With the explosion of the popular Sudanese revolution in December 2018 – which triumphed in overthrowing the dictatorship of the Inqaz party that lasted for more than three decades – Sudanese cinema was in the midst of a revolution of its own, experiencing rebirth. It won international prizes with films made by young people in difficult and harsh conditions. These coronations came to tell the world that the Sudanese revolution is a comprehensive revolution, and not just a revolution of the hungry. At a time when people roamed the streets with bare chests shouting freedom chants, graffiti artists used to paint the walls, musicians played tunes, singers sang for the homeland, and cameras revolved in all directions to capture the legacy of these people and their great ability to persevere in the face of the arrogant dictatorship.

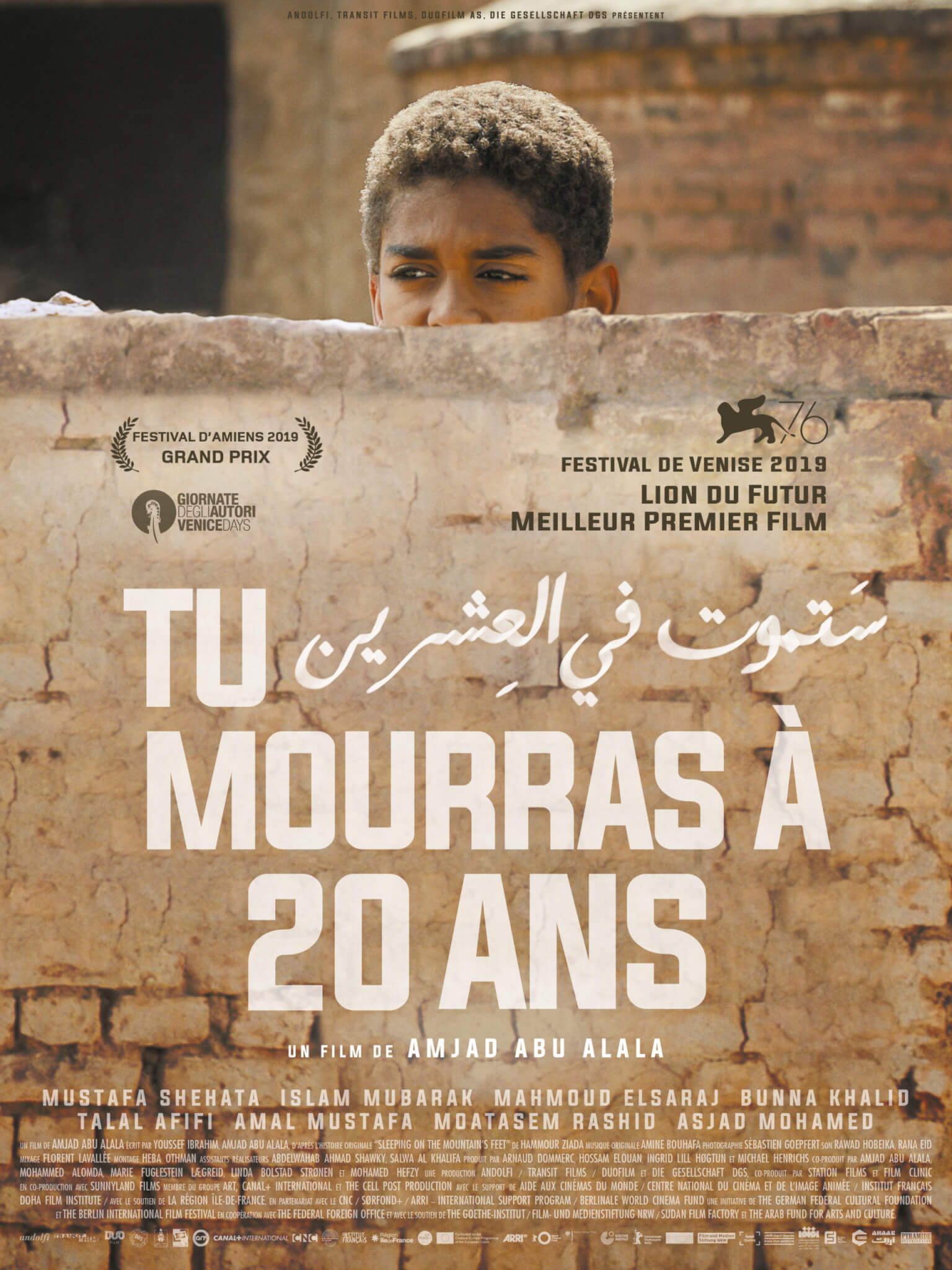

The Sudanese director Amjad Abu Al-Alaa who directed the film “You will die at 20”, won the Future Lion Award at the Venice Festival for Best Young Director. The film was also nominated for the Oscars in 2021 as the first Sudanese film to ever be nominated for this award. Furthermore, it won more than ten international awards, and it is one of the films considered a victory for the Sudanese revolution and a victory for the arts revolution.

