2020 was an eventful year for the entire world. For Sudan in particular, it meant a raging pandemic that further crippled its economy, insecurity, and devastating floods. The combination of these crises exacerbated preexisting economic and political woes for a country in transition to democracy. However, as seen in the December 2018 revolution, Sudanese people (both at home and abroad) have self-organized into initiatives and organizations to assist fellow citizens in these tumultuous times. In particular, efforts were made to recover from the floods and combat the Coronavirus pandemic simultaneously. But with so many people rushing to help, how can there be a more effective response?

In this case, data is a critical tool to ensure clear communication, distribution, and effectiveness in crisis response across multiple humanitarian actors to serve communities who may be in need. Compiled below are the findings and analysis of a database of over 200 initiatives involved in the COVID-19 response in Sudan, and 50 initiatives that responded to the September flash floods, collected by Shabaka in September and October 2020 The response tools used, requested, and distributed have been visualized to better understand how humanitarian entities can potentially collaborate to improve response during emergency crises.

COVID-19 Response

On March 13th, Sudan recorded its first case of the novel Coronavirus. What followed was a series of frantic government decisions to lock down the country, growing case numbers, and a collapsing health system. As the virus hit Sudan during a critical time of transition in government and economic crisis, the Sudanese authorities struggled to deal with the outbreak. The effects of the pandemic and measures to control it led to increased humanitarian needs, worsening access to basic services, such as health, education, and an increase in food insecurity and unemployment. In addition, a significant increase in Gender-Based Violence (GBV) was recorded by various governmental and non-governmental agencies. Against this backdrop, misinformation and disinformation exasperated the overwhelming sentiment of disbelief in the existence of the virus itself and ruled public opinion. Many were not wearing masks or adhering to social distancing rules, while others opted to isolate at home.

Source: Youtube

The stark difference in public opinion was evident, and many responders chose their tools accordingly. At the time, given Sudan’s numerous challenges, COVID-19 vaccines were seen as a mere fantasy. It was accepted that preventing the spread and infection of the virus was Sudan’s only option.

Source: Twitter

Consequently, as seen in Figure 1, the most used COVID-19 response tool was ‘Field Awareness Raising’, which directly spoke to passing information to citizens about the virus and its prevention. Following this were ‘Social Media Posts’, ‘Posters’ and ‘Videos’ respectively – more awareness-raising tools. A few initiatives began using ‘Art’, ‘Poetry’ and ‘Songs’ as unconventional awareness-raising tools which proved to be equally as effective. Ibrahim Edris, a volunteer from Together for a Community, said, “The thing that unites people is art. These days, if you want to unite people to share your cause, you have to use art and songs because it engages the communities. You can see this in everyday life, today if you see a party, you’ll find the entire community there. Also, people understand your message more clearly [when you use art and songs] – so actually, it’s time-efficient.”

Figure 1: Bar chart illustrating top COVID-19 response tools used

Yousif Mohamed, a project manager at the Sudanese Youth Parliament for Water in Darfur explained, “when we work with displaced and marginalized groups, we use cinema or theatre. People get engaged and understand quite quickly and easily too.” This supports the potential of unconventional awareness-raising tools that should be incorporated in future responses, especially those targeting vulnerable groups.

Unlike the popularity of ‘Social Media Posts’ in the COVID-19 response, ‘Websites’ were barely used indicating a desire to digitalize response that is stunted by limited technological proficiency.

Information sharing was a key response method, however, more practical forms of preventative measure, specifically ‘Face Masks’ and ‘Sanitizers’, stood at around 10 percent. This could be attributed to the high cost of sanitizers and face masks. Still, it remains an unacceptable gap since these tools are fundamental preventative protocols to stop the virus's spread.

