Mobilization and Political Participation

Feminist mobilization in East Africa has taken diverse paths. Sudanese women played notable roles in opposing the first military rule, with the Sudanese Women’s Union playing a key part in the October 1964 Revolution. The Union mobilized women to participate in protests led by its then-chair, the prominent activist Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim. After the revolution’s victory, the fall of Abboud’s regime, and the restoration of the constitutional process, Sudanese women achieved significant gains, most importantly the right to vote and run for office. In the first elections following the October Revolution, Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim became the first female parliamentarian in Sudan and the Middle East.

Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim, one of Sudan’s pioneering feminist leaders, receives the Ibn Rushd Prize for Freedom of Thought at the Goethe Institute in Berlin in 2006. Source: The Guardian

Grassroots movements also emerged, from resistance committees to community initiatives such as “No to the Oppression of Women,” and projects targeting the most vulnerable women, like tea ladies, exemplified by the “Kafteera” initiative. These forms differ from internationally funded organizations, which often operate with a globalized discourse disconnected from the concerns of women in impoverished neighborhoods and displacement camps.

The Sudanese experience highlights a key advantage: the effectiveness of a feminist movement is not determined solely by access to official institutions or international donors, but by its connection to grassroots social structures. The Sudanese feminist movement’s deep roots in society enabled it to rebound strongly whenever a ruling regime sought to control or suppress it.

For example, the ruling People’s Front in Asmara controlled the Eritrean Women’s Union and made it a state front, but this did not happen with the Sudanese Women’s Union, even after it was dissolved by Jaafar Nimeiri, because it was not a hierarchical elite body easily directed or eliminated. Instead, it helped form a horizontal popular base across Sudan, which could organize flexibly in response to risks and challenges. Consequently, all military regimes failed to control feminist bodies, which often contributed to undermining dictatorial systems through protests and peaceful activism.

Relationship with the State, Law, and Social Issues

The relationship with the state represents one of the most complex challenges for feminist movements in East Africa. In her book Politics and Gender in Sudan, gender studies expert Professor Sandra Hill examined the intersections of gender and the state in shaping policy and national identity, raising questions about the mechanisms used by the state, political parties, and religious groups to direct feminist activism according to specific cultural and ideological frameworks.

Sudanese women during the 2019 protests. Source: GNA

Sudanese women have contributed actively to political life both before and after Sudan’s independence in 1956. They opposed all forms of oppression through various means, including participating in public gatherings and protests, providing financial, media, medical, and legal support, and engaging in civil society activities.

At the same time, women faced legal restrictions, such as the Public Order Law, a symbol of women’s oppression, which was repealed in 2019. However, personal status laws still impose guardianship over women in marriage, divorce, and inheritance (See Sudan Public Order Law is Still Intact by SIHA). Women participating in protests, rights campaigns, social services, legal aid, journalism, and other public activities have faced a range of violations, operating in a broader context of gender inequality that complicates their activism.

In Kenya, women have also struggled against restrictive laws, though they contributed to constitutional reforms in the 2010 Constitution that enhanced women’s rights. Nevertheless, customary practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) remain widespread.

In Uganda, the parliamentary quota for women was an interesting experiment, but was often criticized as a mechanism for reproducing power rather than as a liberatory tool. In Eritrea, women’s influence on legislation protecting women’s dignity has been limited due to the political context. Despite women’s participation in the liberation struggle with the People’s Front, the ruling party today, the state remained centralized after independence, controlling feminist discourse and preventing its independence.

With the existence of the National Union of Eritrean Women, established in the 1970s, which helped draft laws granting women 30% of the seats in national and regional councils, while also allowing them to compete with men for the remaining 70%, its actual impact remains very limited when compared to the real challenges facing Eritrean women in education, employment, and dignity, such as protection from forced conscription, for instance.

This limited effectiveness has affected its independence as a feminist body. It never played a role similar to that of the Sudanese Women’s Union, which actively opposed military regimes and influenced the fall of entire systems, or contributed to drafting and amending laws supporting women’s rights and dignity.

Eritrean women fighters from the Eritrean People's Liberation Front, circa 1970s. Source: Reddit

Even though the Sudanese Women’s Union itself was not immune to pragmatic intersections with certain political forces and the pressures of Nimeiri’s regime, it nonetheless managed to preserve a degree of independence.

From a postcolonial perspective, one could argue that the post-independence state in East Africa largely reproduced patriarchal forms of control, sometimes through modern legal mechanisms, and at other times through alliances with tradition and religion. Yet, the roles, influence, and experiences of women have varied from one country to another, depending on their unique political and social contexts. To truly understand any experience, it must be studied within its cultural, social, and political context.

