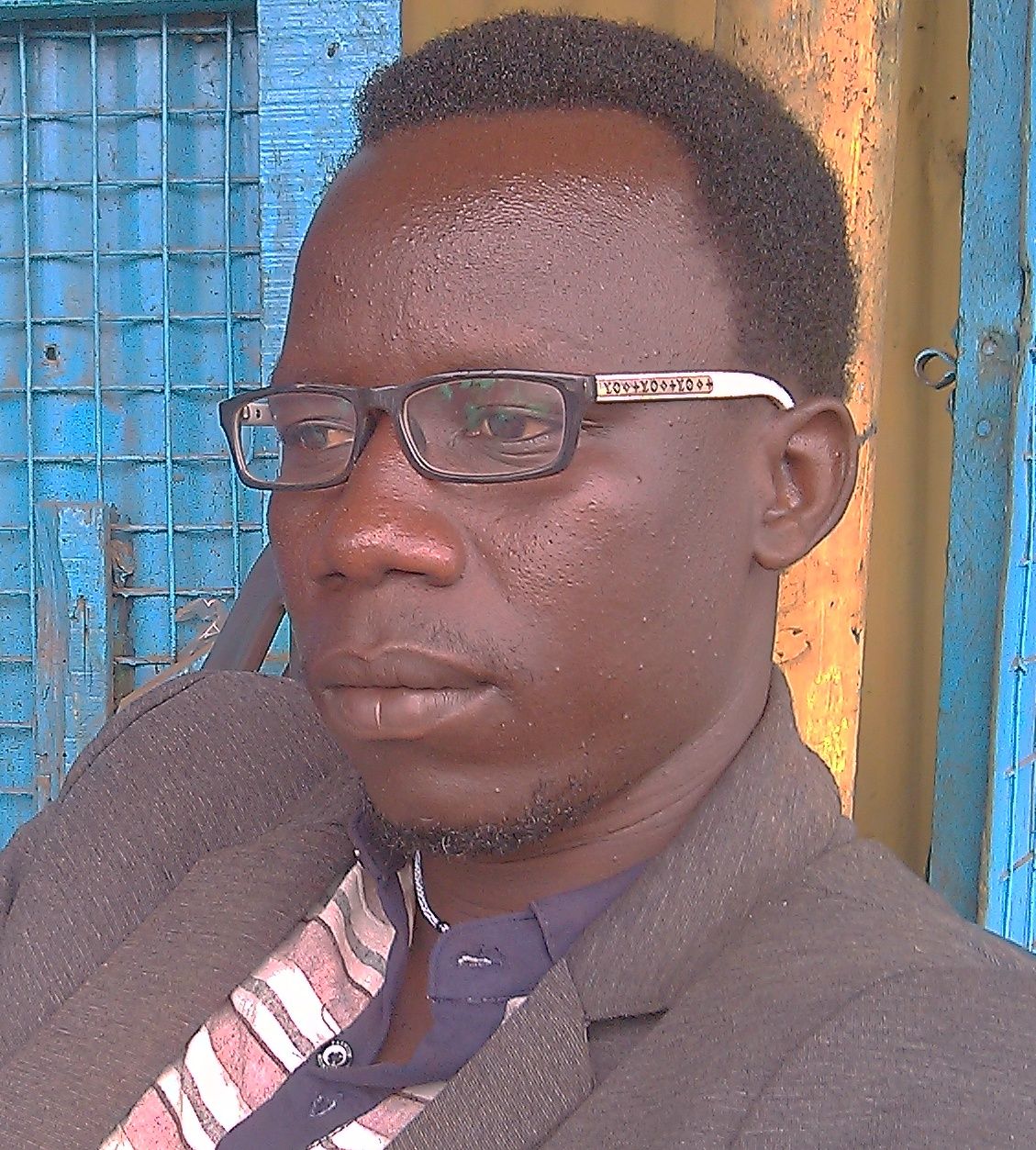

Viviana Niashan was born in 1965 in Malakal in the Upper Nile State, to a family of famous artists and musicians. From an early age she began to sing in her mother tongue (Chlo) and currently sings in four local languages. Viviana entered the music scene in 1992 and released her first album in 2000 and continues to sing until now. The disrupted conditions and suffering in South Sudan breaks her heart and stunts her art and ability to use her talent. She still has passion for local languages and traditional art and eagerly awaits peace so she can sing for joy to the people of South Sudan. In this interview, we learn more about the folk art icon Viviana Niashan.

