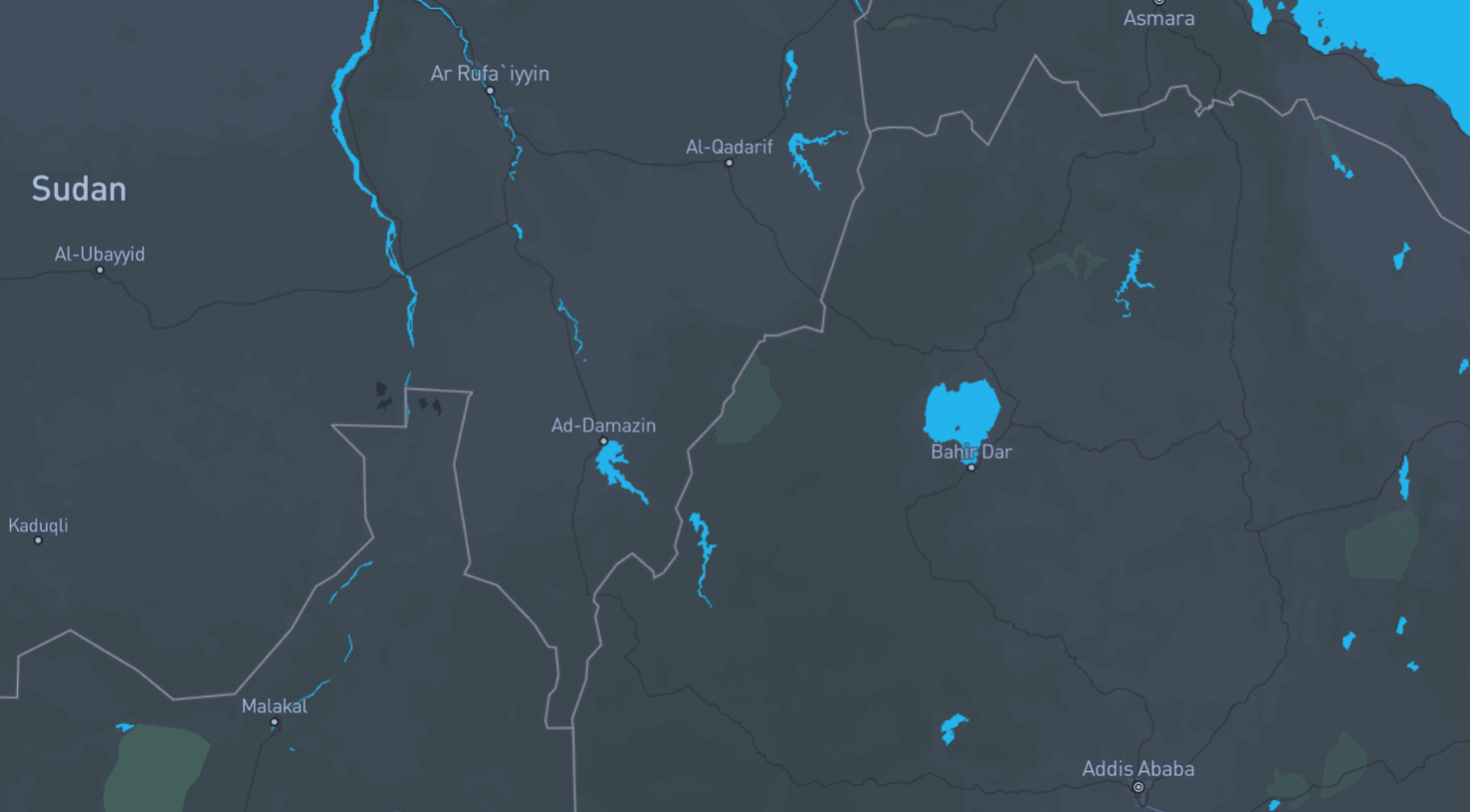

A map for the Blue Nile Basin

Introduction

On the 2nd of April 2011, the foundation stone of the largest water dam on the African continent was laid by the then Ethiopian Prime Minister, Meles Zenawi. Thus, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) was born.

The dam cost Ethiopia $4.6 billion and is located just fifteen kilometers away from the Sudan-Ethiopia border. In February 2022, the dam started producing electricity and when it reaches full capacity, it will be able to produce 5,150 megawatts of electricity.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) could assist Sudan in the growth and improvement of its electricity, economy, and agriculture in the long run, if Sudan and Ethiopia cooperate to manage the dam. According to a 2021 research paper by the Masinde Muliro University of Science & Technology, up to 500,000 hectares of land can be irrigated in Sudan due to the impact of the GERD. This is almost 10 percent of the total suitable lands for irrigation in all of Sudan, as calculated by the Nile Basin Initiative, an intergovernmental partnership of 10 Nile Basin countries.

The flow of the Blue Nile river is expected to become steady, according to a research paper published in May by the University of Waterloo. This will improve irrigation in Sudan and help increase Sudan’s GDP up to USD $82 billion, if collaboration between Sudan and Ethiopia happens in the context of irrigation and cropping patterns.

However, these positive impacts will only be seen in the long term when the dam is fully operating, according to the research. During the construction phase, the GERD is expected to decrease Sudan’s hydropower generation and irrigation supply reliability. People who depend on floods recession for their agriculture won’t be able to maintain their crops properly, which is an immediate effect in the short term from the GERD.

Since 2011, the three countries of Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan have engaged in various talks, dialogues, and diplomatic visits to negotiate specifics around the filling and operation of the dam. Unfortunately, government officials have so far failed to reach an agreement that satisfies all three countries.

Sudan seeks to ensure that its dams on the Blue Nile won’t be affected, either by low electricity produced or the possibility that floods could drown and destroy the dams if the GERD was to malfunction or be destroyed. Also, millions of people in Sudan are at risk of famine and food insecurity, so any impact on the crop yields due to a decrease in the water flow or the fertilizing elements that the Blue Nile river carries would be an unwanted outcome.