How have wars and conflicts reshaped women’s roles in East Africa?

First: Gender-Based Violence (GBV): I posed this question to Kenyan human rights lawyer Shelley Nyonje during a phone interview. She recalled vivid memories of violence against women in Kenya, saying: “During conflicts, women and children bear the heaviest burdens. The post-election violence of 2007 left women with destroyed homes, looted property and businesses, and the deep trauma of sexual violence. Yet, these women were courageous enough to launch empowerment initiatives. The effects of sexual violence are still present, but these brave women continue to fight in court and demand justice.”

Kenyan lawyer and activist Shelley Nyonje: Source Shelley Nyonje .

In Sudan, particularly in Darfur and South Kordofan, women have played dual roles: as victims of sexual violence and as activists building support networks within displacement camps, participating in emergency response groups, and later becoming advocates for women’s and human rights more broadly.

In my interview with Najda Mansour Adam, a Sudanese translator and journalist who is also a member of the Higher Committee for the Implementation of the Juba Peace Agreement (2020), she added: “Women in East Africa, in general, have benefited from the opportunities they fought to seize and have made significant personal progress. But I’ve noticed that Sudanese women, in particular, are distinguished by their collective sense of responsibility and their focus on the broader public good. I recall, for instance, how women took on the burden of problem-solving in the harshest conditions, like in the experience of the Qawmat Banat Al-Fashir (The Uprising of the Girls of Al-Fashir).”

According to a UN Women report released in April 2025, the number of people at risk of gender-based violence in Sudan has tripled, reaching 12.1 million. Although conflict-related sexual violence remains vastly underreported, evidence points to its systematic use as a weapon of war.

Recent reports also indicate that Uganda records the highest rates of gender-based violence across East, Central, and West Africa, reflecting profound and long-standing challenges faced by women and girls from an early age. Data shows that nearly 60% of girls and young women aged 13 to 24 have experienced one or more forms of violence during childhood, leaving lasting effects on their psychological and physical health as well as their ability to participate fully in social and political life.

The report also revealed that around 72% of Ugandan youth aged 18 to 24 had experienced at least one form of violence before the age of 18, indicating that violence is not limited to women alone, but also affects young people, thereby influencing the dynamics of families and society as a whole.

It further stated that about 25% of young women in East Africa consider physical violence from husbands to be sometimes justified, based on prevailing social norms and traditions, highlighting the role of cultural values in perpetuating patterns of violence.

These figures make it clear that addressing gender-based violence (GBV) cannot rely solely on legal frameworks. It also requires cultural and societal change, including awareness-raising about women’s rights, promoting gender equality within families and communities, and encouraging young people to adopt attitudes rooted in mutual respect and equality.

This context also underscores the importance of psychosocial support programs for survivors, as well as strengthening the capacity of local and international organizations to document violations and challenge harmful social norms that justify violence.

Second: Displacement and Refuge: During conflicts and wars in East Africa, women have emerged as key agents in rebuilding communities and taking on multiple responsibilities in the absence of men.

According to a Ugandan activist, despite the hardships of displacement and violence, women established economic empowerment initiatives to support their families and local communities. They also leveraged diaspora support networks to pressure decision-makers and push for legal reforms.

Ugandan activist Winnie Adeleye: Source Winnie Adeleye

In Sudan, journalist Najda Mansour shared her experience working with national organizations and local associations such as the Child Care Association in Kosti, where women launched income-generating projects and feminist awareness campaigns. These initiatives enabled women to participate in economic and political life even under harsh conditions.

From a legal and social perspective, a Kenyan lawyer pointed out that conflict situations increase women’s vulnerability to legal discrimination and gender-based violence. However, she emphasized that political training programs and feminist diplomacy initiatives have helped women enhance their advocacy and political participation skills at both local and regional levels.

These accounts collectively demonstrate that, despite the immense risks, conflicts have also highlighted women’s capacity for adaptation, leadership, and innovation. This serves as an important lesson for Sudan and other East African countries in designing sustainable empowerment programs that address the aftermath of conflict and promote women’s roles in peacebuilding.

The Diaspora and Feminist Diplomacy: Capacity Building and Knowledge Exchange

Within the diaspora, women have become influential social and political actors, transferring their local experiences to regional and international platforms while forging strong alliances to advance women’s rights. This form of feminist diplomacy expands the reach and impact of the feminist struggle, from raising awareness to political advocacy and legal reform efforts.

