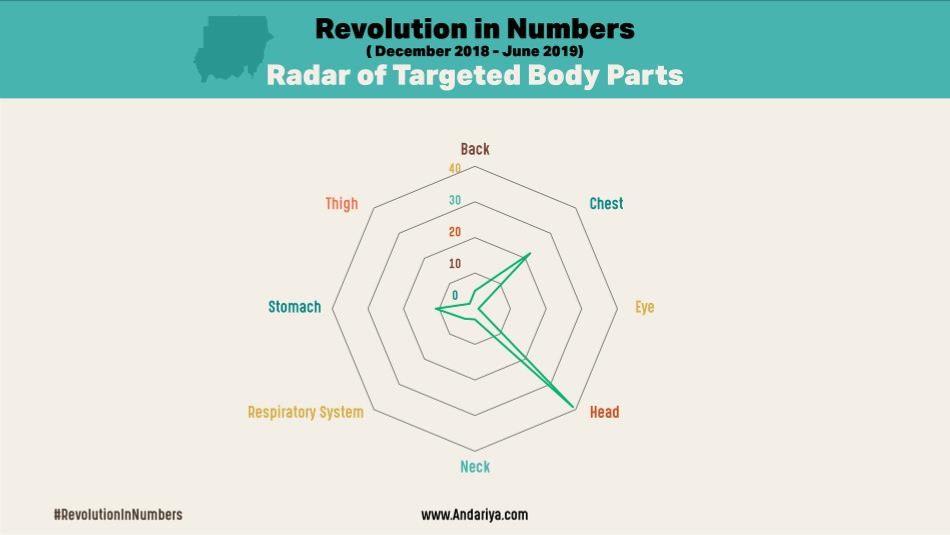

The rapid change in events since the start of the December 2018 revolution has been overwhelming and exhausting for us —as Sudanese people. From having three different presidents in one week in the beginning of April, to the death tolls increasing on an hourly basis on June 3, when the sit-in at the Military Headquarters was violently dispersed.

Many efforts have been done to keep sheets that carried the names of those who were – and still may be – lost or arrested, but it only gets more overwhelming, as it constantly needs to be updated because more names keep coming in.

The names become numbers – many of them. Yet, keeping them trapped in tables and excel sheets takes away much of what they represent and the sacrifices they made in the road towards freedom, peace and justice.

However, one way to preserve the importance of these numbers and data and what they stand for to life is transforming them into a different format with the help of a combination of methods such as coding and storytelling.

Writing and Coding

Creative writing and coding – what could they possibly share? Well, for one they’re both written in a language: English, Arabic, and Python – maybe, Java, anyone? But deep down, the two areas have one vital feature in common: working with data – and they both use data through different dimensions. Opinions, facts, and transcribed interviews are all examples of data required needed for an article. On the other hand, coding or and programming are also used for processing data, saving it in different structures, and presenting it to the end-user in the required format. When you combine these elements together, you get data journalism.

Isaac Asimov, known for his work on science fiction writing, has once put it this way: “But what if the same earth-shaking idea occurred to two men, simultaneously and independently? Perhaps, the common factors involved would be illuminating.” To Asimov, one way creative ideas are generated is when people of different backgrounds are able to make connections and spot intersections, in a way that may not have been observed before.

Now let’s try having a creative writer and a web developer (preferably data scientist/analyst) in one room, and see how the two can work together and what they come up with. In many places, like The Guardian, BBC, Chicago Tribune and other newsrooms, the intention is to move beyond the conventional reporting of specific events. Instead, they strive to create exciting cross-connections by having web developers work closely with writers and editors, thus, the field of Data Journalism was created (or the less cool name: Computer Assisted Reporting).

Why is Data Journalism Important?

Interdisciplinary storytelling is the way forward. As the borders and gaps between fields are welding with time and progress, the ability to develop tools that can help us hack problems will improve, since the complexity of changing landscapes is increasing as well.

With the availability of open and public tools for data exploration, joined with the creativity of writers in providing context and giving meaning to data, producing more detailed in-depth investigative pieces can be an augmentation of the traditional approaches. And this is exactly what we need to turn significant numbers into an engaging and insightful story.

Impact and Data Graphics for Advocacy

The most important element here is data. And the motivation is always impact. This doesn’t only apply to data analysts and coders, but your average readers are also becoming interested in the raw facts behind stories more than ever.

For instance, data can be used in identifying shortage of services in specific areas through the use of mapping and impact can take place in holding corrupted officials accountable.

People always want to know more: the number of doctors in Sudan in relation to the number of hospitals across different states; the difference in death tolls influenced by key political events; how frequently Hemeidti uses certain words in his televised speeches; tracking the fluctuation of dollar/SDG exchange rate over a periodic interval of time – starting from December 2018 until today.

But that’s not all, others may be interested in the effect of flawed urban development policies and practices, or pinpointing areas where poor practices are contributing to structural problems. For example, data can help in analyzing water quality in Khartoum’s outskirts, reporting on it and developing initiatives based on the findings.

The keyword to make an impact is always data. Nevertheless, data without context is meaningless. So we have a second keyword: writing.

Picture this: a team consisting of a writer and web-developer have this new job: investigating and finding stories. Both are using different tools, but they share the goal of working on data-powered stories.

“Data alone won’t get you standing ovation; stories will. Stories inform, illuminate, and inspire. Tell more of them.” – Carmine Gallo – Harvard Business Review.

Open Data As a Tool for Empowerment

Thanks to the internet, many tools are free and open-sourced. There are many creative writers out there with varying levels of editorial backgrounds. There is, however, one challenge that can stand in the way: and ironically, it’s the data itself!

Access to data can be restricted as governments may not have organized access to information laws. In particular situations, the data does not exist to begin with. And if it does, you are not always guaranteed trustworthy databases released by government entities.

Since data is a tool for empowerment, and empowerment isn’t always easy, data has always been difficult to get. Imagine what free and available information on anything Sudan-related, fluency with data, and a sharp critical sense of a writer would look like and what it can bring to the table. Putting this concept of freely published data into practice is not only helpful, but downright necessary.

If we look at the Sudan context, smaller towns usually fail to attract attention of Sudanese media outlets. However, there is always an opportunity for the residents to be equipped with capacity-building and training on data literacy so that they become their own data journalists and have ownership of the reports on the obstacles they are facing. That way, they gain the skill of data collection, but also, the advantage of credibility and knowledge of what and how they want to report are now in place.

Moreover, when the data is hard to attain, collective efforts of data crowdsourcing can come into play. This practice is not only an efficient alternative, but it would help researchers and Sudanese activists with the stories and fact-based reports they are working on; especially now in times where reporting and data are becoming a time-sensitive priority on a national and international level.

Conclusion

Data is a scary word. It can be – and often is – boring, confusing and sometimes exhausting to work with. But its role in empowerment and getting closer to the truth cannot be denied. As data journalism evolves, the future will involve more web developers and data scientists working on newsrooms, and more writers and journalists with superb data skills.

When the two cliques begin working side by side, combined with serious capacity building and open accessibility to data, it will be a profound benefit to our country – setting us on the path towards more knowledge accessibility, credibility and progress.