Six years ago in a TV interview, Ahmed Al-Mofti, an attorney and a former member of the Sudanese delegation in the GERD negotiations, said: “Ethiopians intend to make the GERD as a water bank. They want to hold the water of the Blue Nile and sell it to Sudan and Egypt. And Ethiopians did say they will provide Sudan with electricity, but they didn’t say it was going to be for free.”

Ethiopia filled the GERD regardless of these unresolved issues with Sudan and Egypt. The dialogues and talks were held in various geopolitical landscapes: sometimes in one of the three countries related to the Blue Nile: Sudan, Ethiopia, or Egypt, and sometimes in other African countries with or without the support of the African Union. Also, the issue escalated to an international level and a session in the UN Security Council was held specifically to address the issue of the impact of the GERD on Sudan and Egypt.

Impact of the GERD on Sudanese Dams

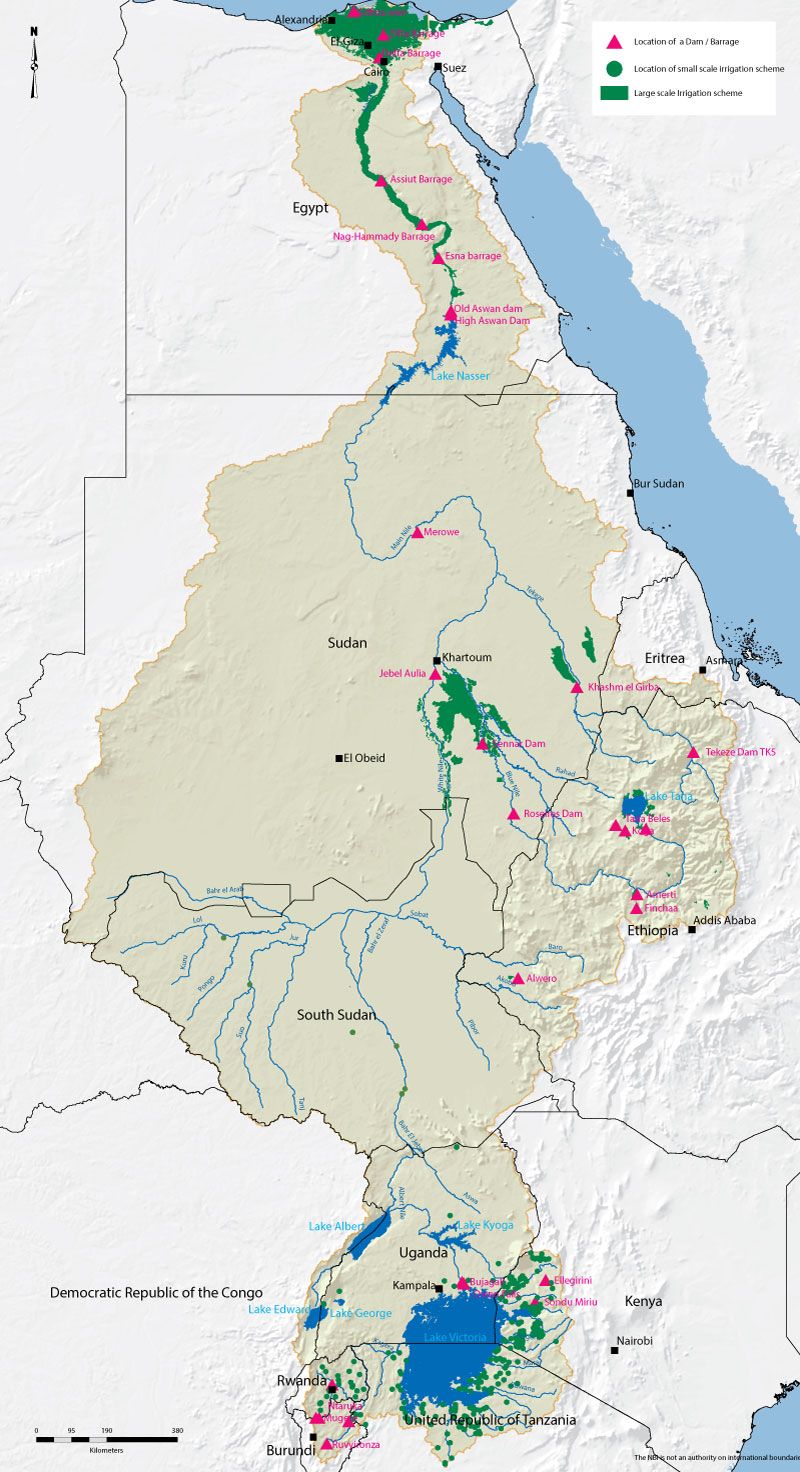

Hydraulic Infrastructure in the Nile. Source: Nile basin Water Resources Atlas

According to the Nile Basin Atlas, there are five dams built on the Blue Nile and its branches: three of them in Ethiopia and two inside Sudan. The two Sudanese dams are Roseires dam and Sennar dam.