"You Will Die At Twenty" Source: imbd

In documenting the arts and tracking the changes that the cultural and art scenes have on society, Amal Mustafa, who played the role of “Sitt Al Nissa” in the film You Will Die at 20, convenes the project’s vision. Andariya engaged Amal in a conversation about her artistic career and the complex issues facing African cinema. She calls attention to the influence of the December revolution and the hope it brought to the future of arts in Sudan. In many ways, she also emphasized the great role Sudanese women played in bringing about this change and her future in post-revolution Sudan.

"Actress Amal Mustafa" Source: Southplanet

Andariya: When was your first encounter with acting?

Amal Mustafa: I studied acting in the drama department at the Youth and Children Palace. My studies were in two stages: the children’s stage and the youth stage. It was a spring of happiness not only for us, but for all the residents of Al Mawrada and the Banat neighborhoods. It convened teachers of different backgrounds, distinct teaching methods, a unique environment, and a relatable subject matter. It was a novel experience for everyone involved. The unfamiliarity of the place to us, who did not have much exposure, still created a sense of belonging in each of us. The drama section was a world of difference in comparison to school, it became our haven and an escape. We were not only studying acting, but we also learned that acting, above all, is how we conduct ourselves. It opened up worlds that we were completely ignorant to. It also taught us team spirit, and caring for others, and our feelings towards the teachers transformed into friendships that we carry with high regard and love.

One of the things that surprised me was that the classes were co-educational. You could sit next to your male colleague without the feeling of bias or embarrassment. Our professors were firm in instilling equality, leaving us possessed by feelings of freedom, equality, and openness to others.

The Youth and Children Palace formed our awareness later on a human level. Educators like Abdul Rahim Qarni, Rashid Ahmed Issa, and Abd al-Jabbar Abdullah and the late resident Professor Hamid Jumaa, who torched a path some considered incendiary, sparking knowledge that led to enlightenment. From here, I join my teachers and my peers in their great battle to restore the Youth and Children Palace, which I hope will return to the cultural front again,in continuation of its march supporting the artistic movement and graduating generations capable of change.

Andariya: Was your first meeting with the cinema driven by passion, or were there other motives?

Amal Mustafa: Everything I do in my life I do out of passion, and my passion for cinema started at a very early age. We used to watch Egyptian and Indian films a lot at home. I loved theater and literature, especially French and Russian arts, which drove my interest in learning both languages. I personally find French to be romantic and charming, and it left no room for any other language to compete; especially when watching films directed by Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and the like. Iranian cinema is another favorite of mine. Watching films and going to the cinema became part of my daily routine. Going to the cinema itself is a magical experience, and if the movie’s context is structured, it makes the encounter much more extraordinarily.

Andariya: Tell us about your first meeting with the young director Amjad Abu Ala?

Amal Mustafa: I followed Amjad extensively online and I was impressed by his writings and thoughts about the film industry.

But my first meeting with him was at the Luxor Festival for African Cinema in 2013 after he received an award for his picture “Studio”. My first impression of him online hadn’t changed when I’ve seen how insightful and knowledgeable he was in international and Sudanese cinema. We had a long conversation throughout the event. Eventually, we became close friends.

Andariya: Tell us about your first movie experience, ‘You Will Die at 20”, and how you were chosen to be part of the cast?

Amal Mustafa: It was a total coincidence. I happened to be in Sudan when I contacted Amajd. It was a casual conversation asking him about his updates and work when he suddenly asked me to audition for his next film. I hesitated at first as I had no experience in acting. Also, I was not sure I could be fully devoted to the shooting because of my full-time job. But I eventually agreed to audition. A few days later, I received a call from Amjad that I was chosen for the “The Firest Woman” role. This blew my mind.

He later sent me the script, and as I was reading through it, I fell in love with the story and especially my character.

“The Fairest woman’ was an open book to those around her. She is sort of the sacrificial lamb, giving all with nothing in return. From the place of grief, she brings joy to others and does all the work without a clear/distinctive role. She interacts with many men, but she loves one man, in particular, sacrificing everything shehas, with no guarantee of where this relationship will lead. Her path crosses the little boy by the name of Muzammil, dancing, crying, and singing, but she remains in her place, on the sidelines of the village to protect it from death and sadness. ‘The Fairest woman’ and Sulaiman helped in building Muzamel’s soul after they have lost theirs.