The Kenyan activist, who was raised with feminist awareness from childhood and studied law at Strathmore University, explained how her involvement in founding the Law and Politics Club in high school, along with her academic experiences, helped her develop skills in advocacy and feminist diplomacy. She added that joint workshops with Sudanese women enabled valuable exchanges of experience regarding women’s political participation in leadership positions, opening new horizons for regional influence.

Meanwhile, the Sudanese activist spoke about her practical experience with national organizations and local associations, such as the Child Care Association in Kosti, where she worked alongside Faiza Mansour, Salwa Al-Tayeb, and Mazahir Ibrahim to finance income-generating projects and promote feminist awareness. They emphasized that women’s economic and social empowerment facilitates their political participation and strengthens their influence within the diaspora.

The Ugandan activist, for her part, highlighted how women in her country, despite enduring the consequences of conflict and displacement, established economic empowerment and political advocacy programs, leveraging diaspora networks to exert pressure on policymakers and push for legal reforms, such as promoting political participation and combating gender-based violence.

These testimonies illustrate that feminist diplomacy within the diaspora is not merely a geographic presence, but a strategic tool for capacity building, knowledge exchange, and expanding women’s influence. From this perspective, several insights and solutions can be drawn for Sudan:

- Strengthening cross-border feminist networks to foster experience-sharing and mutual learning among women in Sudan and across East Africa.

- Linking economic support with political and legal empowerment, through funding small projects and training initiatives to increase women’s ability to participate in decision-making.

- Enhancing education and leadership training for women both at home and in the diaspora, to develop advocacy, management, and policy-making skills.

- Building digital and regional spaces for political influence, allowing women to engage in civic and political dialogue even under local restrictions.

- In this way, the diaspora becomes a vital space for feminist activism, enabling Sudan to benefit from regional experiences and strengthen its own capacity in building a feminist civil society.

Shared Challenges

Despite the political and social diversity of East African countries, women face similar structural challenges that hinder their access to justice and meaningful participation. The most significant of these challenges include weak implementation of equality-supportive legislation, the persistence of cultural norms that privilege men and reinforce traditional gender roles, and the continued threat of gender-based violence, which excludes women from politics through intimidation and social stigma.

Added to this are the lack of political will to enforce reforms and the scarcity of economic resources, which makes it difficult for women to compete electorally or establish strong sustainable organizations. Although the intensity of these obstacles varies by country, they collectively reveal an entrenched system of exclusion, making feminist struggles in the region inherently interconnected and interdependent.

Prospects and Solutions

In response to these challenges, women have developed multiple resistance strategies — from grassroots initiatives mobilizing local communities to feminist diplomacy in the diaspora, which amplifies women’s voices on international platforms. Youth networks and digital platforms have also created alternative spaces for advocacy and pressure, enabling women to bypass traditional constraints on organizing.

At the political level, some feminist movements have succeeded in pushing through limited legal reforms, while the broader hope remains in strengthening cross-border solidarity and building regional alliances. The sustainability of these efforts requires recognizing women as central actors in peace and democratization processes, not merely as beneficiaries of policies.

Thus, the East African feminist experience opens new horizons for Sudan to engage with and contribute to, through its own unique experiences in conflict resistance and civil society building.

Conclusion

Reading the East African feminist movement through a Sudanese lens reveals deep intersections among the experiences of women in Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, and Eritrea. Political violence, weak legal protection, and social exclusion weave a shared thread of struggle. Yet, women’s resilience and their ability to innovate, from grassroots activism to transnational alliances, sustain hope for a more just and equitable future.

For Sudan, engaging with these regional experiences is not only about learning lessons but also about contributing to an emerging regional model that highlights women’s roles as key agents in conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

The uniqueness of Sudan’s feminist discourse lies in its ability to merge three dimensions: the popular revolutionary spirit (Kandakat), the civil-legal struggle (such as the abolition of the Public Order Law), and the transnational activism of the diaspora. This fusion gives the Sudanese experience its strength and momentum, but also raises questions about how to translate this energy into a sustainable project for social and political transformation.

Comparative Reflections: The East African Feminist Movement through the Sudanese Context

Sources: This table was prepared based on reliable reports, publications and studies on women’s rights in Sudan, Eritrea, Uganda and Kenya (2017–2024)

For a deeper dive into how militarization shapes women’s lives across Sudan, South Sudan, and Eritrea, read our Gendered Frontlines report here.