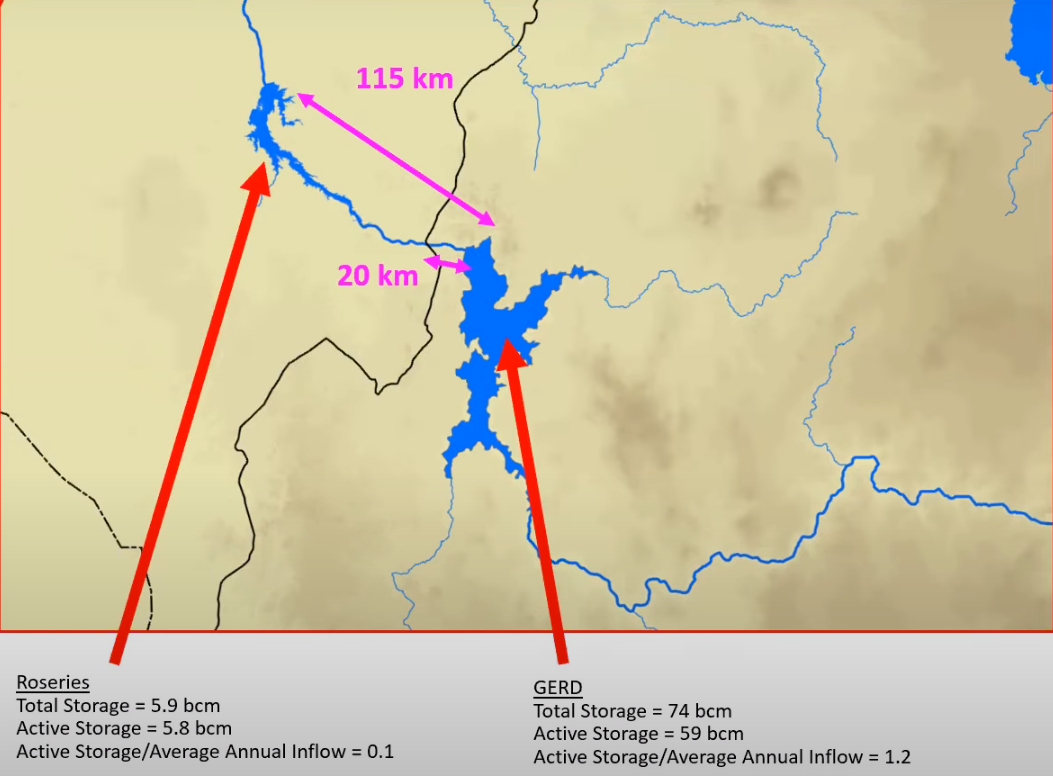

Dams on the Blue Nile. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iqLuBcwITE&list=PLnjnIV1H5-zQZ9Yk8eOvbi4eCKfdJO9de&index=37, Kevin Wheeler, University of Oxford, during a lecture in the Nile River Basin Crisis Webinar Series by the UCLA African Studies Center and Samueli School of Engineering

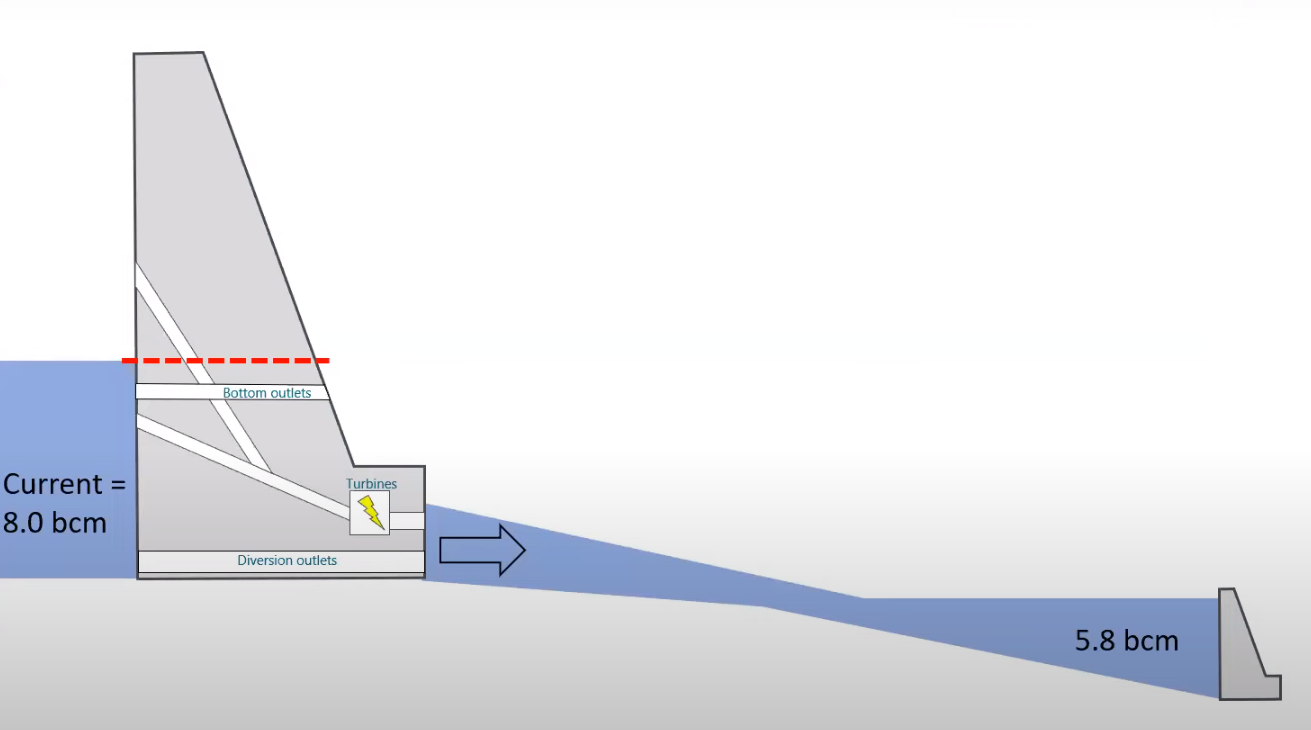

Size of GERD (on the left) and Roseires Dam (on the right) and their capacities. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iqLuBcwITE&list=PLnjnIV1H5-zQZ9Yk8eOvbi4eCKfdJO9de&index=37

The Roseires dam is threatened to be flooded by the GERD, according to some experts including Dr. Kevin Wheeler, an Oxford Martin Fellow at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, U.K. The Roseires Dam has to be capable of holding the water coming from the GERD or be able to release water at a particular pace that’s coordinated with the GERD to avoid any kind of calamity: a reason why cooperation between Sudan and Ethiopia is critical.

