This article originally appeared on the author’s blog Public Health Notes and was translated and re-published with permission.

Sudanese during Eid al-Fitr prayers in Khartoum, May 2020. © AA-Mahmoud Hjaj

“Al-iltihab Alhayem” could loosely be translated to “the widespread infection”, but it certainly is a reflection of the current epidemiological situation in Sudan. Over the first weeks of 2022, social media accounts were buzzed with a public concern of a widespread respiratory infection amongst the Sudanese population. While there are several possibilities of what this widespread infection might be, the surge in COVID-19 cases reported by the government makes it a very likely scenario, compared to an outbreak of influenza or pneumonia. This article examines the likely scenarios Sudan is facing, and highlights the policy implications of these likely scenarios.

Option 1: another wave of a regular COVID-19 epidemic:

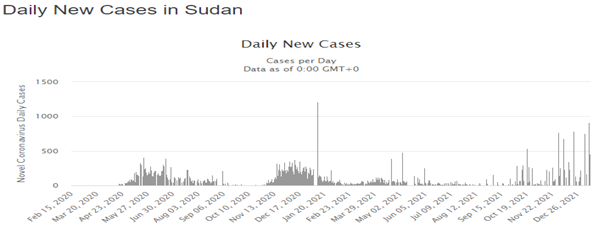

This is a likely scenario, given the spike in the number of COVID 19 cases reported in the first weeks of 2022, these numbers are largely affected by the under-reporting and the limited testing capacity of the country, this is in turn largely affected partly by the unstable political situation in the country (given the active military coup )and the absence of senior health leadership and partly by the accompanying lack of diagnostic resources in the country. The 248 reported covid19 cases are likely to be an underestimation of the true numbers. The public demonstration against the military coup manifested in public gatherings, which increase the risk for COVID19 and pretty much any other respiratory infection. The surge in COVID cases makes a fourth wave very plausible as explained in graph (1). Signs and symptoms as highlighted by patients and doctors equally are consistent with the typical COVID 19 presentation, and the percentage of the population who are fully vaccinated is extremely low.

Figure 1: COVID-19 reported cases in Sudan. Source who.int

Option 2: COVID 19 variant outbreak (Omicron)

An outbreak of the Omicron variant remains the least plausible option given the currently available information. The Ministry of Health has declared no cases of Omicron variant as of December 14th, 2021. However, in Nepal, the Omicron variant of COVID-19 has been detected in as many as 21 peacekeepers that recently returned from their mission in Sudan. If fewer than half of UK labs have the required technology to detect suspected Omicron cases, the testing strategy and capacity for Omicron cases in Sudan should be reexamined before any statements. The confusion about the Omicron variant is completely understandable, the so-called “Al-iltihab Alhayem” is often described as a flu-like disease where symptoms are typical of a common cold infection. This is typical in some of the new variants of COVID-19 as compared to the original variant- where the loss of smell/taste is reported as a symptom.

Option 3: Another respiratory outbreak (influenza, pneumonia…etc)

Other causes of respiratory infections always remain as a plausible cause for the current outbreak. It is caused by the influenza virus and is easily transmitted, predominantly via droplets and contact routes, and by indirect spread from respiratory secretions on hands and tissues. However, the limited data available on flu vaccination in Sudan and the epidemiological trends of respiratory diseases over the last few years makes it difficult to make any conclusions about a possible seasonal flu outbreak.

What does that mean for policymakers?

It could be said that Khartoum state and other parts of Sudan are faced with a respiratory outbreak. While any of the three aforementioned explanations are possible, a combination of two or more (or even other options) remains possible as well. For that, policymakers should take a rapid response in the identification of the pathogen as a priority and design a rapid response plan accordingly taking into account the overall socioeconomic and political context, cultural aspects, and public health priorities into accounts. The identification could be achieved by strengthening laboratory surveillance of viral pathogens, either independently or with the support of academic institutions and international partners. Additionally, local lab results could be cross-checked with international laboratories. A respiratory infection outbreak could generally be combated with stringent hygienic measures related to the reduction of people’s crowding, wearing face-masks, and frequent washing/disinfection of hands. The overwhelmed hospitals and the under-resourced health facilities must adjust to the current situations in terms of prioritization of patients, the readiness of more ICU beds, and availability of Oxygen cylinders and specialized chest specialists/teams. It’s worth mentioning here that the health leadership vacuum might hinder the overall process of policy-making in Sudan.

Should Sudan implement any partial/complete lockdown?

The short answer is no. The long answer is no- because firstly it might be perceived as a politically driven policy option, given that there are active protests calling for democracy (and subsequently improved health system and better health outcomes in the future). Such a message will not be regarded by the public. The law enforcement capacity currently is at its lowest, given the active back and forth tension between police and protesters in various places across major cities. Even when the country is more stable -politically-, the lockdown options is detrimental to the -already damaged- economy, and would significantly affect the daily livelihood of thousands if not millions of Sudanese people, and more will be pushed towards poverty. Disturbance of other public services, increased GBV, and other important considerations should push policymakers to think twice before making such policies.

Conclusion:

The numbers of patients complaining of respiratory symptoms are increasing, Sudan could possibly be witnessing a new wave of COVID-19 epidemic and/or another respiratory infection. Either way, preventive measures should be applied rapidly and appropriately, and the socioeconomic and political context must be regarded.