Andariya: Who is the artist Niashan?

Niashan is my nickname, but my real name is Viviana Niashan James Shuai. I’m from a well-known area in the north of Malakal, a town called Loul, and I am the mother of four children.

Andariya: Where did you grow up?

I was born in Malakal in the neighborhood of Modariya, and after I was born the family moved to the neighborhood of Denkershovo, then to Jalabba neighborhood and, finally, after I got married I settled in Osossa neighborhood. I received primary education in Loul secondary area of Cdok and then continued on to the Teachers Institute in Malakal.

Andariya: When did you start singing?

Art runs in the family, my uncle the older brother of my father is a famous artist in our region. He composes and sings songs of praise, eulogy and dance. Since childhood he discovered me and said that I would be a great artist in the future, back then I used to sing in the church and compose girls’ songs during weddings.

When I first started I wrote my own songs but sometimes sang the songs of others without imitating them. As for performing on stages, I liked renditions of traditional songs from our tribe using the traditional instruments that would make the people dance as I sang.

I came out of the tribal public eye to the mainstream after finding guidance from reputable artists before the separation of the country, such as Abdul Qader Salim and Ahmed Alrayah. They used to mentor me and insist that I should make my talent public beyond tribal audiences. I traveled with them to represent Sudan abroad in Switzerland and Syria before the current war in Syria, when the Sudanese community abroad used to invite us for concerts.

Andariya: Do you currently sing in your local language only?

I love to sing in my l local native language (Chlo) to send a message to a specific category in the community in which I live. However, I currently sing in other languages, but I am not as good at them and sometimes the message is not clear.

Those who guided me kept saying that I am confining myself in the Chlo language and encouraged me to imitate songs in other languages; even if I couldn’t master the language itself. I experimented with the idea and sang the late songs of Madisha Mukubi in the Moro language. Currently Moro songs have a strong impact in art and society in South Sudan.

I also sing in the languages of the Dinka, Nuer, Bari and a little bit of Jorashwl. This effort is to satisfy my audience, but despite all this effort, I am more comfortable when I sing in my local Chlo.

Andariya: who are the most prominent Sudanese artists you worked with?

The list is long; I was a member of the Sudanese Artists’ Union so I know many artists. But there are many I remember from the past to the present and I cannot forget their impact on my career, even after the separation. I worked with the artist Abul Karim AlKabli on traditional and heritage related works. I was also on TV with the artists Ahmed Alrayah and Wad Al Amin.

Andariya: have you ever sung any of these artists’ songs?

They often try to make me imitate their songs in Arabic. There was a Sudanese poet who wrote me a song in Arabic, but I did not sing the song, because I do not know Arabic very well. I justified it by telling him that knowing the language and singing in it are two different things.

Andariya: But you have songs in Arabic?

I do, but I was always shy of my Arabic and eager for criticism because there are many South Sudanese who are fluent in Arabic. At the flag-raising event after independence I composed three songs in Arabic, but returned to my mother tongue again because I’m more influenced by my language. Whenever I think of Arabic songs the idea that I am not fluent in the language pops in my head, but I enjoy many Arabic songs especially the song “Ard Al Khair” by the well-known Sudanese artist, the late Ibrahim AlKashfi.

Andariya: When was your first appearance on stage?

