Images are curated through Rift Digital lab and Facebook pages of entities introduced in the article.

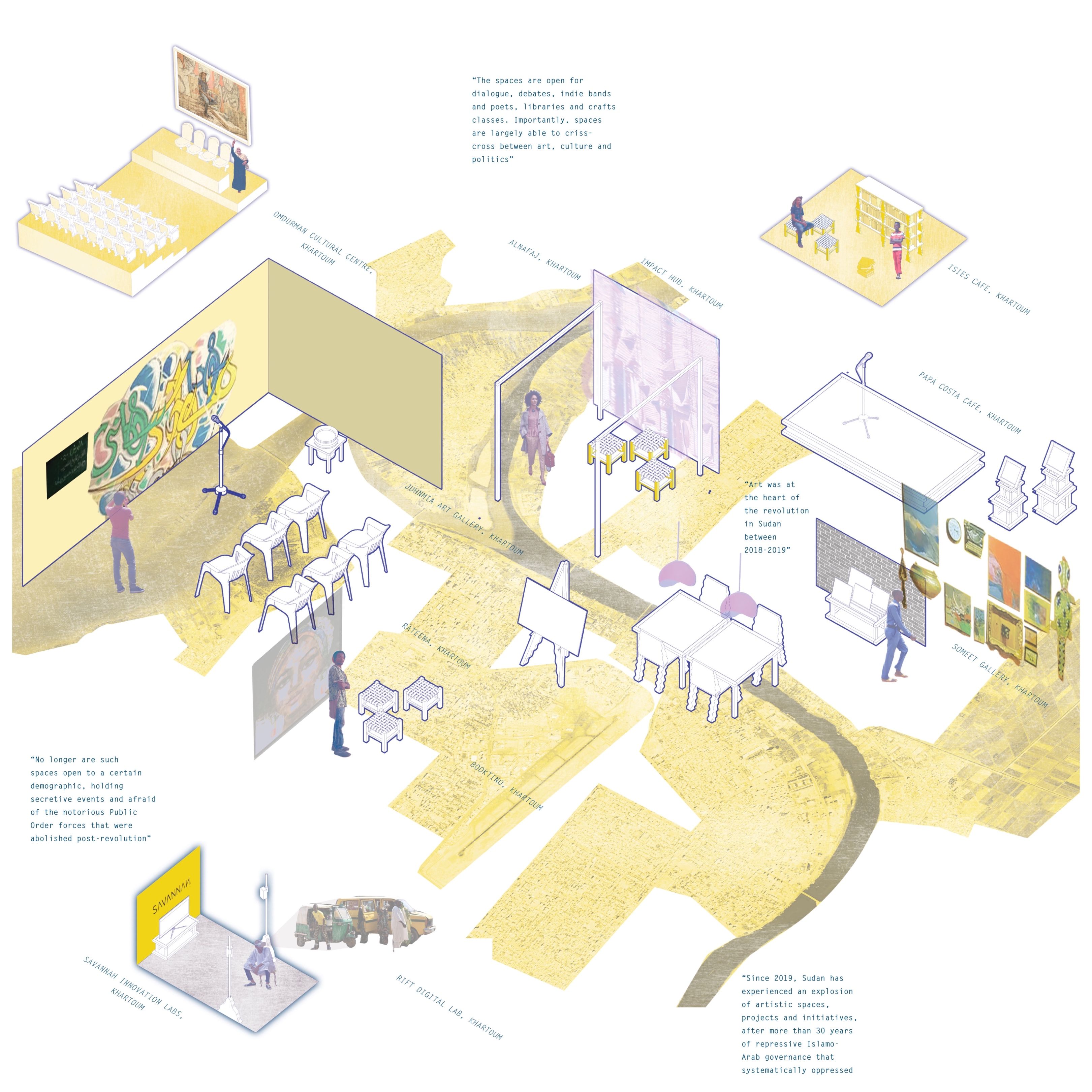

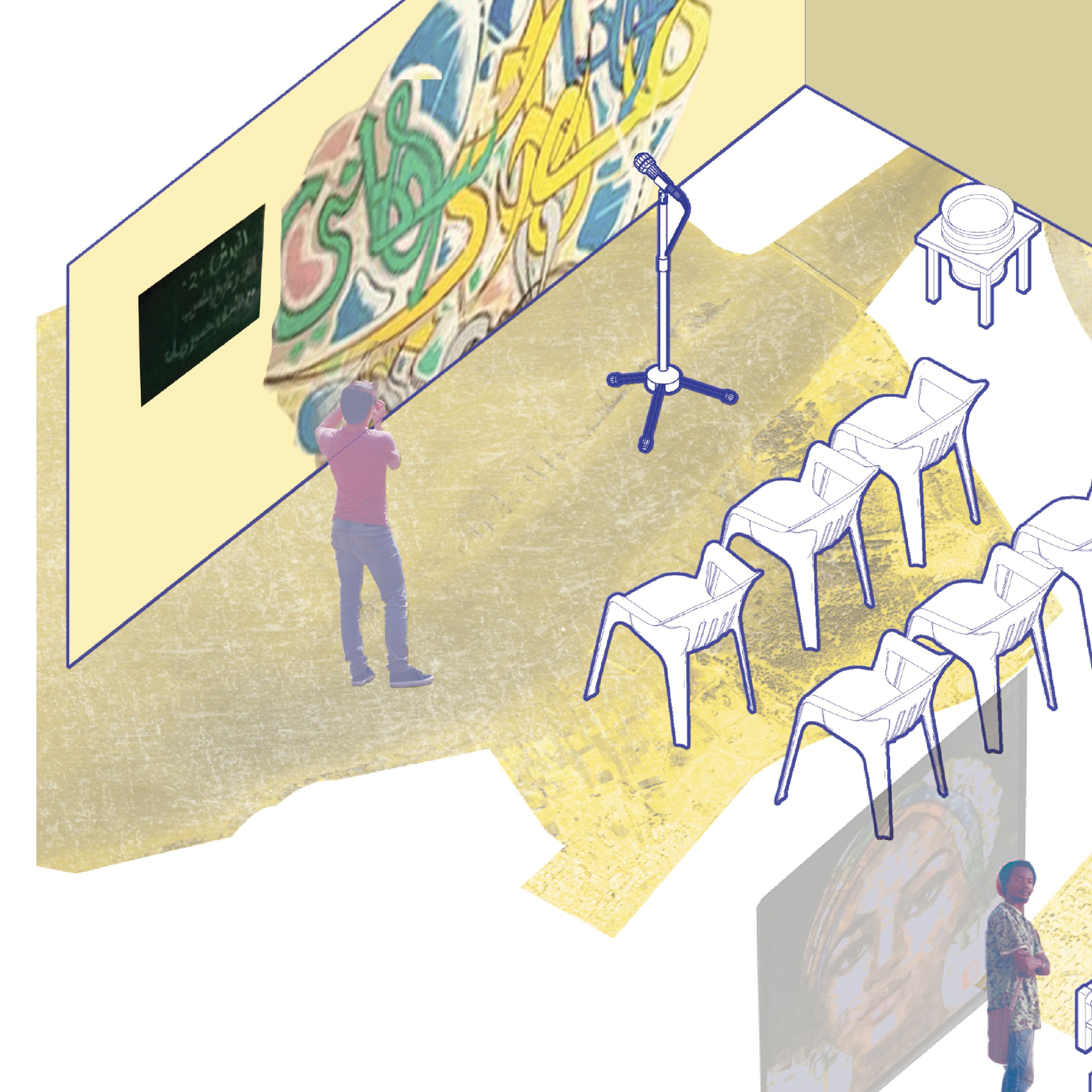

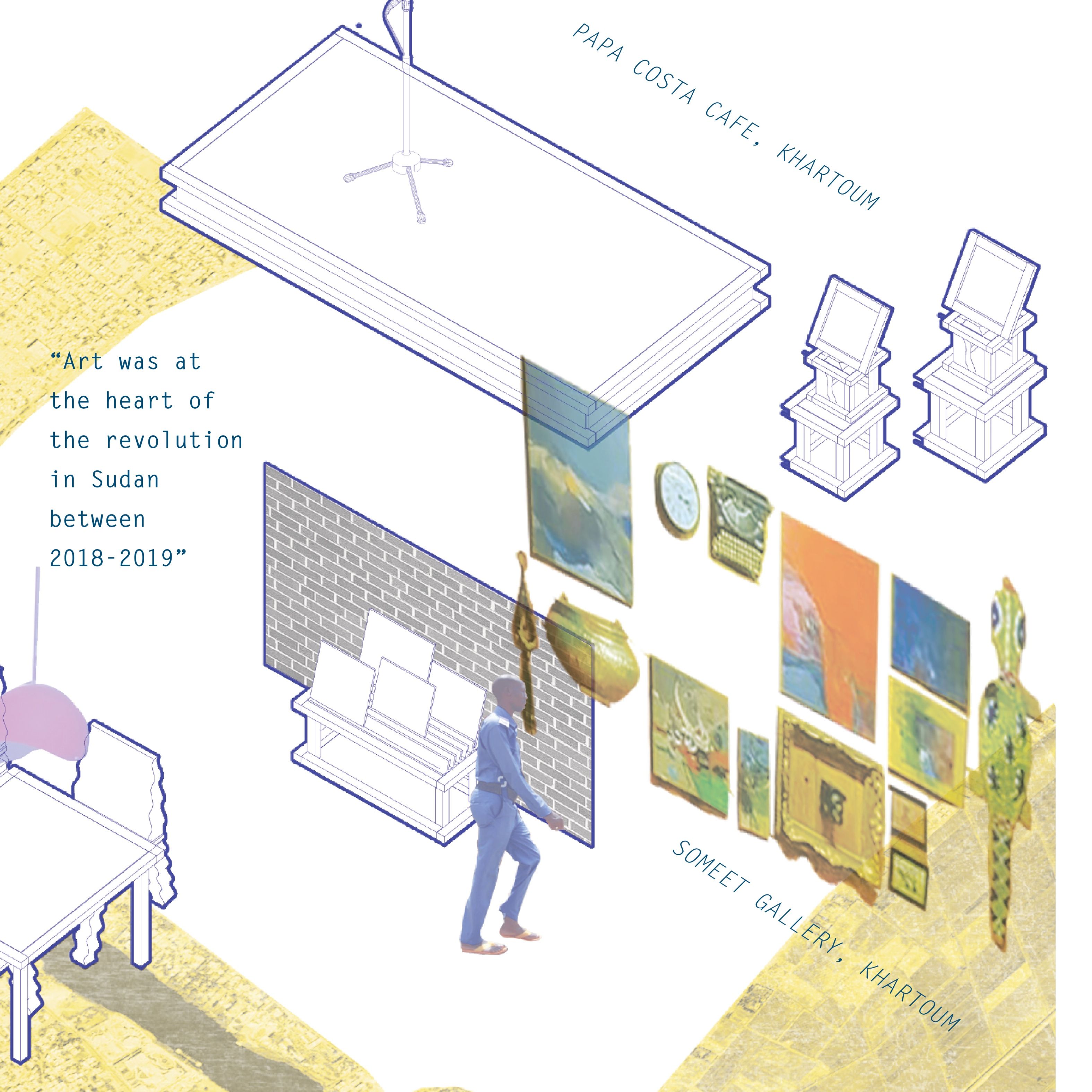

Sudan is going through a period of transformation: in 2018-2019 a popular uprising toppled a system defined by corrupt governance and injustice that had reigned for three decades. During the revolution, neighborhoods were strengthened with a renewed sense of organized work and collaborative action, consolidating networks of trust to build certain areas as safe spaces for people in tumultuous times. Art was at the heart of the revolution in Sudan between 2018-2019, with pop up events, mass concerts, poetry, music, graffiti and multidisciplinary performances taking over neighborhoods, along with the Qiyada sit-ins that popped up across different states between April and June 2019.

Since 2019, Sudan has experienced an explosion of artistic spaces, projects and initiatives, after more than 30 years of repressive Islamo-Arab governance that systematically oppressed arts and culture. Although the COVID-19 pandemic ground activities to a halt in some instances, 2020 and 2021 saw many more initiatives pop up due to more donor funding and general economic and political circumstances pointing towards Sudan’s rebirth and re-entry into global spheres. Once the COVID-19 lockdown was eased, the country’s socio-economic, security and political transitions sprang into action, and artistic players followed suit.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that Sudan is currently ruled by a partnership between a civilian government and the military, with few reforms underway for the authoritarian faction. This has caused multiple altercations, the most prominent being the Feed Arts case, where artivists were imprisoned for weeks following a neighbour reporting their theatre performance rehearsals. In this new wave of artistic hubs and cafes, many owners and founders, participants and staff are activists, making them easy targets for an oppressive authority that still lurks within the government. To date, the challenges are plenty. Sudan still faces security threats and frequent flareups, an economic collapse has gripped the country further over the last two years. Moreover, the government is not committed to any rehabilitation of the art and culture sector that was decimated by the toppled regime, neither through funding, material or formal support of grassroots initiatives taking shape. How does the sector then look in such times of uncertainty?