Impact of the GERD on Farming in Sudan

The water of the two Niles is mainly used in producing electricity and irrigation. However, Sudan has a variety of farming systems and also uses rainfall for farming. In the long term, the GERD is expected to increase the available water for irrigation in Sudan, but it is expected to negatively impact irrigation in the short term. According to FAO, the main farming systems that are used in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin are dryland farming, irrigational, agro-pastoral, and pastoral. Dryland farming is associated with areas of drylands that are farmed during cool wet seasons. Agro-pastoral is a form of agriculture that mixes between growing crops and raising livestock. Pastoral is only focused on livestock.

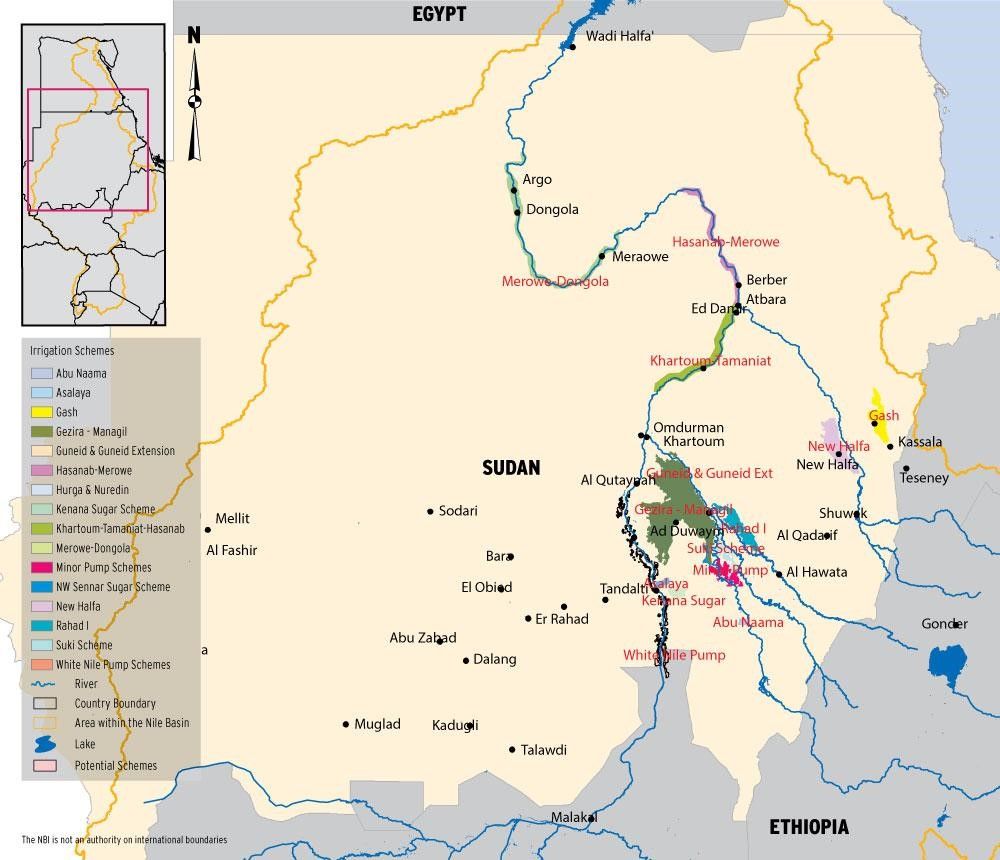

The irrigation schemes in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin include minor pump schemes, Asalaya, Rahad, and Managil in Gezira - which is the largest irrigation scheme in all of Sudan.

Map of Irrigation Schemes of Sudan

Irrigation schemes in Sudan. Source: https://atlas.nilebasin.org/treatise/irrigation-areas-in-sudan/

According to the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) strategic water resources analysis, there are 25 irrigation schemes in Sudan and the area that these irrigation schemes occupy increased from about 1.8 million to two million hectares between 2015 and 2018.

NBI projected that Sudan will expand its irrigation schemes to roughly three million hectares by 2050 using either “planned development scenario” or “business as usual scenario.” The Business as Usual scenario, according to Nile Basin Initiative, is a scenario for future patterns of activity which assumes that there won’t be any significant amends that will affect the current path of irrigation development. The planned development scenario refers to developed irrigation master plans by the government or other players.

Maximizing rainfed agriculture along with supplemental irrigation can be a cost-effective solution to achieving food security, according to NBI. Some studies indicate that such a strategy can contribute up to 75 percent of food production by 2025 while using fewer resources.

