South Sudanese cinema is in its nascent years, but the depth and scope of films produced in the last few years is promising. We’ve witnessed three editions of the Juba Film Festival showcasing diverse films produced by South Sudanese filmmakers ranging in topic from politics to culture and social norms. Independent award winning productions also saw the light in the last three years, such as Zawaga Gali and DEFY the Film.

In celebration of Women’s Day- which we’ve turned into a Women in Cinema week- we’re thrilled to present Akuol De Mabior, a young up and coming filmmaker tackling incremental topics such as colorism and intergenerational taboos. Akuol directed “Tomato Soup” and “Fall into the Sky” while she was studying at the University of Cape Town. The two short films are enticing in their cinematography and gripping in their genres; Tomato Soup is cringingly hilarious while Fall into the Sky leaves you mouth agape and heart pounding from its intensity.

“Fall into the Sky” is a 9 minute experimental documentary exploring colorism, Afrophobia and belonging from the perspectives of black women and women of color in South Africa, through the use of performance and song. The film was directed by Akuol De Mabior and Chriten Torres with Kamvelihle Stemala as the cinematographer. The pieces featured in the film are by Julie Nxadi, Babalwa Tom, Philippa Kabali-Kagwa & Afeefa Omar. “Tomato Soup” is a three minute dramedy that explores themes of body shaming and intergenerational tension between women in a South African context. The films were screened at festivals and venues such as Durban International Film Festival, Reel Sisters of the Diaspora Film Festival, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa and the African Consciousness Institute.

While her forage into filmmaking was not direct, her journey was instrumental in her ability to use filmmaking for storytelling. In this interview we delve deeper into the mind and vision of Akuol De Mabior.

Andariya: How did you get your start in filmmaking?

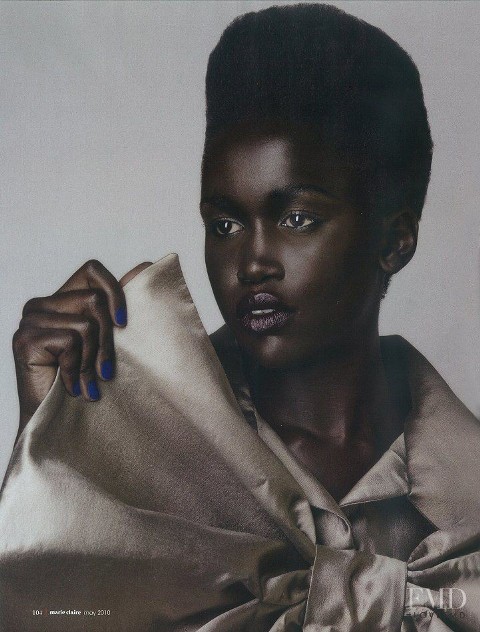

Akuol De Mabior: I used to model for five years, I lived in New York, Paris and London and it went well sometimes, but didn’t go well a lot of the time. I decided at the end of 2014 that it wasn’t going to be sustainable, or let’s say I had the courage to realize that. It felt like walking with your back facing a cliff and the ground is falling behind you, but it looks great ahead of you, yet you feel something is wrong. I think of it in such strong visuals because it took a dream, a very visual dream, for me to get the courage to realize that this isn’t working. It’s really seductive, it holds you. I’ve seen people who remain in that industry when it was completely not viable and it ravished them, but they still stayed because there is the promise that the next thing will be IT. It’s not just modeling, it is the entertainment and sports industries as well; people stay longer than they can. It’s difficult to talk about these industries, because people revere and revile them at the same time.

I saw that this isn’t going to work, but I was anxious because I didn’t have any skills and I was given – even until now – a sense that modeling is the only thing I should be doing. People look at me - and at people who look like me - and say “you should be a model”. I decided to go back to university and while I was there people still asked me “why are you here”. So even then I felt that people gave me limited options of things I could possibly be. We can be many things and that’s to do with aspirations. I went back to university because I felt that I had no skills.

Source: Marie Claire

Source: Marie Claire

Andariya: Why Film production?

Akuol De Mabior: I decided on film production because my whole family has an artistic streak. My brother is a great painter and my sister studied fashion design. I always felt like I was neglecting that aspect of myself, but always knew one day I’ll go back and nurture it- but then I didn’t have the passion. I remember I was speaking to someone about an idea I had, and they suggested that I should make a film. It was such a huge moment, because I felt like this would be an extremely demanding challenge that requires so much. When I was modeling it was demanding but one dimensional, so I didn’t approach it creatively. For filmmaking I knew I needed to hone many skills and do it collaboratively and each project would be a big mountain to climb and this made me enthusiastic to achieve something.

Then it was a matter of how does one make a film. I contacted my old university (University of Cape Town) from where I had failed out badly five years before. I didn’t even say bye, I just disappeared. They let me come back on a lot of conditions to study film and media production. I made some films through that and all of them went to at least one festival.

