Literature was one of the most affected cultural pillars during the Inqaz regime rule, with rife censorship, bans and persecution of its actors.

Mr Ahmed AlFadul Ahmed was born in Wad Madani in AlGezira state in the 1950’s and resides there to date. He focused his passion on reading and writing children's books at an early age, however, The major turn of events in his life was when he joined an educational institution, known as Bakht Ar Rida. Prior to that, his attempts to join the school failed as a ministerial directive entailed that students enrolling in secondary school should not surpass the age of 17. He was a few months older when he joined to continue his educational journey, but he was unhappy with the situation at the time.

Outside of a stationary shop. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Outside of a stationary shop. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Bakht Ar Rida had one of the largest libraries in Sudan, second to the one in Khartoum University. It had a great impact on his literary direction and allowed his perceptions to expand after exposure to literary publications coming from Egypt, Lebanon and others countries. It provided him the tools necessary to gain knowledge around art, leading him to his artistic path.

During his final year at Bakht Ar Rida, before his graduation, he began writing. He wrote a story that was awarded 3rd place in a literary competition in the mid 60s. Despite the naivety of his story, he says, it was a clear indication of his innate talents and abilities, giving him an incentive to continue. He followed in the footsteps of great writers such as Nagib Mahfouz, who influenced his writing structure and development. Ahmed AlFadul also began to be more experimental with his writing and pursued publications.

As a result, his story ‘Searching for Another’ was published in a magazine in Omdurman called ‘Huna’ (Omdurman’s Radio and Television station’s printed publication), that focused on arts and culture. His writings henceforth flooded ‘Huna’ publications, and many other cultural and international publications such as AlDoha magazines and AlSharq AlAwsat. His literary work was also translated into English and published by the Sudanese Embassy in Washington.

Gezira Printing Press. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Gezira Printing Press. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

He also worked as a teacher, a collaborator, an editor and presenter at AlGezira State Radio and Television station. In his work as a teacher, he was able to visit different areas in Sudan, such as the South, the Center and the West of Sudan. His trips extended to the region as well. This gave him a chance to explore different societies, and fueled his writing, powering many literary trends in his works. His capabilities in the field of literary critique also led him to became one of the judges in Al Tayeb Salih’s Literary Prize, for three years.

He reflects on this experience fondly, stating “man cannot just create, creativity is sparked through reading and experience”.

Gezira Printing Press. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Gezira Printing Press. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

In the mid 70s, he joined AlGazira Literature and Arts Association (established in the early 70s in Wad Madani). This fastened his contact with intellectuals and writers who attended seminars, literary nights and festivals. The Association was interested in all forms of art, including writing, poetry and theater to mention a few. Those who joined became involved in the literary arena and their contributions were documented in cultural festivals, such as the First Cultural Creativity Festival in the Central region of Sudan in the early 80s. Works from research to scientific seminars to the renaissance of theater, were captured from all parts of the country to showcase in the festival. The festival deepened cultural understanding and stood as a pillar of culture. The Palace of Culture in the city of Wad Madani stands today because of this festival.

Censorship During the Inqaz Era

Mr. AlFadul continued writing and publishing in the magazines during an unprecedented era, where it was very difficult to assemble a collection of stories and poetry. The Publishing House at the University of Khartoum was the only governmental institution authorizing publications. Although commercial publications also played a role, they had no interest in creativity due to their limited resources and audience reach. On the other hand, writers at the time did not fully grasp the importance of printing books.

In Sudan, The Inqaz government intentionally set out to destroy any cultural project that saw light, censoring books and promising writers alike. This led to Sudan not contributing to publishing Sudanese books written by Sudanese writers, who opted to publish abroad where publishing was made easy for the diaspora. Thus, the works of Sudanese writers of a certain era can be seen in many Egyptian and Syrian publications. Governments do not produce culture, but they often shape it, and the Inqaz government intentionally and directly contributed to destroying and limiting arts and culture.