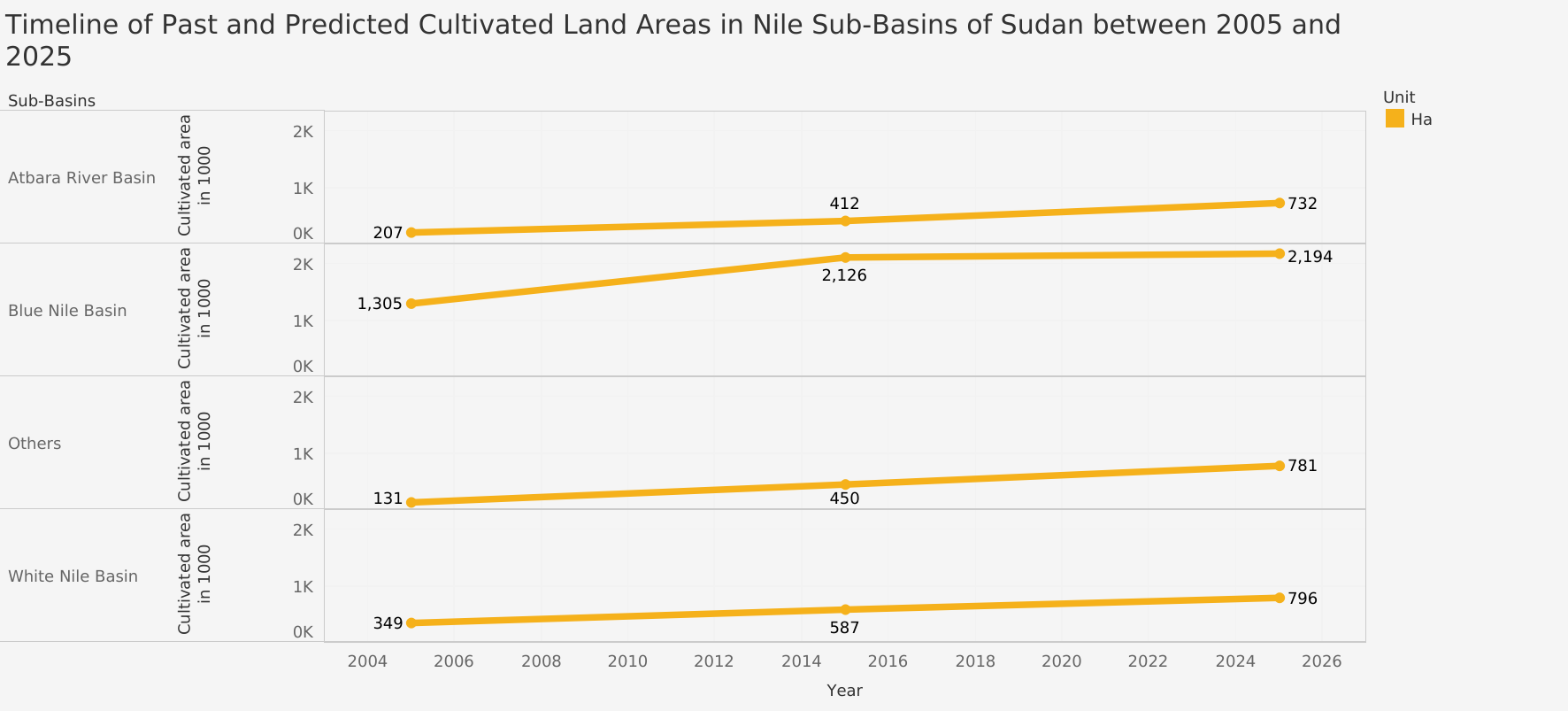

Table of past and predicted cultivated land area in Nile Sub Basins of Sudan. Source: https://nilebasin.org/index.php/information-hub/technical-documents/128-irrigation-development-projection-in-the-nile-basin-countries-scenario-based-methodology/file

Check out the interactive visualizations on Andariya's Tableau: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/andariya.platform/viz/CultivatedAreasinNileSub-basin/CultivatedAreas

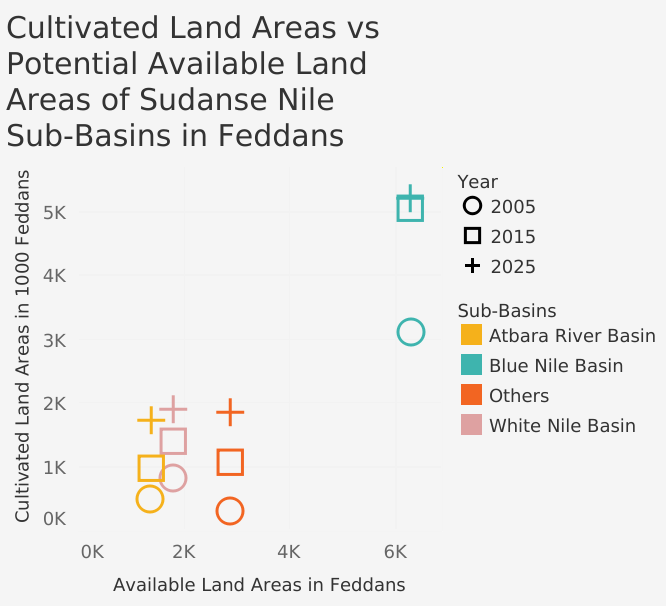

The data visual above shows which sub-basins are expected to increase at the highest percent, and which sub-basins provide the most irrigational areas in the future for Sudan’s agricultural projects. The largest land areas to be cultivated for agriculture are provided by the Blue Nile Basin, which constitutes 44.56 % of the total land area to be cultivated in 2025.

“On balance, the impacts for Sudanese agriculture will be positive. The regulation benefits for irrigated lands will vastly outweigh the costs of lost recession agriculture. However, it should be noted that increased water use in Sudan for irrigation purposes (made possible by the flow regulation provided by the GERD) could lead to tensions downstream, with other farmers in Sudan as well as with Egypt, and so any expansion of agriculture area must be carefully managed. One should expect the impacts on agriculture (both negative and positive) to occur very soon. For support of existing irrigation in Gezira (positive) and impacts on recession agriculture (negative), for example, as soon as the GERD begins to regulate flow. This will be relatively soon, if not already occurring. But the long term impacts will be more positive, because those who were involved in recession agriculture will adapt and take on new activities, and the GERD regulation should allow some irrigation expansion in existing and new areas. This more positive shift will become more obvious once the GERD filling is complete" Marc Jeuland, an Associate Professor in the Environmental Science & Policy Division from the Sanford School of Public Policy told Andariya.

Link: https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/andariya.platform/viz/CultivatedAreasinNileSub-basin/CultivatedvsAvailable Source: https://nilebasin.org/index.php/information-hub/technical-documents/128-irrigation-development-projection-in-the-nile-basin-countries-scenario-based-methodology/file

There are two water applications for irrigation in Sudan: long furrow basin system and level furrow basin system, which depend on creating channels in the ground that are then flooded with water. The long furrow basin system is functioning efficiently, with an overall performance of 68 percent to grow sugarcanes, according to Nile Basin Initiative, whereas the level furrow basin system performed with an efficiency of 75 percent and was the predominant system adopted by most of the irrigation schemes in Sudan- including its largest scheme, Gezira.

However, the Gezira irrigation scheme only yielded 50 percent cropping intensity, which is due to two factors: poor management of irrigation water at the field level, and the fact that the water isn’t delivered in the right quantity at the right time due to the catastrophic canal condition that’s infested with weeds. The Nile Basin Initiative recommended that Sudan should benchmark best irrigation practices in its irrigation schemes, especially Gezira, in order to achieve greater results in agriculture.

