Once upon a time, around 1930, a boy named Abdel Aziz Dawoud was born in a smallish town north of Sudan. Orphaned as a child, he went to work at an early age while attending the local khalwa (Quranic school) where he stood out among his peers for his sweet voice; a voice which would take him places, according to his teacher. Of course the teacher meant places in Quran recitation, but instead he came upon the boy singing his heart out at his friend’s circumcision party and threw him out of the khalwa in disgust. Later, Abu Dawoud – as he was later known – would move to Khartoum and become one of the best known and most loved singers of his time and the times to come. His wide smile and sense of humor made the memory of him a pleasant one, long after his life was cut short at the age of 57 in 1984.

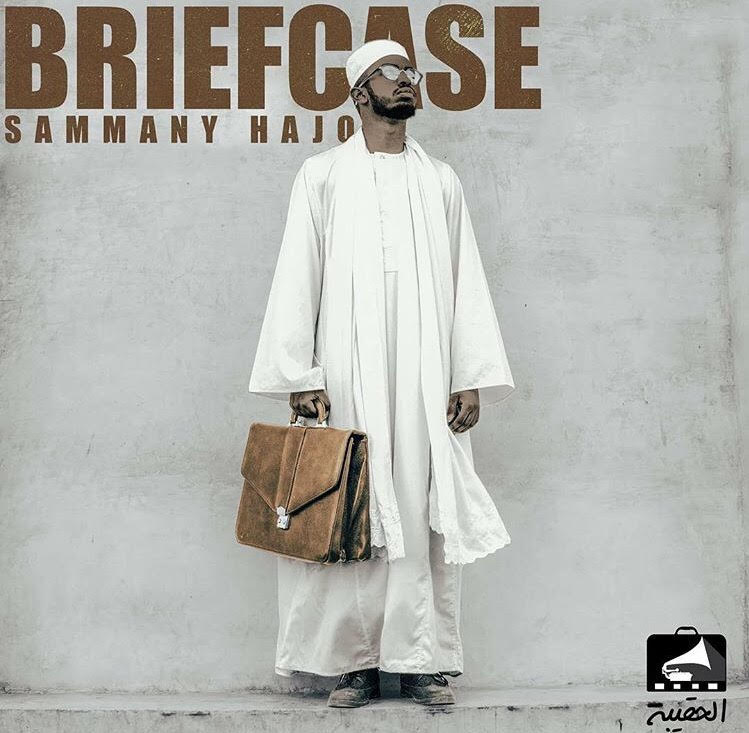

Thirteen years after Abu Dawood died, another boy by the name of Sammany Hajo was born, not in a smallish town north of Sudan, but in a city in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The boy grew up moving around the Gulf, listening to Abu Dawoud – and others – which his parents played around the house, much like almost all kids of his generation born in the diaspora to parents who missed home. This boy would come to view Abu Dawoud’s music – and the music of many others – in a different light, with a different potential. Until he was finally armed with his own sense of rhythm, some self-taught music skills and a collection of home-use music making software, he would begin to reintroduce Abu Dawoud’s beautiful voice and music to the world in a 21st century packaging that the man himself would have no doubt been proud of. The release of the album created a stir on social media, and two camps were born, dividing the fans from the critics. Although Sammany released a few tracks to give us a taste of his production-in-process, the diversity of the Briefcase EP was beyond everyone’s expectations, thus discussions ensued, involving the artist and exploring his reasons & philosophy.

Sammany: “To be honest it all started as a personal thing. I grew up listening to Sudanese songs and at the same time I loved hip hop, R&B, jazz and other genres. So when I started making music, the idea of mixing Sudanese music with other genres was always at the back of my mind. I just never thought I’d be capable of doing it. So I released “Min Zaman” and people loved it. It made people [want to] hear more and some of them were asking me about the original song.”

The original Briefcase (translated from the Arabic El Haqiba), is a large and somewhat ill-defined collection of Sudanese songs from the mid 20th century, combining strong words and songs by both Sudanese and non-Sudanese poets and musicians. The name comes from the briefcase that the radio presenter Ahmed Osman used to carry the records in and from which he selected the different tracks to play on his radio show back in the 1920s. Over time, these songs became the staple of Sudanese music, with every new genre introduction compared with and torn down against these ‘original’, ‘authentic’ songs.

The Haqiba songs have been made and remade a gazillion times each over the years, until the entire Sudanese music ‘industry’ has become nothing more than one beat-up Haqiba itself. The songs have party versions, bridal dance versions, somber, sophisticated versions and new covers for each occasion. Choirs sing them at schools and universities, and they play on the radio all day long. People are just about sick of them and at the unoriginality of the industry, although they still tend to be preferred to the new, mostly low quality new works of music. So yet another remake/remix isn’t exactly welcomed with open arms by everyone. Nonetheless, Sammany’s Soundcloud plays jumped from 2K plays a day to a whopping 35.9K in just 24 hours following the release of the tape. Anyone with any basic knowledge of Sudanese music knows that Sammany isn’t exactly doing anything drastically different. So what’s new here?

Sammany’s samples of the original songs in his music are the same relatively low quality recordings by the original singers, with his own reggae, hip hop and R&B fusions. However, the remixes are not extreme enough to ‘ruin’ the original songs: many die hard Haqiba fans have admitted to enjoying the remixes as they do ample justice to the originals. Indeed, when my husband sent me Abu Dawoud’s original song (after hearing Sammany’s remix of Yahlelom), I was pleasantly surprised that the original was just as nice as the remix – or the other way around, I guess. I admit I felt a tad more sophisticated, having listened to an original Haqiba song from beginning to end. The downside to this, of course, is that not all the recordings are clear, and with the strong overtones of the new music, the original words can get somewhat jumbled and lost.

However, for many of us, this music represents something much bigger. For an entire generation that grew up outside Sudan, missing a home we never knew except through our parents’ stories, memories, and most importantly, music, very few of us did not hear these songs played at some time or another. Personally, growing up between New Zealand and the Gulf and only coming to Sudan as an (informed) adult, my siblings and I grew up hearing these songs playing from the cassette player in the car and at home. I distinctly remembering hearing Wardi’s Arhal sung by my mother in the kitchen over a pot of something or another. This music represents the Sudan our parents lived in and loved; a Sudan of prosperity, justice, sweet clear nights, productive and peaceful days. The Sudan of open air cinemas and concerts, of high class education and free health care. Of course, that Sudan was far from perfect, but it was a much better version of the Sudan we know today. And the music Sammany produced seems to bridge the gap between that bright, shiny Sudan and the current dusty, tired, beat up reality we’re stuck in.

And so, Sammany’s Briefcase is both familiar and new, nostalgic and intriguing, and something that we can relate to both through memory and the current mixed-cultural taste that globalization has had the audacity to instill in us. For many people, this new music fusion is the first time they have been able to actually ‘listen’ to these songs and begin to appreciate them. For others, it’s a successful way to introduce Sudanese music to non-Sudanese audiences, since the beats are universal enough to be liked, yet the sampling is Sudanese enough to be local.

So what’s next?

Sammany: “I’m definitely planning on exploring other things. I actually [want to] take a little break from making beats and focus more on actual instruments and performances. It’s very restricting to only remix Sudanese songs. However, if I get the chance to collaborate with musicians and professional studios, I’d love to remake some Sudanese songs. A Briefcase 2.0 perhaps, minus the samples.”

Briefcase 2.0? Bring it on.