At this stage I’m trying to figure out how to get my films seen. In the past years I’ve focused so much on film creation that I didn’t focus much on audiences. Right now I’m starting a media company that is focused on representation, aspirations, cultivating a renewed African imagination and using digital and social media.

Andariya: How has your education impacted your journey?

Akuol De Mabior: I’m still new to filmmaking; everything I’ve made thus far has been done while I was studying at University. Right from the start there was a debate around whether I need to go to school for it or not, but I’m a good student whether at university or in life. I failed out so badly before, but with a renewed sense of focus, I did really well and thrived. For some people going to school for filmmaking is unnecessary, but I needed that structure for myself. I learned well in that environment and I didn’t know I was going to because of how badly I did in the beginning. I’m attracted to filmmaking because of how complex and collaborative it is; you need a group of people who really believe in whatever the project is, to come together and put their minds together. And I liked it because it’s art; we were taught about filmmaking as storytelling.

I had four majors: I did media studies, gender studies, film theory and I specialized in film and media production. It was very theory heavy, but again it is a university course so it’s a lot of theory, but I enjoyed this element too.

Source: Fall into the sky press kit

Source: Fall into the sky press kit

Andariya: How did gender studies influence your work?

Akuol De Mabior: The perspectives of women are so important to me, because they’re the ones that are omitted and trivialized I find them important, and because I identify as a woman. I read Alice Walker’s chapter on colorism in her book “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” which she wrote in the 80s. She was the one who pointed me to the term. It sounded like an appendage to racism or a euphemism to racism, but it’s a whole other thing. When you tell people it’s the preference of light skinned people to dark skinned and the rejection of dark skin then it registers with them. So we had this conversation in depth because in South Africa there is a perception that they are all light skinned. Gender studies allowed me to delve into such concepts and really understand them. I finished the major and even taught it last year for first and second year students. I think it’s so important because there is omission and trivialization of gender issues. Some would mask comments under humor and you’re supposed to take it, and if you don’t then you’re a bad person. I appreciate a good sense of humor, but humor can be used to mask hateful and hurtful sentiments.

Andariya: How did you develop a Pan-African filmmaking scope?

Akuol De Mabior: The last film we made was “Fall into the Sky” and it focuses on colorism, Afrophobia and xenophobia from the perspective of black women, colored women and women of color in South Africa. Colorism and Afrophobia are things that I’m familiar with; they are things that I cannot not think about, just by being and traveling to many places in the world. It was always brought to my attention that I’m an African, and often done in ways that were hostile and negative and it’s usually not white people. That is colorism – it’s how we do that to each other as black people and colored people and people of color. Just from having that drawn to my attention all the time, I guess I have given it a lot of thought. I think we underestimate and trivialize how important symbolism and representation are. We just want to be affirmed and if we don’t experience the full spectrum of our humanity, which means facing pain and discomfort, then we still suffer.

So there you are sending out your Monday Affirmation Mantras to feel good, but you’re not willing or able to experience the fullness of your humanity. What we want to challenge is that such approaches only allow for one thing, which isn’t necessarily bad, but it’s not complex. What we want to draw attention to in our films is the complexity of who we are and Pan-Africanism would contribute to that; us being able to regard ourselves in our complexity without tearing ourselves apart. There is a sense that it is impossible; we have been so compartmentalized to simplify things to a “we are all Africans and it’s all fine”, but we are different, yet we can live together and regard each other in our fullness. That oversimplification will always end up tearing things apart and it means that aspects of yourself go quiet and if you silence aspects of yourself, they don’t go away, they fester and return.

Source: Tomato Soup press kit

Source: Tomato Soup press kit

Andariya: What’s your filmmaking process?

Akuol De Mabior: I am continually developing processes. Much of it has to do with the people that I’m working with. All the films I’ve made have been as a university student, and I had the great fortune of becoming part of a team of brilliant women of color. We shared experiences in our white-dominated class of feeling our perspectives were undervalued, and as the class representative, I spoke up, and we did something about it. We realized that we would continue to experience this if we pursued careers, because, even in South Africa, the film industry has representational issues. So, we organized and found ways to make work that mattered to us.

As a director, I try to be as organized as possible. You have to have your eye on so many moving parts and things go wrong all the time. I’ve realized that you can almost never be too prepared to go into production and post-production and there’s almost never enough time or money. I love the process, including the tedium and intricacies, the fact that it’s so exacting and demands that you submit all of yourself to even make something half decent.

Andariya: What’s next for you?

Akuol De Mabior: I’m currently working on a music video with one of the emPawa 100 artists. I’m also developing two web series: one with the working title Wife Material about how hypocrisy festers in the space between tradition and modernity. The other with the working title Byte This, a cooking show that explores internet food trends. I’m also working on getting my business up and running. It’s a media company called A Place Outside (APO). I’d love to make content that all kinds of African women can watch and relate to. Content that we can love and hate, and dream about, that can confirm and disturb our opinions. My mission is to contribute towards the cultivation of a renewed African imagination and to bring our aspirations home.