"Amjad Abu Ala and Amal Mustafa" Via Facebook: Giornate degli Autori

Andariya: Did you encounter any difficulties while shooting the movie?

Amal Mustafa: Filming began on December 17, 2019, so you can only imagine the kind of in the circumstances [during the start of the December revolution]. The movement just took to the streets and during the time the cameras were rolling on set, as if fate decided this film to be born from the womb of the revolution. Shooting continued for a month, as it was hard for everyone. The film crew encompassed Sudanese and foreigners, and we would gather at the end of hard day's work around the TV to hear the news on what was happening in Sudan. As happy as we were with the filming and the movement, a cloud of sadness loomed over everyone because we did not participate in these demonstrations.

While we were bringing Muzammil back to life on the set, in contrast, the youth were reviving an entire country. I remember at the end of the last day of filming, on the bus that took us backto Khartoum, the ride turned into the largest and most beautiful demonstration. Whenever we were possessed by feelings of helplessness and sadness because we were far from what was going on in the street early on, we told each other that we were adding another face to the revolution and that cinema was a revolution in itself. I was absolutely certain that this revolution was moving forward and that we had inked a new destiny and a new life worth living.

Andariya: What does Amal want to say about the December revolution?

Amal Mustafa: This revolution is still a dream that is sometimes incomprehensible to me. I am happy that we, women, have been an integral part of the two most important revolutions in Sudan: the cinema revolution that we have always dreamed of and awaited, and the Sudan revolution.. Despite my conviction that the two revolutions have not yet been fully achieved: the revolution has not yet been fulfilled and the cinema theaters are old and inhabited by mice,It iscertainly a stepping stone, the intellectual revolution is the most influential, and while cultural change is slow and needs a lot of patience, personal effort, investments on a both a financial and devotional level. We have planted the seed, and now we have to water it and watch over it.

Andariya: Did you expect the film ‘You Will Die at Twenty’ to achieve all this success?

Amal Mustafa: I expected it even before the production of the film, as everybody did for Amjad especially after watching his short film "Studio". It was obvious through Amjad’s passion and his great knowledge of the cinema that he would become one of the directors who truly left a mark on global scale. Amjad was very meticulous in choosing the actors and the team, making sure that they were multi-national and experienced. With every expert in the team, Amjad placed an amateur Sudanese talent for an opportunity to learn andacquire skill. He also mixed professional and amateur actors, which lead to spontaneous and dynamic expression.e.

Amjad is an intelligent and ambitious director who managed to run a large team of different expertise, ages, and nationalities. This requires great skill and boldness. And as the famous film director Stephen Spielberg said, "If I manage the world in the way the crew runs the set, we will have a better and more advanced world."

‘You Will Die at Twenty’ was a unique experience that added a lot to me on an individual and artistic level, in which I got to know Amjad the director, witnessing how he used to instruct actors to do what he wanted with such ease, patience, and devotion. This was the magic recipe for the success of the film.

Andariya: Are you afraid of criticism?

Amal Mustafa: I work in a field that requires criticism and self-criticism continuously. Without criticism, a person cannot develop in any field. Therefore, I support constructive and objective criticism and I am against criticism based on subjective tools built on illusions and legacies. I fully believe that each field has its own unique and appropriate tools of criticism which must be respected and preserved. Nonetheless, the cinema remains the most spacious, open, and accommodating place for everything. I completely believe that the only tools of criticism in cinema are honesty and beauty. Was the work genuine? Did it touch your heart and race your heartbeat? Did you flutter your eyelid even for a moment and shed a tear saved for another occasion? Did the movie resonate within you long after you have left the theatre?

Any other judgment without objectivity decreases the work’s artistic value and is condemning to annihilation. I understand very much and respect a person who sees a work of art, for example, where the acting was poor, the scenario was weak, or the music did not suit the particular scene because all this falls within the standard of beauty and taste for each person. However, to classify a work as not similar to customs and traditions, or to deem it unnecessary and subject it to censorship is wrong. These are all perceptions and projections that a person must apply in their own work and not in the work of others and their artistic vision.

"You Will Die At Twenty" Source: TIFF

Andariya: “She appeared in one of the scenes, accompanied by Muzammil, the hero of the film, and against the background of the confusion that this scene provoked, the director of the film, Amjad Abu Al-Alaa, commented in one of his interviews, saying: “Amal, is a distinguished artist, who accepted to perform this scene with all courage in light of the social complications we all know about, believing in the message of art”. What is your comment on this part?