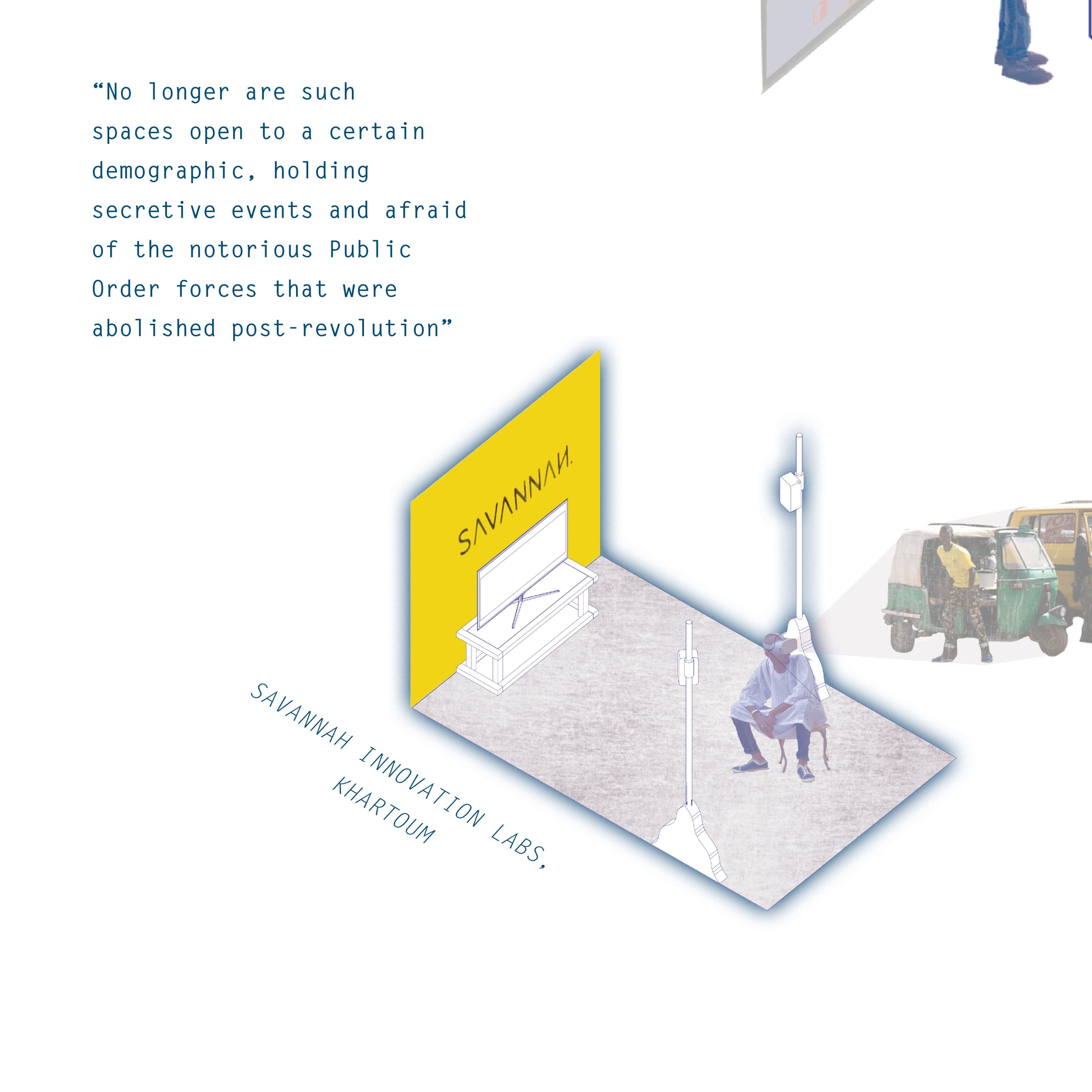

Cultural hubs, cafes and inter-sectional programs are not new in Sudan, but the spirit they are carrying now is different than during the Inqaz (previous dictatorship) era. No longer are such spaces open to a certain demographic, holding secretive events and afraid of the notorious Public Order forces that were abolished post-revolution. The spaces are now open for dialogue, debates, indie bands and poets, libraries and crafts classes. Moreover, spaces are largely able to criss-cross between art, culture and politics. Thus, cementing the importance of governance in youthful dialogues, and using modern and engaging tools to widen the net for discussing topics of importance to the current political transition in Sudan.

Cultural hubs, cafes and inter-sectional programs are not new in Sudan, but the spirit they are carrying now is different than during the Inqaz (previous dictatorship) era. No longer are such spaces open to a certain demographic, holding secretive events and afraid of the notorious Public Order forces that were abolished post-revolution. The spaces are now open for dialogue, debates, indie bands and poets, libraries and crafts classes. Moreover, spaces are largely able to criss-cross between art, culture and politics. Thus, cementing the importance of governance in youthful dialogues, and using modern and engaging tools to widen the net for discussing topics of importance to the current political transition in Sudan.