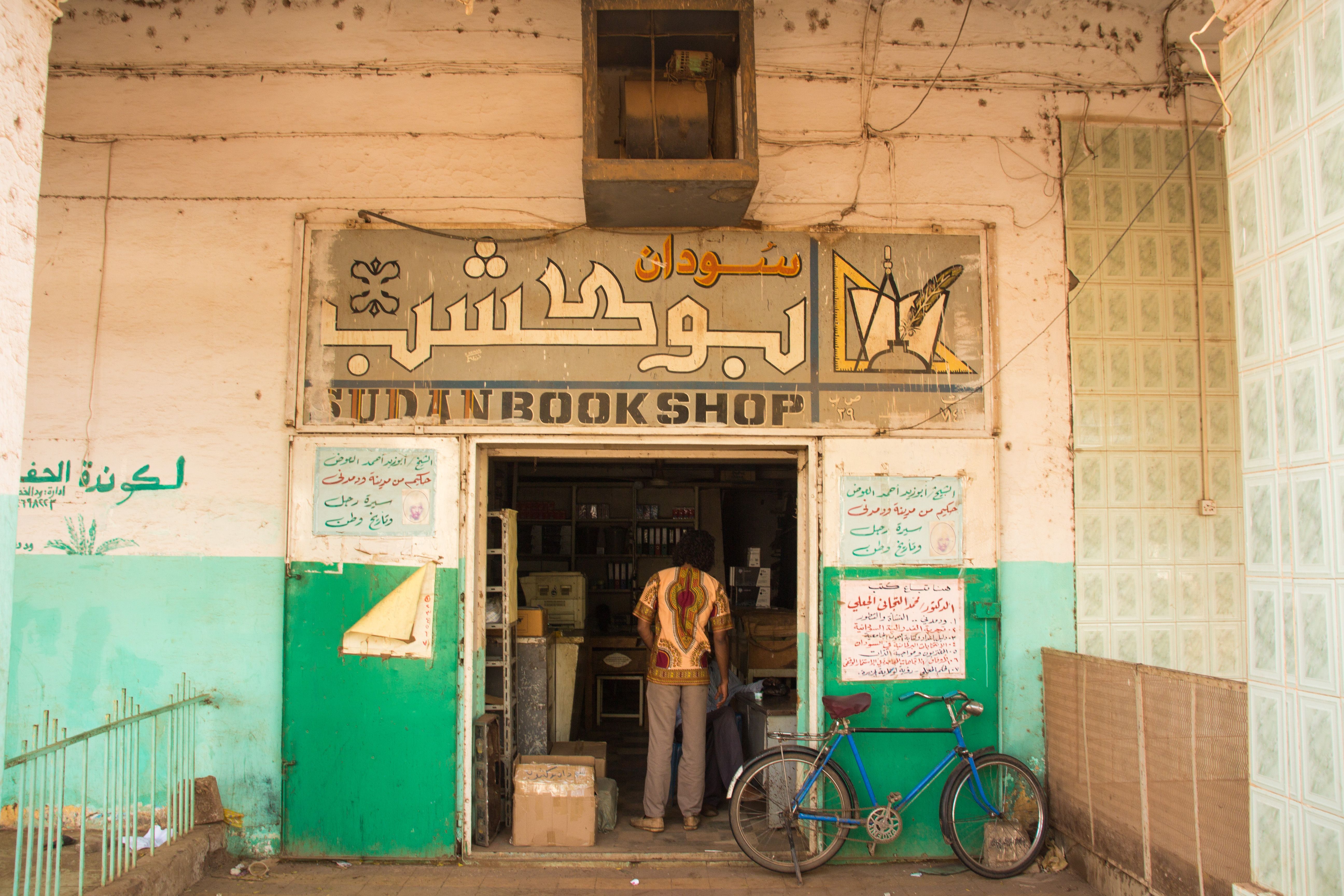

Sudan bookshop; many books by Sudanese writers are sold here. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Sudan bookshop; many books by Sudanese writers are sold here. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Sudan also implemented censorship of international cultural trends during the 30-year dictatorship. AlHilal magazine was one of the magazines expurgated from Sudan, obstructing the flow of culture into the country and limiting its local writers and intellectuals. Mr. Ahmed AlFadul says “readings during the era felt almost criminal, most readings were done in secret. Publications from other countries were smuggled in, and harassment towards intellectuals in AlGezira Association for Literature and Arts continued. The government would often cancel seminars with no apparent reason”.

There was no clear vision for the development of the literary sector in Sudan; writers had no help and publications were heavily monitored and censored. It was hard to find writers devoted to writing with the precarious environment they dealt with.

Mr. AlFadul has four publications, three of which are a compilation of stories and novels. His first publication was titled ‘A Transparent Man’, printed and published at Azza for Publishing and Distribution in Khartoum in 2003, as a gift from Mr. Ali AlMac. He says that the printed version was not revised, and it contained many errors, therefore it was not issued. The second was ‘AlAbwab Station’, published in 2001 at the Sudanese Studies Center that belonged to Dr. Haider Ibrahim. ‘Spaces of Dream and Exile’ was published in 2005 as an initiative by two friends, Mouayia Al Bilal and Majzoub Aidarous. The novel doesn’t follow classic literary form, it is neither a press report nor an autobiography, published by the Technical Committee of Meroe Dam, as he was assigned to write a novel as part of a research which studies the nature of the region and its heritage. In 2004, his work ‘The Human: Past and Present, the Man who was Displaced by the Meroe Dam” reflected the region’s ancient history, its people, its nature, and the present, and was approved by the Technical Committee.

Gezira Printing Press. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Gezira Printing Press. Photo credits: Mohammed Omer for Andariya

Most of his publications were initiated by friends, as Mr. AlFadul lacked the drive for publishing or the relentless pursuit of printing. He had a clear reason; the country did not present resources and financial support to enhance culture, science or literature sectors. Additionally, the Inqaz regime fought against culture, intellectuals and writers. Mr. AlFadul says that the complex issues facing a writer trying to publish his work and the bureaucracy of the non-institutionalized state distracts the writer from the creative process of writing. The fact that there is no entity appointed to print and publish for the public good is discouraging for a writer who is already dealing with the obstacles thrown his way. It is unfortunate to mention that no copies of his publications are available due to lack of publishing houses producing more copies.

Mr. Ahmed Al-Fadil says that the Sudanese writer is closed in on himself, and many factors drove him to do so. He thinks writers must be open to the world and develop writing tools through experimentation, openness, mixing with different cultures and increasing their knowledge. He hopes publishing houses will develop their ways and means, and conditions will be created by the post-revolution government to spark creativity and create the environment to aid writers to produce literary works that create waves locally and internationally to make Sudanese people proud. AlFadul also hopes his next novel can be published in a better environment.

This article is published as a part of a series covering how the Inqaz Regime shaped the Arts and Culture scene in Sudan over 30 years. The project is supported by the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, Arab Council for Social Sciences and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.