Amal Mustafa: I did not deal with the film as separate parts, but rather as a whole integrated work of art. Every scene is necessarily important to the director and his artistic vision, therefore, dropping any scene or cutting it out of its correct context would affect the entire film. These leaked scenes do not differentiate me from the rest of the scenes. There is no difference between it and the scene of Muzammil reading the Qur’an in the mosque or the scene of Sakinah while she is counting the years of her son’s life.

‘You Will Die at Twenty’ lowered the mask not only on-screen but also the masks we wear in our daily lives. These are masks that some wear deliberately and for the sake of appearance, while others wear them out of “naivety” and ignorance.

The film and the revolution gave us the opportunity to test ourselves and the damage that befell us, to correct our mistakes. In this test, many pens that were once viewed as free and enlightened fell, clashing in the battle of the revolution,giving credence to the slogans of the revolution. We won the pre-revolution battle and inevitably we will win the post-revolution battle.

The current battle of the film is a battle for tomorrow. Any victory that the film achieves today is a victory for tomorrow, for the following films and ideas, and for the generation that was intentionally deprived of cinema

I thank Amjad very much for his confidence in me, strength and steadfastness in his first experience, as difficulties and challenges were present in all stages of the film. One of the lessons I learned from him is that "Nothing is impossible unless you want it to be impossible."

Andariya: Sudanese cinema has returned to the world stage after being forced to withdrawal for more than thirty years, do you have a message for filmmakers in Sudan?

Amal Mustafa: First, I would like to say “Thank you” to everyone who believed in us and supported us. The successes achieved by these young filmmakers were not a coincidence but rather a decision they made. Their courage and boldness stemming from their love for cinema and their strong belief that no dream is impossible, even in a country where dreams and people were killed daily.

The movie ‘Talking about trees’ by Suhaib Qism Al-Bari, and ‘Khartoum offside’ by Marwa Zain, and ‘You Will Die at Twenty’ by Amjad Abu Ala, express the dreams of an entire generation. A generation that was not only deprived of realizing its dream, but was tortured, imprisoned, and killed because they dared to dream. These films broke many "taboos" and restored our confidence in ourselves and the world’s confidence in us and in the Sudanese cinema. Just as the world was dazzled by the great December revolution, they were also impressed by these films, their beauty, craftsmanship, and their context without departing from its Sudanese roots. We must not forget that these films were filmed in a time of repression of freedoms and silenced mouths. They faced great difficulties and challenges before they saw the light of day, and before people saw them raising the ceiling of freedoms with what the revolution's slogans deserve and what a people who thrived despite injustice and corruptionthey faced. These young filmmakers must not give up and they should raise the stakes higher. .

Andariya: Sudanese women played an important and pioneering role in the December revolution. Do you think they will play an equivalent role in the development and renaissance of cinema?

Amal Mustafa: Undoubtedly, Sudanese women are creative and great decision-makers in the field of culture and arts. Just as women were on the frontlines in the revolution and became icons that inspired many females in global revolutions occurring simultaneously, and consequently they will do the same in cinema.

If we look at the female characters in the film, ‘You Will Die at Twenty’, all of them are strong and resilient characters faceing life’s challenges. Every moment of defeat they were subjected to originated from a man. We saw Naima, Muzammil’s lover, whom despite the conservative community of the village, uprooted her right to love. We saw Sakina, Muzammil’s mother, and how she raised her son and bore the burden of the prophecy of his death alone prescribing his path. And despite his oppression, she walked with strength and courage even after the father's escape. Likewise, is the character of the “Fairest woman” that lover who lives on the outskirts of the village, proudly defending her love for the most intellectual man in the village, unsubscribing to social pressures.

Likewise, in the Sudanese cinema march, despite its shortness and inexperience, there are women who left their mark in the industry. There is Sarah Jadallah Jabara whom showcased a film about her father, ‘Jadallah Jabara’, one of the most important pioneers in Sudanese cinema and played a detrimental role in the emergence of African cinema. Sarah Jadallah has also made short documentaries on women living under the current status quo and on different cities across Sudan. The director Taghreed Al-Sanhouri and her cinematic works ‘Everything about Darfur’ and ‘Mother unknown’ and her long documentary film "Sudan: the Beloved", which documented the period of the secession of the South in 2011. Then the achievements of the distinguished director Marwa Zain, who first presented short films namely, ‘Salma’, ‘Randa Shaath’, ‘Game’, ‘A Week and Two Days’, and finally, her long documentary film ‘Offside Khartoum’. There are also multiple cinematic contributions of young Sudanese women such as Razan Hashem, Nahla Mahkhar, Reem Jaafar, Elaf Al-Kanzi and Eman Mirghani.