I entered the art scene in 1992 in Khartoum during the mass waves of displacement. The experience was good for me as an artist because of the interest in our culture, especially in exile; people care about connecting to their heritage. The first appearance of South Sudanese singers was due to the efforts of South Sudanese students in universities and colleges who invited us to perform on their stages in Khartoum during official ceremonies; such as graduations or cultural seminars. This encouraged people to show the Southern art in public in Khartoum and there was my first appearance at the a university theater; but I was already famous in Malakal before displacement to Khartoum.

Andariya: When did you release your first album?

The first official album work was in 2000 and titled “Wad Aqunah.” The experience was unique because I was the first solo Southern artist to release an album and sell and distribute it in South Sudan and abroad. Before me an Equatoria region band released a formal album & distributed it locally and abroad. I may not have had a financial benefit from it, but the experience has opened the door to southern artists to release albums, and I tried to help them on how to do it.

Andariya: Tell us about the album name?

The album was named after a city by the same name, Wad Aqunh, located north of Upper Nile State in the Mang County. I sang about the beauty of the region and the community and the wealth, and how all the tribes of southern Sudan had moved to this city when they returned from the North. I visited the city in 1999 and I saw all the people sleeping inside the open fence and no one asks the other, and not a single voice of a weapon, and the masked would sing in the street for freedom. I remember I went to the Nile to buy fish and it was very cheap. The people were very simple and content. The same night I composed the song and named it after the city.

Andariya: Did you receive any help while advancing your career?

I did not find help financially, but moral support was offered by my audience who liked my songs. In Southern Sudan and typically those who like music are poor just like us the artists.

Andariya: you sang for peace and separation and it was achieved, how do you see the South Sudan now?

It is a nice theory, in my opinion, but I have a song that did not come true until now, I sang it before the signing of the Peace Agreement, in the days of the civil war in a united Sudan. The song was a message to all parties of the war on the grounds to stop the war to spare lives, especially women, to settle freely and never hear the sound of weapons so they can live in peace. I sang the song in 1992 in a cultural program in Khartoum, and when I sang the song on stage for the displaced southerners in Khartoum, everybody –myself included-cried. The content of the song calls on the parties to stop the war, and leave everyone to move freely (in the sea the fisherman and the field the farmer) without distinction or color. When I sang that song everyone who lost someone dear shed a tear. I thought that the song ended with the force of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, but when the war came back again the song once again became relevant. I hope that peace and stability is achieved.

Andariya: What is your outlook for modern music in South Sudan?

It represents human culture and it is not a constant, with the development and globalization we must add new things to the culture, songs and music while preserving the African rhythm. Personally, amid my Southerners family, I love to sing with “tmbur” and thought about issuing a new album before the war in 2013. I wrote a song for the kings of the Chlo tribe to the rhythm of traditional “tmbur” and it would have served as a heritage preservation effort.

Andariya: What do songs mean to the tribe?

The songs of the Chlo tribe signify joy and peace, and are divided into songs of joy and sadness.

Andariya: Did you sing about love?

(Laughter) How can an artist not sing about love? I’m an artist and each artist should sing about love, even in the church we sang about love.

Andariya: Many of the music listeners are now into pop songs, what do you think?

Indeed true, and this is one of the threats to art in South Sudan and the reason is the lack of a committee to regulate the standards for literary works and poetry. The blame cannot be on the artists because of the way they sing, perhaps they want to introduce a foreign culture they are familiar with, it becomes our task to guide them towards the traditional culture of South Sudan, which requires the presence of a regulatory body.

Andariya: What is the impact of war on the artist?

I personally have been affected by the war; the only thing left is to become a martyr with the martyrs. I lost family members and children that I used to teach. I thought about retiring, because there is no meaning for singing since artists sing out of joy, and the war has exhausted my strength and my talent. So far, even after signing the peace agreement, there is no peace.

Andariya: Do you have a new project for your fans?

The news is I would like to announce my retirement from singing. I’m one with the people and just like them I’ve grown hungry, so how can I sing in such circumstances? And for whom and how these days?

Andariya: A final word?

I want to thank the people of South Sudan for their patience, and I advise them not to give up like me, they have to continue and there is time for everything.