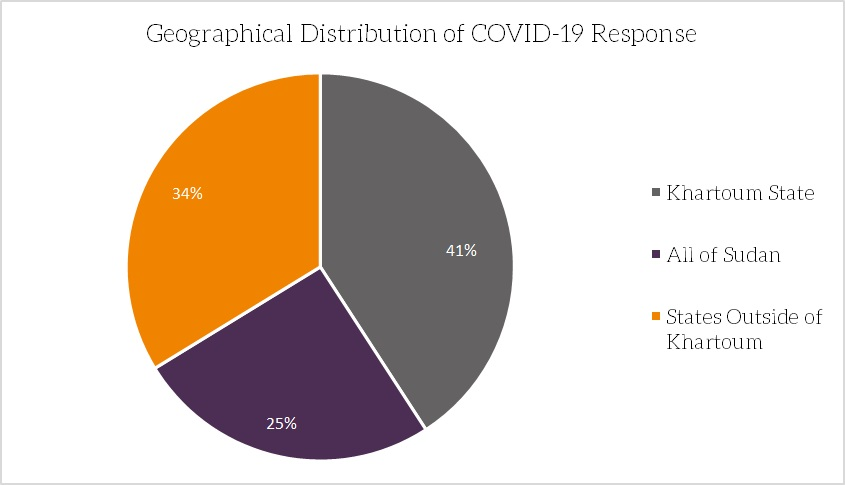

The Sudan 2021 Humanitarian Needs Overview notes, "Although Khartoum state accounts for the majority reported cases in the country, over 60 percent of all COVID-19-related deaths have been reported from outside the capital, reflecting the low capacity of the health system and testing in peripheral states." As seen in Figure 2, among the initiatives included in the database, 41% of them operated in Khartoum state alone as opposed to 34% and 25% that operated solely outside of Khartoum state and all of Sudan respectively. While the difference might seem tiny, it clearly relays that COVID-19 response among initiatives and organizations is Khartoum-centric and neglects communities in other regions, particularly, rural areas. When asked about the regional distribution of the COVID-19 response, Yousif Mohammed explained, “the need outside of Khartoum is much larger than Khartoum and new initiatives should be initiated or moved outside Khartoum to take their skills and serve other communities.” Future COVID-19 respondents should remain mindful of distributing efforts across all of Sudan’s rural and urban areas according to each region’s individual community needs and size.

Figure 2: Pie chart illustrating the distribution of COVID-19 response across states in Sudan

With that said, it cannot be ignored that operating outside of Khartoum state is accompanied by unique challenges. This was observed among the initiatives included in the database. While certain forms of requested support were shared across all initiatives, others were more tailored towards the needs of the locals. For example, referring to the effects of the ongoing security crisis in West Darfur and ethnic tensions in the COVID-19 response, Yousif explained, “the biggest challenge for us in El Geneina, West Darfur is the security problem. It was difficult for us to move around and reach more people [for awareness-raising activities] because you never know what’s going to happen. Another issue was the social issues in the community – it’s hard to bring a large group of people together; you have to approach each group alone.”

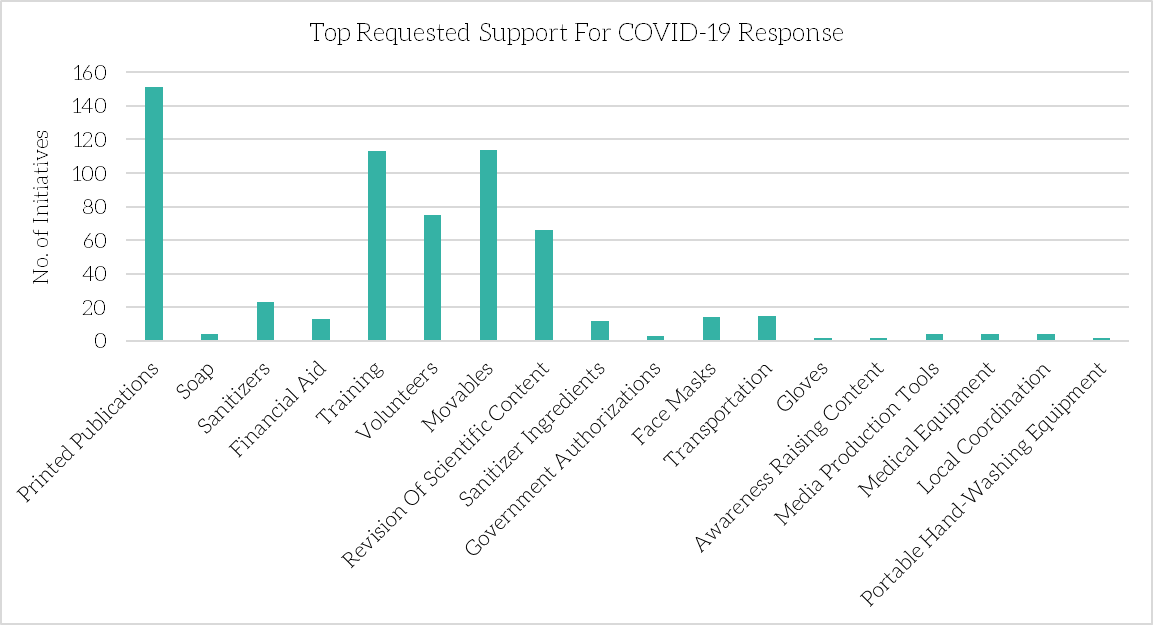

In Figure 3, the most requested forms of support by initiatives were: ‘Printed Publications’, ‘Movables’, ‘Training’ and ‘Revision of Scientific Content’. This indicates early response trends that focused on information sharing to facilitate preventative measures through awareness-raising, for example. Various forms of training were requested that ranged from social media engagement to isolation center preparation. This complements another frequently requested form of support, which called for more volunteers to engage in community-level awareness-raising activities.