Breathing Spaces

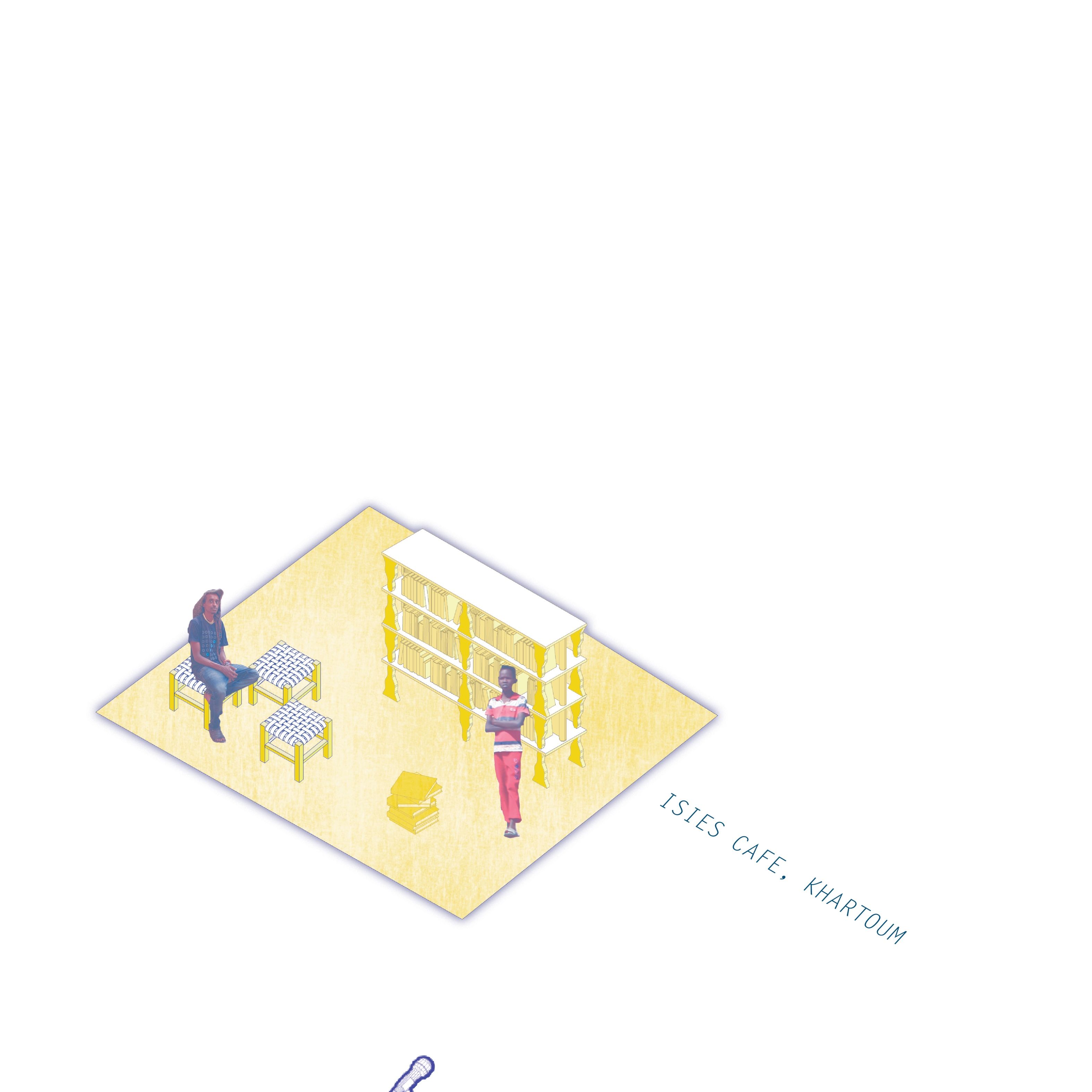

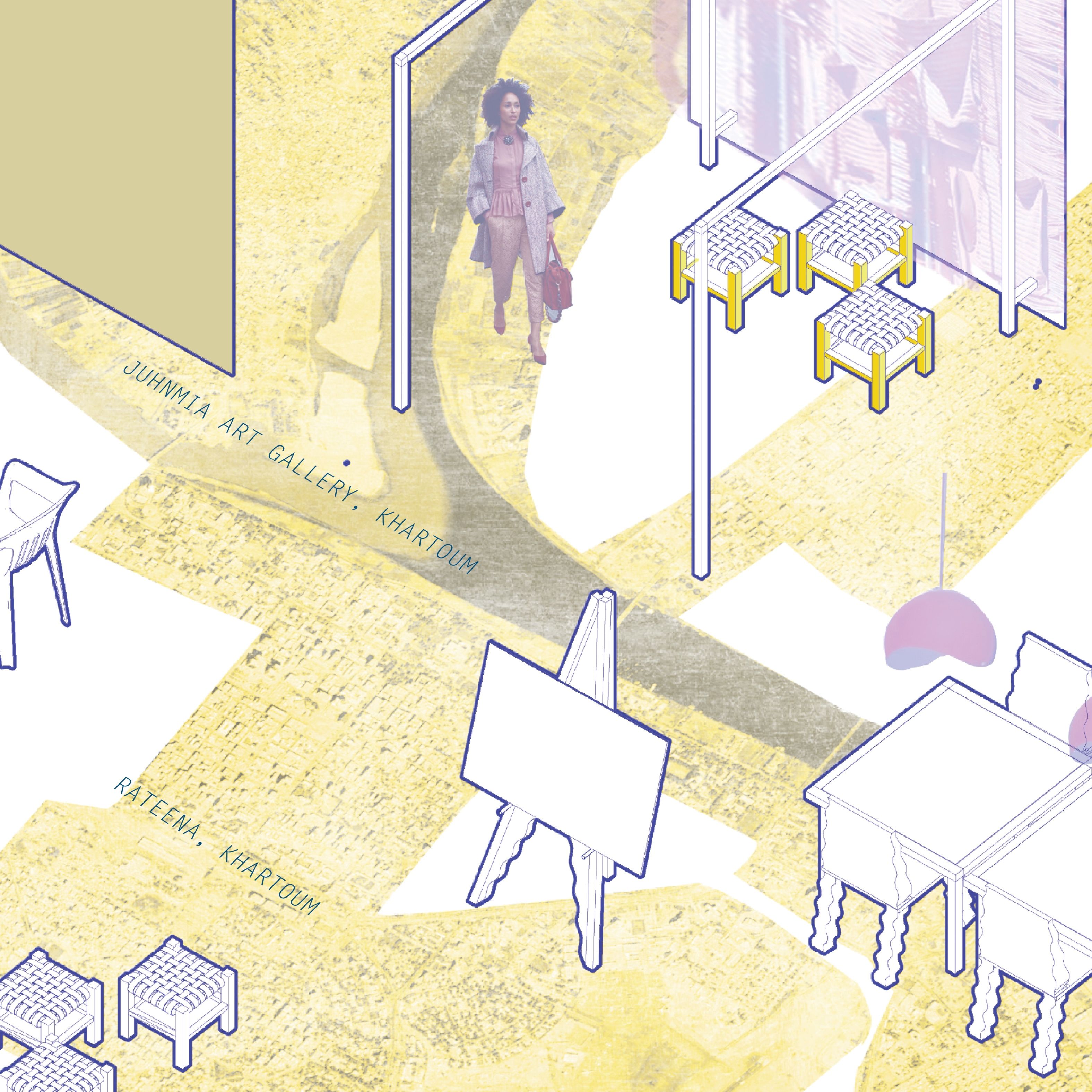

One of Khartoum's favourite and most iconic cultural cafes is Papa Costa in downtown Khartoum - largely favoured by the older millennial generation. The cafe still hosts events, but the area was largely abandoned when new hubs in commercial and residential sections popped up in the city. Cultural cafes opened by ambitious Sudanese youth continued growing, with Isies Cafe coming onto the stage by opening in the middle-class Sahafa neighbourhood, then expanding into upper-middle class Riyad, with a larger and more event-focused location. With Isies on the scene, many other cultural spaces and cafes became known for their cultural programming and identity. Some popular spots include AlNafaj in Bahri, Someet re-launched in Riyad (Khartoum), AlSutooh recently opened in Khartoum, Juhnmia (in Bahri), Booktino (literary cafe) in Manshiya and Rateena Cafe in Khartoum, which all flourished with a range of politically-flavoured cultural events.