The GERD is expected to improve irrigation in Sudan by regulating water flow and increasing storage capacity of Sudan’s dams, requiring less maintenance of dams and irrigation canals, reducing sedimentation, and increasing recharge of underground aquifers, according to a 2021 presentation by researchers at the University of Khartoum.

However, it is also expected to cause negative impacts by decreasing flooding irrigation, increasing the risk of over-flooding in the case of extreme rainfall in Ethiopia, and increasing land degradation due to the loss of sediments naturally carried by the river.

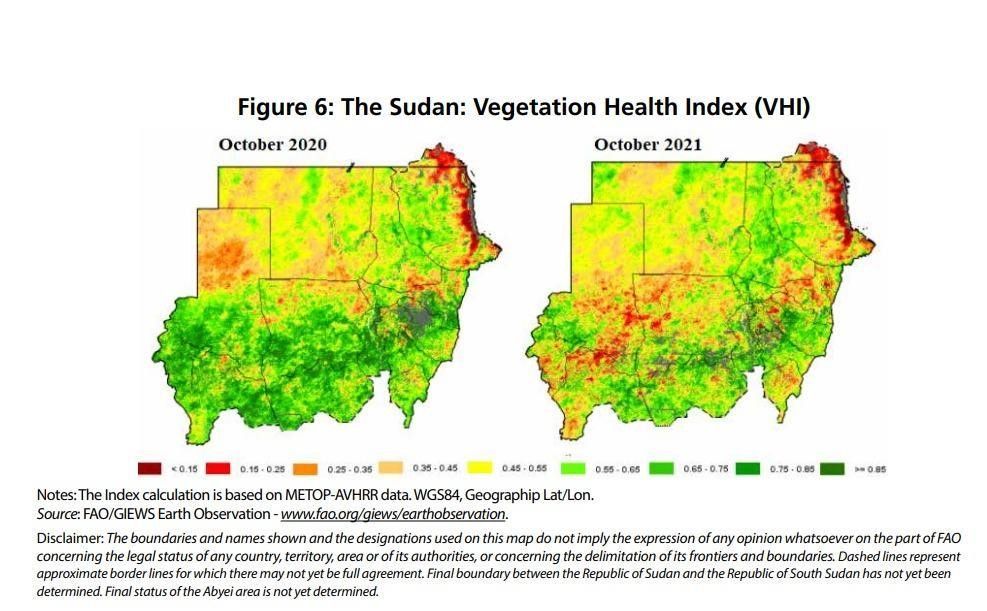

Vegetation health index. Source: https://www.fao.org/3/cb9122en/cb9122en.pdf

The Sudanese Blue Nile Basin vegetation health index worsened after the second filling of the GERD as shown in the map above in the states of Blue Nile, Gezira, and Sennar. The Sudanese Blue Nile Basin is around 111,237 square kilometers, which constitutes 5.89% of Sudan’s total area.

According to the Nile Basin Initiative, most of the soil in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin is either moderately or highly suitable for irrigation. Sudan has roughly around 5.2 million hectares of suitable land for irrigation, as calculated by NBI. Most of the Blue Nile basin in Sudan is utilized for crops and also includes grasslands and tree-covered areas. Minor parts of the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin may suffer from moderate drought or abnormal drought in times of winter, but during most of the year, the region is extremely wet.

According to the FAO, most of the crops produced declined since 2018 due to many factors, including lower rainfall and less efficient irrigation. Most agricultural inputs like seeds, fertilizers, herbicides, and labor were inadequate. Agricultural machinery was available, but the expenses of maintenance and spare parts were high, and the spare parts were of low quality. Fuel costs were also very high.

