Oil fields have a typical image that is commonly associated with them. Giant machines installed in odd locations. A deep, disturbing contrast between the man-made steely equipment and the sublime beauty of rainforests, meadows, deserts and oceans. For instance, in order for a drilling rig to be installed, a giant dent will be made in a forest; a space must be cleared for the machinery, the mud-pits, trenches and sometimes the accompanying camp. In doing so, a large piece of land is transformed from thick-bush cover and trees to a vacant dent of installations that are very unfamiliar to the environment.

A pipeline cuts through the land in the most unfashionable manner. The nastiest view you could notice in an open meadow is a beam-pump going up and down day and night, like a demon, with a huge storage tank near it. Well, at least nature-loving folks share this view, and perhaps hardcore environmentalists’ vehement opposition to oil is a combination of its carbon problems, and a protest against its repulsive aesthetics.

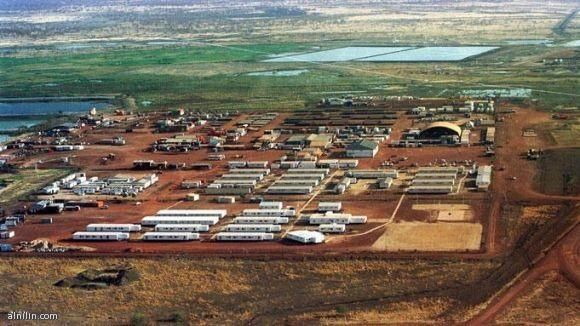

The main oil extraction station at the Heglig oil well near Bentiu in Abyei, South Sudan. Source: AFP

Interestingly, there is another beautiful side of oilfields that is impossible- or at least very hard- to grasp for an outsider. The people who work in this industry, particularly those who work in field operations, know this side very well; I have been fortunate to experience it as an insider.

There are many oil fields in Sudan, in the Western and Southernmost parts of the country, and I have been to almost all of them. One common aspect of these places is the sense of harmony and collaboration between communities nearby oilfields and the oilfield community itself. I will never forget the Meerkat families that come to the basecamp at exactly 6:00 pm sharp for the mealtime. Nonchalantly, they arrive as if they were a staff of the company. Birds will come looking for the extra food thrown every day by catering coordinators.

Smiling Meerkat. Source: Pinterest

Standing on a rig floor, you can see a number of birds utilizing the high, vertical structures of derricks and storage tanks. Oilfields normally have nearby water wells that local communities get their water supply from, as part of the social responsibility programs that operating companies commit to. The sight of local communities getting water supplies for themselves and their cattle is very satisfying. A sense of pride envelops you as you remember being yourself part of the very workforce that drilled that water well.

The insiders abhor the bad side of oilfield operations as much as they celebrate the bright sides. The plastic sheets of mud pits that do not decompose, the flare stacks that kill thousands of flying insects at night, and chemical spills that negatively affect biodiversity are very unwelcome. Oil companies must invest more on research and development to find innovative solutions for these problems, and construct strong policies to protect the environment.

It is also unfortunate that work sites are so noise-averse that it is almost impossible to enjoy the serene, soothing sound of the forest at night, since it is either that you are inside of your sound-proofed dull cabin, or out for the humming machines and buzzing motors. No chance for meditation and introspection.

Recounting my experiences as a worker in the oil patch, I joyfully reminisce about the herds of Racoons registering their daily visits to our basecamp. I remember the nomads of Heglig in West Kordofan, whom the scarcity of resources could never deter, and whose diligence and intelligence explains why they can still thrive in those harsh environments. I remember how they traded their valuable products with us, how they utilized whatever the oilfield offered to sustain comfort for themselves and their cows, sheep and goats.

The times when the giant Marabou Stork birds with weird bags under their necks (locally named Abun-khareeta) used to come over every afternoon near Sharif Oilfield in East Darfur were good ones. And the local football community in that area was very welcoming of the workers. These are but a small portion of what the oilfield offered, but our seniors have tales that stun belief! I would argue that their experience- the human experience- was more impressive and more inspiring than what they have achieved technically. For, at the end of the day, a worker can barely recognize his/her contribution to the national economy, but a small interaction with the people of an area will forever be stuck in that worker’s mind.

War-time Woes

Unfortunately, many fields have been affected by the ongoing war in Sudan, with some of them, especially the fields of East Darfur, have been rendered obsolete; they will have to be reconstructed from scratch if they are ever to resume production again.

Sufyan Oilfield: oil storage tanks burned down after an RSF attack on SAF security of the field. Source: Omder Times

Balila Oilfield in West Kordofan was looted by RSF personnel and later by other locals, the same occurred in Sufyan Oilfield which was looted and completely destroyed. Even the only oil refinery in the country- having been occupied by the RSF- was hit by air-strikes multiple times by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), making many facilities in it out of service. Initially occupied by the RSF, intense fighting had taken place near the refinery for almost a year until later captured by the SAF. Aftermath footage has shown a great destruction of its infrastructure, with an estimated USD $ 1.3 billions of losses in facilities.

Air strike aftermath in al-Gaili Oil Refinery, Source/al-Rakoba News

Compounded Losses

The oilfields, though scrutinized by many as failing to realize their social responsibility commitments, have been hugely beneficial to local communities. I was born in a village in East Darfur, which is the nearest to Sufyan oilfield. Since exploration began in 2003, when I was barely 6 years old, and up till 2023, there has been significant development in my village and the nearby villages and small towns.

More water wells solved the problems of water scarcity in the summer; especially for cattle owners. More access to fuel, such as diesel, made it cheaper for farmers to rent agricultural equipment such as tractors, planters, balers and harvesters; and it also reduced transportation costs for final crop yields.

Additionally, there has been a reliable cellular network throughout the first months of the war when other places in Darfur suffered immensely from poor connectivity. Moreover, the employment opportunities for the local youth were decent. All of these benefits were gone the day the RSF decided to attack the oilfields. “All services are lost, we are suffering consequently because of this mess,” Hayder, a resident of the village, told me.

Wars bring with them nothing but destruction, and what happened to the oilfields in Sudan is just a tiny fraction of the now-tragic reality of the country. Economic losses are inestimable. We hope that peace takes place, so that we can rebuild our oilfields again with more environmental care and better social responsibility programs. The once-vibrant sector of the country must not be gone with the wind.