For artists and activists alike, cultural cafes represent breathing spaces where they can meet like-minded people, debate ideas openly without fear of reprieve or raids, attend events and enjoy the comforts of a cafe and its food and beverage choices. As described by DT, a feminist and activist: “to me art cafes are breathing spaces for the general public to meet activists, who the previous regime painted as demonic, wrenched and stigmatized to the general public. The cafes became places where activists and cultural actors can meet openly to discuss and debate ideas and projects as well as network. They are also able to co-organize and enjoy cultural events and workshops, such as crochet or poetry, hosted by these cafes.” On a recent trip to Obeid, I came across Cafe Mocha where cultural players meet and mingle with those looking for a good cup of coffee. In Madani, cultural cafes and spaces are still popular for authors, filmmakers, theatre actors and more. The cafe culture, connected to cultural programming, is a great way for the sector to grow with the general public, healing the fraught interactions of the previous regime. They are also potential spaces for networking between different actors in the sector.

Nonetheless, the owners of such cafes are reporting many challenges related to finances, programming, and confronting the authorities. On confrontations, one interviewee who runs a cultural cafe stated “there were two RSF [Rapid Support Forces, a notorious and hated militia responsible for killings in Sudan and the Yemen war] soldiers who came and asked about who runs the cafe and they surveyed the customers. So I try to keep the volume low and keep a low profile as well.” To many, the sector is once again in danger of shrinking due to these recent challenges. Nonetheless, there is also growth for many who can weather financial challenges and avoid being politically profiled. One interviewee mentioned "there is still a lot of stigma building around stereotyping clients of cultural cafes. There is also another movement to counteract culture and feminism, and people who are visible in these spaces- such as excluding them from events and debates.” This movement is harming cultural cafes and reducing their ability to be resilient in the face of multiple challenges, all the while fighting social media rumors and troll campaigns. It is notable that a third of the cafes mentioned above are owned by women, putting them in a confrontational stance with many who are not comfortable with the opening-up of the arts and culture space and general abolishment of anti-freedom acts such as the Public Order Act.

There are efforts between cafes to coordinate events, but one interviewee mentioned the need for specific goals and coordination efforts to enable actors in the sector to battle issues as a unified front. Another potential for collaboration is unifying prices, salaries, rent, services and the quality and raw products used in such cafes that target similar demographics of clients. One interviewee noted “we have to work together because larger and more stable brands will eventually enter the market, shooting up prices for our customers. So we have to organize and build our quality and prices, making use of the current floated rates. We can also divide products that can use local raw materials and those that use international and imported products into price classes.”

What keeps them going? Many are settling into the business of running a cafe, enjoying the spaces they created that bring people together for cultural and music programming, as well as providing a good place for safe and open debates and discussions. One interviewee said “I have been working on this [project] since 2013 and I don’t think I can do anything else. The support I get is also great from friends and family to create a good environment and space.”

Art and Politics

When in 2017 the Impact Hub Khartoum opened its doors, it was a matter of time before other spaces and hubs started to open. In 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted two hubs from opening on time and launching their activities and programs fully: Savannah Innovation Lab and Rift Digital Lab. When they finally launched, they offered an interesting mix of art, entrepreneurship training and programs. Savannah Innovation Lab became known as an exhibition space, run by the Muse Multi Studios, a young outfit that curates art exhibitions and workshops. The space also hosts workshops and promotes the local entrepreneurship landscape by featuring founders and their projects. Rift Digital Lab organizes capacity building workshops in areas such as digital security training, as well as AR/VR exhibitions and creating content about creatives and their ideas and projects.

Hubs and spaces enable an open intermingling of art and politics in post-revolution Sudan. Many capacity building and events programs on arts and culture are being funded by major donors to include political debates, as is the case for Civic Lab, Adeela for Culture and Arts and Contraband . Previously, such spaces would not promote their politically flavoured events, and in most cases, their artistic events were also restricted. Moreover, political events for youth were not common, as most political debates were held at political parties headquarters or centers/spaces led by an older generation of academics or writers. The set-up (boring, little to no marketing, lecture-style) and the danger of police raids of such events left youth out of the equation. The openness of the new spaces and hubs led by youth for distinctly political events is a good sign of open dialogue in post-revolution Sudan. These spaces are on the rise despite the attack on the Feed Arts group in 2020 and ongoing protests about living conditions and insecurity across the country, along with government brutality and pockets of violence.

An activist who lives abroad and was recently in Khartoum commented that civic labs and hubs “ensure accessibility for all, not just activists. They are also relatively open and not harassed by the police, so there is a huge demand for such spaces post-revolution, especially for young activists.” He noted that there are still challenges such as poor infrastructure, poor customer service, service delivery, and low creativity. In particular, he thinks that host communities and neighborhoods do not feel happy about such spaces and their activities, creating an air of hostility that leads to police raids on account of disturbances or other issues - something often cited as the cause of the Feed Arts group arrest. Khartoum is not zoned and therefore commercial activities often happen in close proximity to residential blocks. This causes concerns and poses future challenges for hubs and spaces interested in expanding their programming. The spaces need to be accepted into the community and neighbors must feel the agency over the spaces, with the ability to benefit from spaces and co-exist in the same area. Another challenge such spaces face is the non-uniform taxation that occurs from different government agencies. These taxes can at times be increased without notice, disabling the spaces from managing their overheads and projections, and further threatening their start-up nature and limited funding.