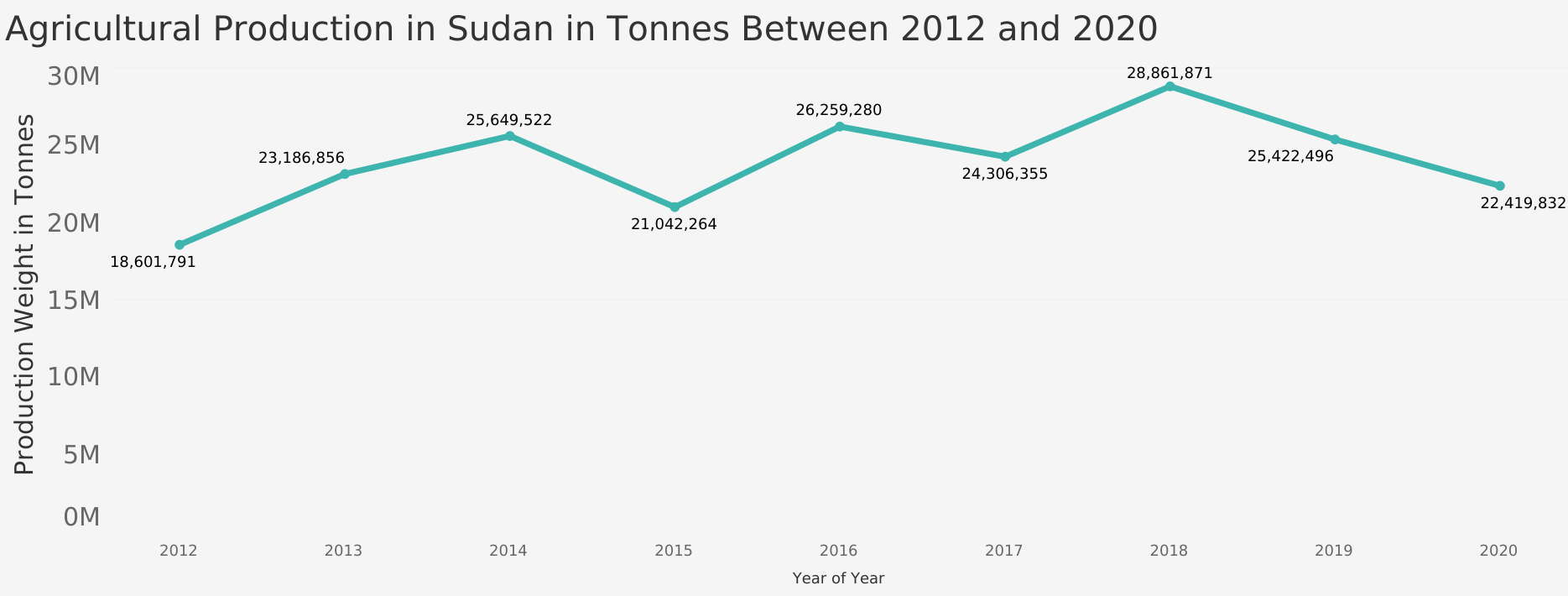

Source: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL

The crops grown in Sudan include hibiscus, wheat, corn, banana, peanuts, cotton, millet, sorghum, gum Arabic, sunflowers, sesame, and beans. The most grown Sudanese crop in tons according to the FAO is sugarcane, but the crop that occupies most of the Sudanese farmlands is sorghum.

Sugarcane has especially suffered a decrease. In 2020, the year of the first filling of the GERD, the harvest declined from 532 to 461 tons. And in 2021, the year of the second filling of the GERD, the harvest decreased even more to 349 tons. These are the weights of sugar production by three major companies in the industry: Sudanese Sugar Company, Kenana Sugar Company, and White Nile Sugar Company.

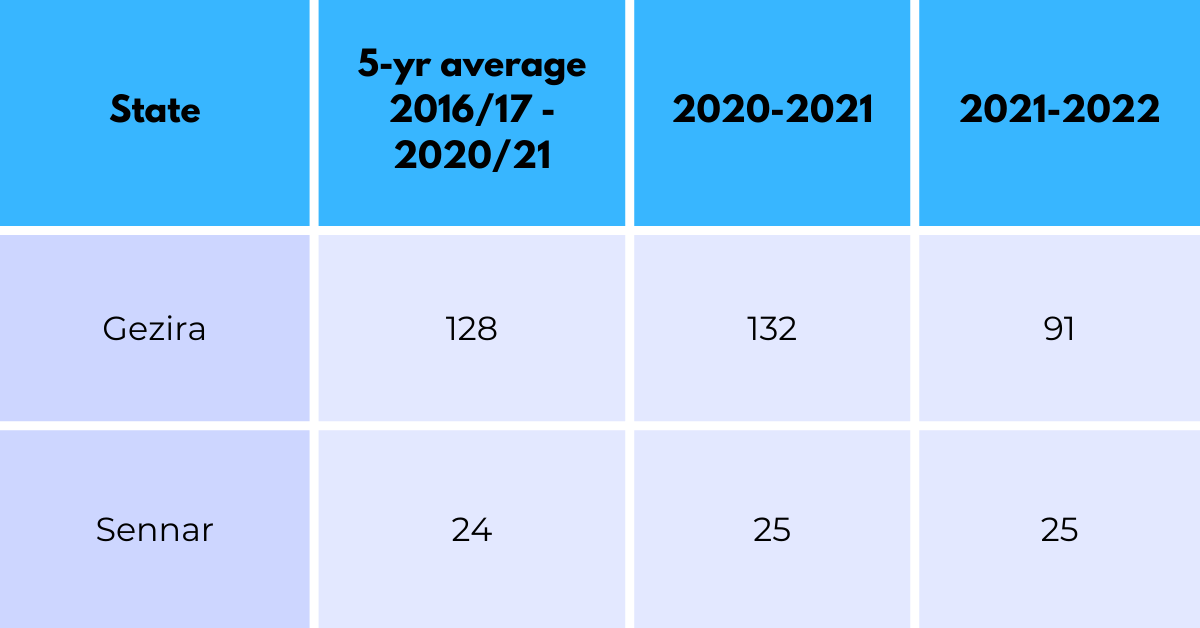

Area of sorghum harvested via irrigation schemes in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin in (‘000 hectares):

According to the table above from the FAO (page 19), the area of suitable lands for irrigation in Gezira used to grow sorghum, which is the most widespread crop in Sudan, decreased after the second filling of the GERD in July 2021. Some of the reports and studies show that the immediate impact of the GERD on agriculture in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin would be negative, especially along the banks of the river.

“There are two distinct types of impacts, one positive, and the other negative. My view, based on modeling work and some prior data collection, is that on balance, the impacts on Sudanese agriculture will be positive.

- Positive impacts on existing pumped surface water irrigation systems and irrigation system expansion along the Blue Nile. The GERD will stabilize flows throughout the year, ensuring a more consistent supply of water for Sudanese irrigation systems than was previously possible, even with the heightening of the Roseires Dam. This is because there is much more storage and regulation provided by the GERD, and Ethiopia will want to ensure a stable release pattern to continuously generate hydropower. A related benefit is that the GERD will trap a great deal of sediment which is difficult to manage in Roseires and Sennar, and which creates problems for canal-based irrigation systems in Sudan. This problem of sediment will be mitigated considerably, though soil quality will need to be monitored carefully.

- Negative impacts on existing flood recession agriculture along the banks of the Blue Nile. Though this does not constitute a large area of irrigation (especially compared to the benefit noted above), some people depend heavily on flood recession agriculture in Sudan, and this practice will no longer be viable once the GERD operates normally. Efforts should be made to provide alternative livelihoods for those affected" Marc Jeuland, an Associate Professor in Environmental Science & Policy Division from the Sanford School of Public Policy, explained to Andariya.

Source: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL

Source: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL

Compounding Impacts: The revolution, a Pandemic and Climate Change

Yet, it’s very rash to label the GERD as the main reason behind all of the calamities that agriculture in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin has suffered from. It’s well known that Sudan endured a volatile political status since late 2018 that didn’t calm until the agreement between the military and the civilians in August 2019, which afforded the country a little calm before things escalated in various areas again, culminating in a military coup on the 25th of October 2021.

