An image illustrating the cultural diversity of Sudanese uniting against COVID by taking precautions and the vaccine. Source: UNICEF Sudan

It is said that taking a DNA test can be one of the most exhilarating experiences in one's life, as you get to find out about your ancestors and the different parts of the world you come from. From a health perspective, there are many myths with regards to the "genetic lottery" and how in the vast pool of genetics some are just blessed to have a lesser degree of exposure to certain diseases. To some, these tests may be stoking the fires of supremacy and dividing the world in the times it needs unity the most- like the middle of a global pandemic.

As humans, we are susceptible to getting sick regardless of our skin color, geographical location, or even gender. While it is true that some diseases only affect a margin of people for hereditary reasons, that doesn't afford protection, since even so-called gendered diseases like breast cancer occasionally affect men, while prostate cancer which commonly affects men, can affect women in extremely rare cases.

Inherited or innate privilege: where does health segregation based on race come from?

Back in the days medicine was plagued with myths; it was said that some races handle pain better, don't get infected easily, or are simply genetically superior. It is only propaganda to showcase strength, just as kings were thought to be anointed by God. Some like to think of themselves as ideal humans. This inflated sense of importance caused harm to marginalized communities and up to date, some medical practitioners differentiate among those seeking services based on their background.

With time some diseases have been linked to certain parts of the world, causing a stigma and ridiculing developing communities- although some diseases did become endemic in regions, their spread has nothing to do with the skin color or ethnicity of its citizens.

Fighting COVID not each other: the birth of hate crimes during the pandemic

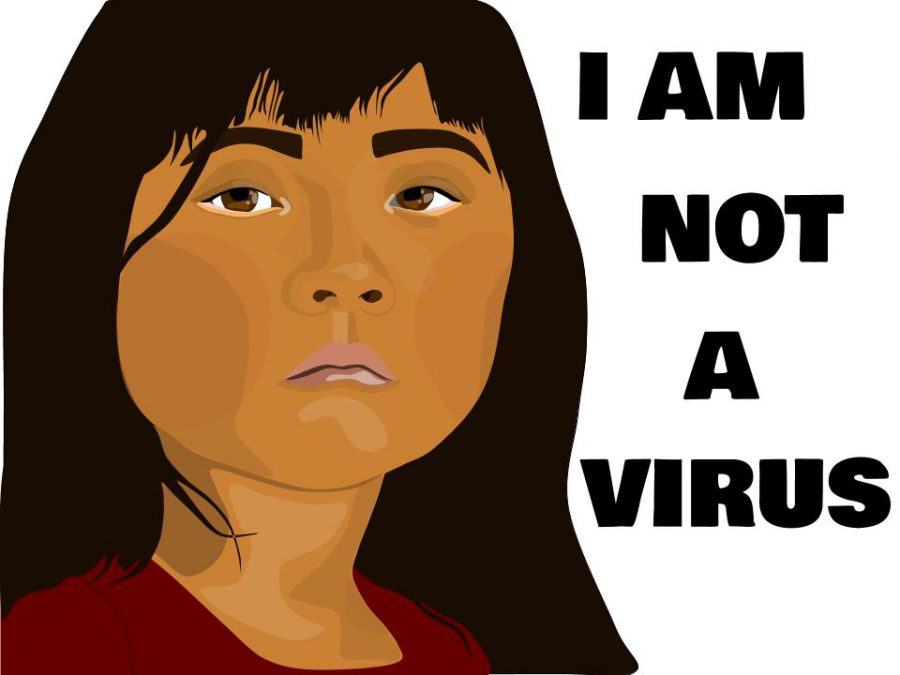

When COVID sprung out of Wuhan, China, many Asians across the world suffered hate crimes. They were racially profiled and targeted in public places due to some people believing they were the cause of COVID-19. Hashtags like #StopAsianHate set social media platforms ablaze pointing out the ludicrousness of pinning a disease to a specific genetic pool.

Another racial misconception that was spreading like wildfire during the first phase of the pandemic was that Africans are naturally resistant to COVID-19. The pandemic had only hit other parts of the world and was going to reach Africa. Since it took a while, people fell under the assumption that it would not affect certain ethnicities, but this was naturally debunked as the virus took over, not just the continent, but the entire hemisphere.

In Sudan, many rumors circulated over time around COVID-19, and it turns out that they have stages in their quantity and quality. The stages range from absolute disbelief, descending into resistance, panic that breeds contempt towards the truth resulting in many harmful misconceptions that refuse to go away, and finally accepting the truth about the virus.

This became evident as rumors started circulating that people in the Northern state refused to get vaccinated, but according to the Ministry of Health reports, "so far 187,000 people have been

vaccinated against COVID-19 in the Northern State and the number of the fully vaccinated individuals is 209,814 while the totally immunized are 120,945".

Another interesting angle rumors took is that the vaccine is distributed unfairly and some states get the vaccine after its functionality ran its course. This one can be easily countered when witnessing the vaccination campaigns that are being launched by the ministry of health in all 18 states simultaneously.

On a regional level, some African leaders came out to condemn the "hoarding of vaccines" by developed nations leaving poorer countries trying to wrench their share out as much as possible.

Many countries bought a staggering amount of vaccines far exceeding their need, making many see this as a racial undertone.

Yet the discrimination didn't stop at the vaccine stage, but continued even as the rollout reached full immunization status. Many Africans were denied visas and access to different parts of the world while their counterparts didn't receive the same treatment, all because they were vaccinated in African countries.

A man receiving vaccination at a health facility in Sudan. Source: USAID Sudan

Monkeypox: the sequel to COVID19?

As Monkeypox emerged in the world arena as a candidate to join the list of global pandemics, many news outlets used images of Africans when reporting about the virus. Sudanese journalist and analyst Hassan Barkia talked about the stigma surrounding some diseases and how the media widely circulates images of black people without conducting thorough research, especially for a disease like Monkeypox which is not widely known.

Berkia reveals that associating Monkeypox with Africans is reminiscent of people associating COVID-19 with Chinese people, because of where these viruses were first detected. In addition, a statement was released addressing this as the Foreign Press Association Africa clarified that “No race or skin complexion should be the face of this disease”.

Berkia notes that currently circulating images in the media depicting black-skinned people with lesions, may stigmatize Africans and thus associate the disease with a certain ethnicity or race. He adds that stigma is especially worse for individuals infected by a disease that develops visible symptoms, such as skin lesions for those infected with Monkeypox. This can have a strong negative impact on stigmatized groups, and people may feel lonely, isolated and even abandoned by their community".

Artwork that rejects the idea of making a race synonymous with a disease. Source: www.arhsharbinger.com/

A curtain call on the race segregation

More than two years into the pandemic, it is more apparent than ever that our differences should unite us and not divide us. Race is a part of our identity and should be celebrated, but not at the expense of others. Associating it with a virus or seeking protection not by precaution but by depending on genes is a harmful practice that will only prolong our fight against COVID19 and other emerging pandemics.