Resilience Building in Times of Uncertainty

Although spaces are buzzing right now, a year ago they buckled under the weight of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rift Digital Lab’s staff were shocked into a frenzy when the total lockdown was implemented and even crossing bridges required permits - which the team did not have. The team had to find ways to transport their equipment to staff homes and move their work to remote settings. The Lab took time to figure operations out and discovered many processes that needed to be attended to, in order to make remote work smooth. Staff members also had to reorient themselves to this new reality, which was counterproductive to creative teams who are used to brainstorming and demonstrating work drafts in real-time, in a collective work environment.

For other hubs and labs that had grants and programs, they risked reaching the end of the grant without producing the deliverables agreed upon contractually. Although some activities were shifted to digital spaces, the effectiveness was generally considered to be low by both organizers and donors. Furthermore, commercially dependent enterprises suffered the most, as shutting down meant still having to pay for overheads and having no steady income, furloughing employees and waiting until the environment allowed for re-opening. Thus, during the pandemic, the entities with donor funding were more resilient due to donors' understanding of the circumstances.

The model that seems most fitting for cultural actors to remain impartial, have successful events, and still grow, is to build a hybrid model with multiple revenue streams, strong operational standards and procedures that are flexible and modern, allowing for talent acquisition and retention in times of hardship, in local and remote settings. Furthermore, hubs, spaces and projects need to confront the lethargic, incompetent, inefficient and analogue governmental methods and processes, topped with a layer of hostility left behind from the previous regime. In such an environment, it may seem that there is no hope for the founders and managers of such projects, but through three short case studies, we explore how they've solidified their projects and enterprises, and how sometimes failure is not permanent and rebirth is possible, despite the uncertainties. The case studies highlight the importance of resilience building, mutually beneficial partnerships, multi-disciplinary approaches and a plethora of changing environmental factors that impact day-to-day operations of the spaces and hubs.