The Sudanese revolution brought many advantages to the economy of Sudan that in turn reflected positively on agricultural businesses and farming in general as the value of the national currency started to stabilize. But since the military coup of the 25th of October, 2021, Sudan has returned in many aspects back to the era of economic sanctions that were imposed by former U.S. President Bill Clinton in 1997. Sudan lost major- if not total- access to potential markets that would import its agricultural crops, like the United States of America or Europe. Moreover, in 2020, which was the year of the first filling of the GERD, COVID-19 hit, which affected the agricultural sector.

According to a research paper by the University of Gezira, the COVID-19 pandemic affected all farmers in Sudan, as crop exports either decreased drastically or were halted for a significant amount of time due to the restrictions on movement and travel. This resulted in excess availability of crops inside Sudan, and led to low prices of crops and eventually a decrease in the number of workers needed for the agriculture industry in Sudan, as the income from this industry decreased and no longer became a valuable source of income for many people who used to work in agriculture inside Sudan.

Tarig Al-Tahir, an agriculture businessman and a crops exporter from Damazin, Blue Nile State, said he used to use rainwater to grow sesame and corn in a 3,000 feddans land since 2011, but he stopped all farming in 2021 due to the growing costs of cultivating crops.

“It costs me 50% more than the selling price to grow sesame. The rent for a feddan of agricultural land in the Blue Nile State is approximately $5,300 USD these days. Agriculture became more of a burden and loss for me and the rest of those in the agriculture industry regardless of their farming system due to low prices of crops, small revenue, increase in the prices of renting agricultural lands in the Blue Nile State. Loans and other kinds of support from the Farmer’s Commercial Bank either became insufficient or unavailable for us working in agriculture. Prices of crops sold decreased due to the increase in prices of logistic services, and also the low demand for the crops produced. As for the increase in costs of production, they increased due to economic inflation mainly” Al-Tahir explained.

Even Sudanese citizens who were not inconvenienced by the pandemic did not profit because the supply chains were in jeopardy. Also, in 2020, Sudan drowned in the most horrific water floods in a hundred years. According to Sebastian Sterl, a researcher in climate services for renewable energy at Vrije Universitansterl Brussel (VUB), the floods were not caused by the GERD, and in the future, the dam may be able to help prevent such floods.

“The floods were due to extremely heavy rainfall in Ethiopia and Sudan, which raised the water levels of the Blue Nile. It is possible that climate change is increasing the frequency of such heavy rainfall periods/events. It is most likely that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam had a small positive (i.e. mitigating) impact on these floods. Since Ethiopia started the first filling of the GERD in 2020, some of the excess water flowing in the Blue Nile was stored in GERD and did not flow downstream to Sudan. The effect was probably relatively small, since GERD did not store a lot of water (compared to its full volume) yet in that year, and most of the first filling was already done before the heavy rains. The dam will be able to partially mitigate the effect of floods in the future. In the same way that Egypt's High Aswan Dam controls (to an extent) the yearly flooding of the Nile for Egypt, so will the GERD be able to control the yearly flooding of the Blue Nile and protect Sudan from extreme floods" Sterl said.

In 2021, Sudan did enjoy a little bit of political stability, but still, the economy was suffering, and the infrastructure remained fragile. The ideal conditions to determine whether the GERD will harm or help agriculture in Sudan is only when all other disrupting factors are dormant or stable. Only then a process of collecting valid and accurate data about agriculture in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin and the Nile River basin would be applicable and a clear judgment can be rendered.

“I believe that the current problems in agriculture and the yields and revenue from farming recently is due to the negligence of the government and not due to the filling of the GERD. The government didn’t buy the crops from the farmers, nor did it take genuine care of agriculture. And I think that the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam will have a positive impact on agriculture in Sudan if Sudanese people succeed in putting suitable plans and strategies related to agriculture" said Sayyid Suleiman, an irrigation engineer.

The Ongoing Geo-Hydro Crisis

Dr. Abdelwahab Al-Tayeb, an expert in the affairs of the Horn of Africa, stated in a TV interview that “there should be a military force that consists of soldiers from both Sudan and Egypt to protect the GERD as the GERD itself is located in a region with tribal unrest.”

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam may not have a drastic impact by itself on Sudan’s agriculture and soil, but it will have a severe effect when it comes to the disputes over the water shares for both Sudan and Egypt. If a military conflict should arise between Egypt and Ethiopia due to disputes over the dam, it will surely affect agricultural projects and activities in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin because Sudan will be caught in between Egypt and Ethiopia. Thousands if not millions of farmers will be forced to vacate their farms, and agricultural projects run by the government and the private sector will have to freeze.

Should either the Egyptian or the Ethiopian armies use chemical weapons, the water composition of the Blue Nile will be altered. Thus, the soil and crops in the Sudanese Blue Nile Basin will be distorted, bringing many financial losses and health problems to the people who consume these crops. Should a peaceful scenario like a diplomatic or a legal agreement between Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt materialize, then the agriculture in the Blue Nile Basin will continue and trends towards gains or losses will be more clear.

That being said, the best scenario for the diplomatic issues related to the GERD and its impact on agriculture in Sudan would be if the three countries reach a peaceful resolution in which all of them can coordinate with each other without harming the interests of the others.

To conclude, the GERD will negatively impact Sudan’s agriculture in the short term but will be of much more importance in the long run. Sudan does not only depend on the two Niles but several other farming systems.

Disclaimer: The information about the impact of the grand Ethiopian renaissance dam is predicted and forecasted based on data, studies, research papers, knowledge of researchers, professors and experts in the field, and reports by Nile Basin Initiative. It doesn't reflect the tangible impact that happened on the ground after the third filling of the grand Ethiopian renaissance dam that occurred in August/2022.

“This story was produced in June 2022, supported by InfoNile and Media in Cooperation and Transition (MiCT) in collaboration with the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) and with support from the Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, commissioned by the European Union and Federal German Government.”