Unfortunately, more practical preventative measures such as ‘Sanitizers’, ‘Face Masks’, ‘Soap’ and ‘Gloves’ distribution remain the least requested forms of support, respectively. This trend proves that response techniques are not updated, re-evaluated, or distributed evenly as most initiatives continue to focus on a singular form of response – informative awareness-raising. Such redundancy is an ailment of poor coordination and local collaboration within the humanitarian society, an element that is acknowledged by field responders. When asked about which response tool his team would have not used in earlier days, Ibrahim replied, “normal awareness raising – we shouldn’t have done it because it’s known that a lot of initiatives have done this either with us or in parallel to us. We should be alternating instead of doing the same thing, so if they’re doing field awareness then we should focus on social media posts.”

Figure 3: Bar chart illustrating the different types of support initiatives requested to aid in COVID-19 response

Nonetheless, these challenges and more are slowly being recognized and efforts to bridge them are underway. As seen in Figure 3, a few initiatives requested raw ingredients (‘Sanitizer Ingredients’) such as alcohol, ethanol, CMC powder, and containers to produce sanitizers independently. Others requested ‘Portable Hand-Washing Equipment’ which aligns with notes in Sudan’s 2021 Humanitarian Needs Overview that explained, “COVID-19 revealed WASH gaps in urban and densely populated areas such as Khartoum”. Most importantly, ‘Local Coordination’ was among the requested forms of support for the ongoing COVID-19 response.

Flash Floods Response

In September 2020, unprecedented flooding – the worst in 100 years – that lasted for weeks affected nearly 900,000 people. The most affected states were North Darfur, Khartoum, Blue Nile, West Darfur, and Sennar, leading to an estimated 2.2 million hectares of agricultural land being flooded. Paired with the unfolding pandemic and economic crises, people rendered homeless and unemployed by the floods were severely in need of humanitarian assistance.

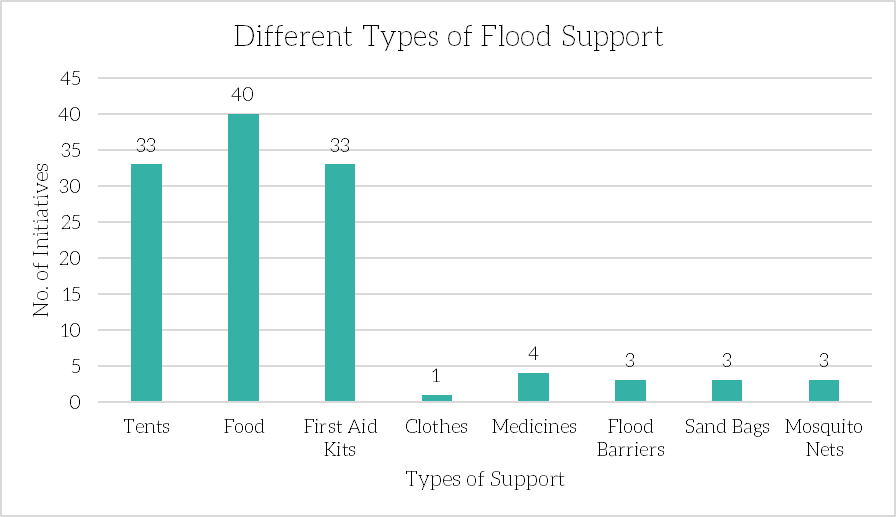

The different types of flood support as seen in Figure 4 focused on three primary items: ‘Food’, ‘Tents’ and ‘First Aid Kits’, respectively. This is generally associated with basic emergency response plans that aim to provide emergency support. Additional forms of response such as ‘Medicines’, ‘Sand bags’, ‘Flood barriers’ and ‘Mosquito nets’ also supported make-shift shelters of flood-displaced persons. Long-term aid such as education, clean water, or sanitation kits was not recorded despite the alarming risk of water-borne diseases and schools' mass destruction after the floods.