Andariya: Do you have any hopes for African cinema as you see it now?

Amal Mustafa: In the recent past, wars, political upheavals, famines, and economic decline have played a fundamental role in not giving priority to arts in general and cinema particularly in Africa. However, this does not refute that African cinema has a long history full of high-quality films. There are directors who have spent their entire lives adding to the glorious history of cinema and establishing Art schools to produce a qualified film generation, capable of competing globally and transforming African cinema into a globalized one. In the past decades, African cinema has achieved a boom and a gigantic leap that garnered the world’s attention. We note that countries such as Kenya, Senegal, Nigeria, Mali, South Africa, Mauritania, and Rwanda have conquered the cinematic scene and presented the most beautiful films.

South Africa is one of the most influential countries in the cinema movement in Africa. The film ‘The Gods Must be Crazy’ achieved great success in the 1980s and won the Montreal Film Festival award. Then from Senegal, the movie ‘Black Girl’ 1972, written and directed by Ousmane Sembèn, won the Carthage Festival award and has become a classic of African cinema. From Mali, the film ‘The Wind’, which won the Carthage Prize by its directorSouleymane Cissé.From Mauritania, the film ‘Waiting for Happiness’, which won the Cannes Film Festival award by Abdel-Rahman Sisako, and who directed his last film, ‘Timbuktu’, which won many international awards and was nominated for the Academy Awards in 2005 and nominated for an Oscar in 2014.

These are just many of the examples of highly skilled and distinctive directors and films that paved the way for a promising cinematic future for the African continent. There are also African film festivals, which have been able to gain traction and become a major market for African films, such as the Vespaco Festival in Burkina Faso, the Ancient Carthage Festival in Tunisia, and the Al-Afsar Festival for African Films, which has begun to take an international status.

Andariya: Can we expect to see Amal in new films?

Amal Mustafa: First of all, I am very happy with this experience and consider it a very special one, because it was my first cinematic experience, the first feature film by Amjad Abu Ala, the first movie after the revolution, and the first major film production in Sudan.

At the beginning of the preparatory stages of the film and before we started filming, we were not aware of the gravity of our work. Amjad succeeded in making us part of his dream, which in turn became the dream of the collective. I thank Amjad very much for his confidence in me, and I hope that another cinematic work brings us together. Before he is a filmmaker, Amjad is a lover of films and this is the secret of his distinction and success.

Andariya: Do you have a final message to the film audience in Sudan?

Amal Mustafa: “There is no cinema without an audience” and filmmakers have to regain the cinema audience that has been stolen by corrupt regimes and destroyed their taste in films. They must bridge a gap created over thirty years of malice and bad intentions, which requires time to bridge. It also requires a sincere desire to produce great films and rehabilitate theaters by making them an attractive place for the viewer – to spark the viewer's appetite and his/her desire to go to the cinema. The filmmaker is tasked with making the film and capturing the audience’s heart, but this audience, in turn, needs a comfortable chair, a clear sound and image, a good snack vendor, and a safe space to enjoy watching the film. The country must invest in the film industry and support the restoration and establishment of world-class cinemas because developing the film industry is not the responsibility of individuals but is a collective effort.

The cinema audience in Sudan should rekindle their stolen love for the cinema and spare more time for watching films. They should teach their daughters and sons the love of going to the cinema and teach them that watching a movie is not less important than reading a book. The cinema audience must also deal with the film as a product and support it by buying tickets. They must respect the rights of the film by not recording it from inside the theatre because that harms the film very much. I hope that this permanent rift between filmmakers and playwrights in Sudan will disappear because the arts are indivisible. Moreover, at this stage, efforts must be combined, roles must be complemented, and the arts must take their natural role in leading people.

Andariya: Do you have any final words?

Amal Mustafa: I am waiting for the question of "Where are you staying up this evening” and for cinema to return being amongst the daily programs of the Sudanese people. I hope that the new generation will not be deprived, just as the generation that came before who suffered the fate of being deprived of the greatestأ arts and its contribution to change and cultural awareness. I hope that every person will be compensated; those who loved cinema and were deprived of watching or making a movie for the past 30 years.

"Amal Mustafa" Picture provided by author.

This article is published as a part of a series covering how the Inqaz Regime shaped the Arts and Culture scene in Sudan over 30 years. The project is supported by the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, Arab Council for Social Sciences and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.