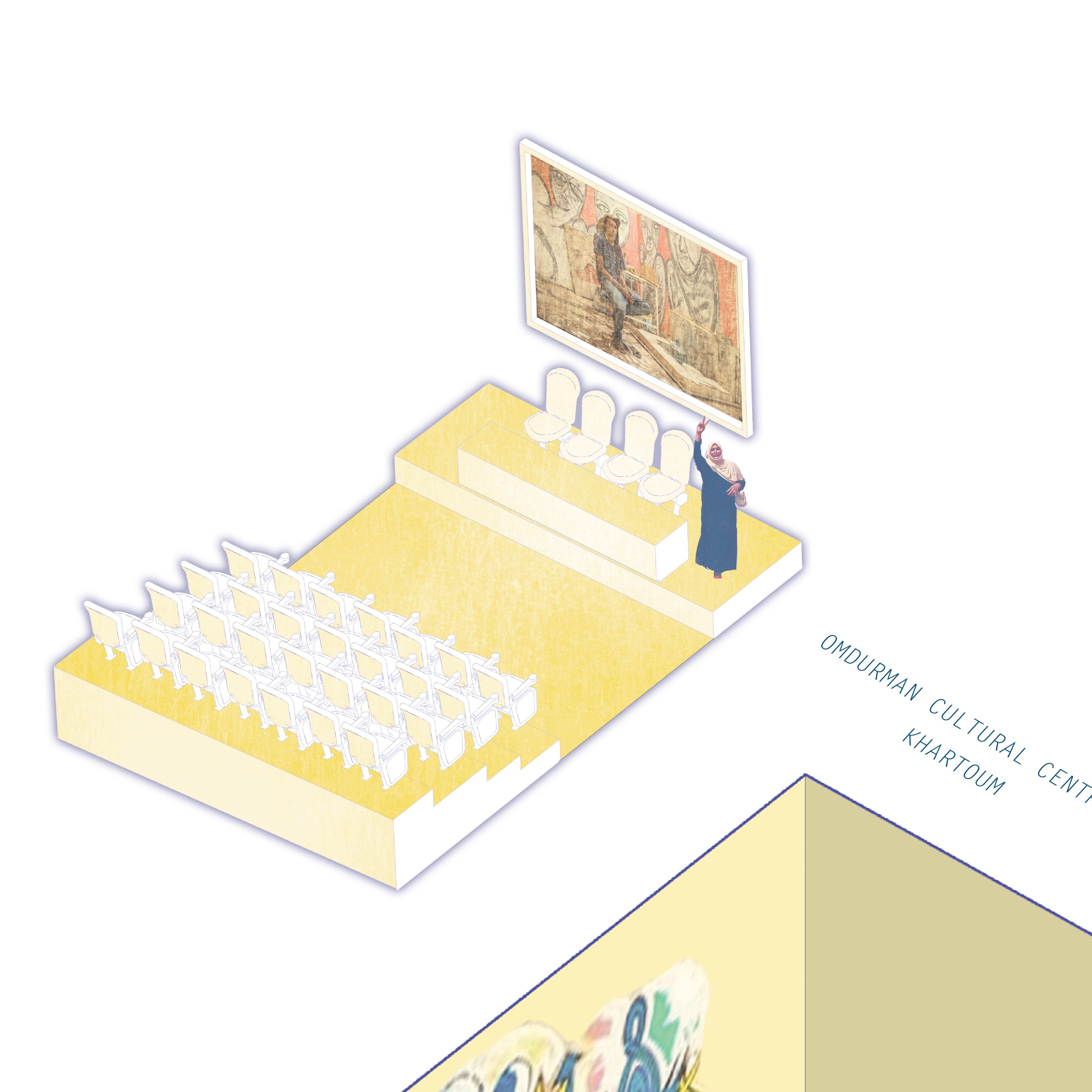

Case study: Omdurman Cultural Center

When the revolution in Sudan toppled the regime of Omer ElBashir, resistance committees in Omdurman occupied the large, central, and dilapidated Omdurman Cultural Center on AlMorada street. Today, the centre stands as a bustling spot with a calendar of public art events, drama rehearsals, student conferences and professional workshops for differently-abled communities in Omdurman. The center's approach was to vacate the premises through direct positive engagement with the resistance committees who occupied it during the revolution, maintain the building and its amenities through in-kind donations, and begin art and culture programming with different groups. Soon the centre was attracting drama groups, differently-abled groups, art and cultural practitioners, musicians, event organizers and many more.

The center's executive team established solid operational grounds with the Omdurman locality, where the centre is a governmental institution with independently run operations. By hosting different groups, being independently run, and improving on its amenities and facility, the OCC was able to attract donors and partners to co-create events and support groups who found a home there for workshops, rehearsals and art lessons. As it stands, stakeholders and actors in the sector (including the government, donors and partners) witnessed the positive progression of the centre in its current management and governance form, and are seeking to replicate this through a thorough and rigorous planning and knowledge transfer process between the OCC and other cultural centers around Sudan.

Case study: Isies cafe

Isies cafe was a favourite among many who like literature and music events, with its founder and owner, Weam Shawgi, being a cultural icon herself. This is until she was castigated by the community, and attacked and threatened by the authorities following a TV appearance where she debated ideas considered taboo and controversial to many. This was a personally and institutionally taxing time, as the second and larger branch in Riyad was forced to shutdown. Isies cafe was however revived with a new space in Khartoum 2, accessible to many, and hosted within a cultural centre.

The founder of Isies cited a list of multiple difficulties, at the top of which is economic hardship felt by the cafe and its customers. She stated "in the past, you could have events that can easily attract people. In Omak [branch] we used to add 20 SDG to the bill in 2018 for [live] Oud [music] events, so not all events had tickets. In 2021, it’s impossible to have an event without 500 SDG [tickets] and I was not able to give free coffee with that even.” Additionally, she noted that a 1000 USD profit was easily attainable in the past, but with the current inflation her profits stagnated at 200 USD if at all, and it was hard to keep a ledger, as costs accumulated and sprang out of no-where (municipality, maintenance, etc.).

In the current uncertain climate, running social enterprises is difficult for those who do not have the financial backing of investors or family support, without healthy revenues or projections. To come up with a new place and furnish it simply, Weam estimates the cost to be around 50,000 USD for a long-term lease. Based on her previous experiences, landlords have also not allowed tenants full agency over the space, especially for cultural spaces. There is an accumulated fear and trauma, due to wariness from experiences of frequent raids in pre-revolution Sudan.

Another layer of concern is customers themselves: although the social norms have somewhat loosened in Sudan after the toppling of the political-Islam rule, there are gray lines as to what is acceptable in terms of clothing and consumption of alcohol in public spaces. Nonetheless, spaces such as Isies offer safe havens for customers who are not always welcome elsewhere to share their beliefs and thoughts openly. Weam recalls activists in March 2021 advocating for women’s rights in a spontaneous speech in the middle of the cafe, sparking interesting conversations with non-activists and activists alike. Being owned by a self-proclaimed feminist, the cafe may have been a safer place than other cultural cafes for such discussions around women’s rights and feminism.

In June 2021, Isies announced closing once more and the future remains uncertain; will it be able to open again and find more hospitable spaces or will its model change? What we’ve seen is that Isies and its owner always find a way to come back, and their commitment to the cultural movement is laudable.

Case study: The Muse at Savannah Innovation Lab

Savannah Innovation Lab started with the aim of being a hub for entrepreneurship and startups. The Lab was challenged by COVID-19 which delayed its opening during the lockdown, but this provided a chance for realigning its mission with the SME sector needs. Today, the Lab is a hub for art and artistic expression, as well as a capacity-building space for civil society actors. Hosting multiple workshops every quarter and curating invigorating exhibitions set the Lab aside from other spaces in the Khartoum. Additionally, their capacity building exercises have spanned Nyala and ElFashir in Darfur, providing digital literacy training to small and micro-enterprises. Through monitoring and evaluation, the Lab is able to assess the impact of their training and enhance the modules further before scaling into other areas. Their approach is to decentralize capacity building and introduce a mesh of art and technology through the partnership with the Muse Multi Studios and international entities.

The Muse has brought art into the space by hosting multi-disciplinary art classes and training, offering artists an exhibition space and visibility to promote their work and find art collectors and buyers. The merger with Savannah has been instrumental to the Muse's growth, as it allowed for resource sharing for office use, events hosting and training venues.