Figure 4: Bar chart representing the different forms of flood support provided by initiatives

The floods affected rural areas suffered from preceding accessibility challenges. As noted in the needs overview report, “In Jebel Marra (Central Darfur), the road to Kwila was partly washed away due to flooding. Similarly, damage to road infrastructure made it difficult to reach areas in South Kordofan and the Blue Nile, where some villages were accessed only by boat or helicopter.”

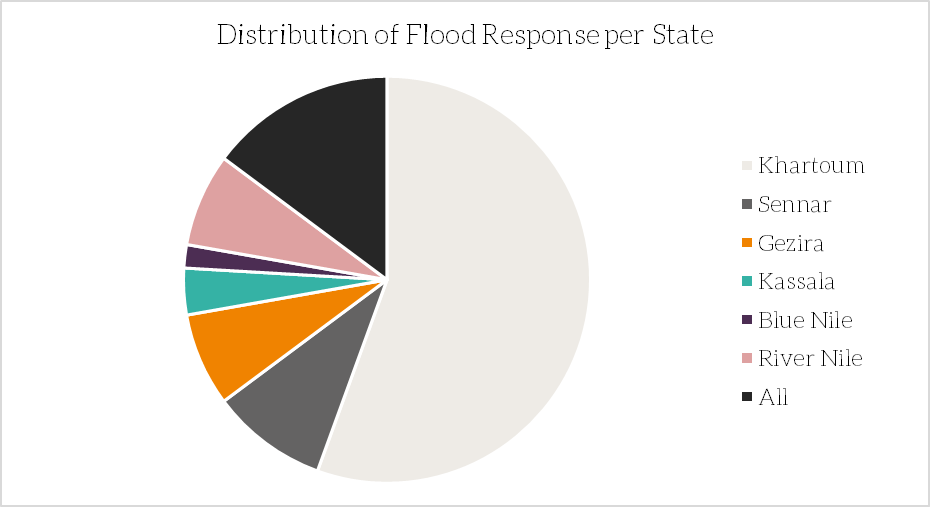

Among the initiatives in the database, as illustrated in Figure 5, efforts were concentrated within Khartoum State. Areas on the outskirt, such as Jebel Awliya, Tutti Island, and North Omdurman were covered extensively. Within other states such as Kassala, support recorded targeted Khashm el Girba and the state in general. A few initiatives overcame this shortcoming by targeting a primary and secondary state while others aimed to distributed efforts across all of Sudan.

Given the difficulty of obtaining data from some regions in the country, notably the Darfur region, we were unable to conclusively determine the types of civic aid and local initiatives that reached the region.

Figure 5: Pie chart representing the distribution of flood response across states in Sudan

Comparison

As the two crises struck Sudan simultaneously, their parallel response must be evaluated and compared to better synthesize future response plans. It is evident that the COVID-19 response was comparatively straightforward as it relied on online information, whilst the flood response mainly relied on volunteers and information resources (printed publications) for awareness-raising activities. However, in flood, he responded, the only possible means of aiding affected communities was by directly delivering or securing basic needs such as food, shelter, and medical care.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS) reports an estimated $283.5 million US dollars in total are required for the COVID-19-related Global Humanitarian Response for Sudan. Meanwhile, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) reportedly needed an estimated $70 million US dollars to assist the most vulnerable groups affected by the September floods.

It is clear that the COVID-19 response is more costly as it addresses the current pandemic and fills the underlying gaps of a poor healthcare system. Alternatively, the flood response mainly focuses on assisting affected persons to safety before forecasting the development of new infrastructure and relocation. Another contributing factor to the bias towards the COVID-19 response could be the global nature of the current pandemic, compared to the localized nature of the flash floods. This greatly affected news and media coverage of the two crises, with the COVID-19 response ultimately consuming the majority of the spotlight. This mass coverage led to higher funding and aid directed towards the COVID-19 response.

Sudan remains fragile. Building resilience to withstand these crises will require strategic and practical engagement between international humanitarian actors and local initiatives. It should not just focus on collaborating when a crisis occurs, but also preparing for crises by building resilience and support long-term recovery efforts. For instance, a recent report, issued by Shabaka, identifies the challenges faced by the Sudanese diaspora in the UK during COVID-19, which also included recommendations for the governments, organizations, and charities, on what needs to be done in the future should another pandemic or environmental disaster arise.

Implemented response activities, regions where aid was delivered, and aid requirements and needs should be recorded and available in shared reports and databases to ensure that response efforts are distributed throughout the nation and continuously upgraded despite challenges. If such transparent cooperation is achieved, the humanitarian sector could successfully pull back Sudan from the brink of disaster.

For more detailed analysis and visualizations of the data recorded, or if you’d like to contact any of the initiatives included in the database, please refer to Shabaka.