The separation of Southern Sudan from Sudan occurred in July 2011. Nonetheless, the process of nation-building continues to be very difficult as the Southern Sudanese people face major challenges in their political, social and cultural transformations. The process of self-acceptance or denial was a great shock for them in the context of joint actions to build a nation that can accommodate everyone, where everyone is demanding their own conditions in nationalism. That was not even the starting point of where Southern Sudanese were faced by challenges.

Since the signing of the Naivasha Peace Agreement in 2005, thousands of southern Sudanese returned back from the diaspora, to which they migrated due to the long civil war. They were aiming to establish a nation in which people share social, political and cultural life. Nevertheless, an unexpected shock changed the course of life between two groups. The southerners from the diaspora were named returnees, or were called “East Africa Culture”. The other group which was called the “Jallaba” (or the National Congress in the political sense) were the ones who did not flee to other countries during the civil war. These classifications constituted a major challenge in the divergence of ideas between the different groups.

Southern Sudanese from countries such as East Africa, Europe and America have returned, bringing along cultures and languages that are different from their native languages and culture. The returnees intermixed with the natives in social, political and cultural spheres, with their own intellectual, cultural and political ideologies. Language became the first barrier for the two groups. The returnees speak English and a little

Arabic (Juba Arabic) or the classical Arabic, as well as Swahili and Amhari language. The second group speaks colloquial Sudanese, classical Arabic or English. The great intermixture in the presence of these languages did not create much space for social and cultural association among the elements of the Southern community. The two groups did not reach an instant understanding about intermixing in public life, especially in the state institutions where the mutually negative perspectives had a great impact on the returning citizen or settler.

In Southern Sudan, the two groups classified themselves using the language of discrimination, which has developed to a tribal classification. The tribe became the only reference they return to when they failed to understand each other - that is, they use the mother tongue without

respect for the other person's views or affiliations. If they find themselves speaking the same language (mother tongue), the interest becomes the same. If the language is different, their attitudes are different and sensitivity develops. Noticeably, this problem was contributing to deepening of the tribal problem in the Republic of South Sudan, which has led to an ethnic political crisis.

How did the southerners live during that period of time? Angelina Dennis, a Juba university graduate shares her story and says: "I did not directly interfere with the southern citizens returning from East Africa or the outside world, for example, Europe, in public life. The university campus brought us together during school days. We shared the same environment, and I was dealing with the open type of them, and those who were willing to learn Arabic in order to get in touch with people.” And she adds: "When I was a student at Juba University, and when it was transferred to Juba, life was quite different in girls' hostel from the life I lived in Khartoum. Everyone was taking care of their own selves in terms of eating and drinking, which wasn’t the case in the community that I came from. "

Examples similar to Angelina are many in South Sudan, but Ajeng Deng had a different, contradicting view. He says that his relationship with East African returnees was not defined by the difference in culture; noting "I did not agree with them in their style, but in the end I realized that they learned a lot from East Africa. I have become involved with them in discussions, with acceptance and sometimes refusal. They associate everything they do with freedom and how they should be free, but we had a restricted freedom. "

Source: Albert Gonzalez for UNDP

Twenty-year-old Lado James was born in the camps of Uganda during the civil war. He has a different view of the Southern community. Equatorial tribes were the only South Sudanese tribes he was aware of. But recently he knew there were other tribes as well. Lado acknowledges the difficulty of dealing, not because of the difference in culture, but because of the lack of knowledge about who the others really are, and what brings them together. He said "I thought the other tribes were Northerners but in fact they were Southerners.” It was hard for him to intermix with them because of the language, “which is what I think makes the communication an obstacle between me and those settled."

The story of Angelina, who lived among the educated people, specifically the university students, may have a greater impact. She explains “we relied on partnership but they relied on individualism. In the university there were titles for different groups, such as the new Sudan and the old Sudan," she said. Describing that the new Sudan is a name given to people who eat alone, while the old Sudan meant the group shares among each other. And these are the classifications that differentiate returnees from East Africa or Northern Sudan.

Angelina's experience differed from that of Mading, who moved between Juba and Uganda, but spent most of his life in Sudan before the

Naivasha Agreement. He sees that the difference in origin is a contributing element to the large exclusion among the overlapping communities: the returnees and the settlers. He adds: "raising communities while preserving the customs and traditions of culture that extend to the larger family and clan in Sudan has a significant impact on the failure of mixing between the two groups.” Mading added that language has been a big challenge among those who speak Arabic or English, despite the presence of Arabi Juba, which is the link between the two languages.

The Republic of South Sudan has received East African and European cultures, from fashion and belief, as a result of the openness initiated by the Naivasha Peace Agreement of 2005. All these different cultures, which were rejected and accepted on different levels by the local community, have burdened the local cultures of art and folklore. For example, artists turned to Western or Eastern music in accordance with the globalization and artistic development that took place abroad, rather than developing South Sudanese art from folk music and heritage. All this pressure threatens some cultures to collapse.

But what makes it possible? Sociologist John Akoj says in the beginning of our conversation that the Southern man was placed in a dilemma of

acceptance, rejection and denial among many cultures, starting with the culture of the British and the Arabs and then the East African countries at the expense of the local cultures. The existence of psychological factors has helped in the development and hatred of a specific culture, and this can be seen in the failure to form a unified identity based on the multiplicity of tribal fabric of Southern Sudan. These problems in turn led to the emergence of social, cultural and gender based conflicts as the means for communication were limited in light of the circumstances imposed by the war.

What is the issue of language and culture in Southern Sudan? This question was asked by too many intellectuals in the capital Juba concerned

about the cultural conflict and language. Many of them have returned to the root of the problem, which is the crisis of the citizen in South Sudan, his relationship to power and culture, and the awareness about the truth of who we are as a people of South Sudan.

Many initiatives have been put forward to address these problems, especially the issue of language and tribe, in which intellectuals and youth played an important role, including the rebuilding of the nation and the social fabric in the existence of more than 64 tribes. The choice of a unified identity came up as an idea and found support from the educated minority, but the loss of confidence among the different communities had a significant impact and resulted in the continued reliance on the tribal element.

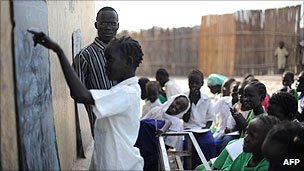

Source: BBC.co.uk

The failure of intellectuals to identify and break the barrier of communication, and failure to arrive at a true concept of identity may be caused by how since the independence of Sudan in 1956, the original problem of the Sudanese people has not been addressed; the issue of sharing power and wealth. The results of many hollow agreements emerged after the secession of South Sudan and its declaration as an independent state. Southern political leaders and intellectuals did not answer the question of: who are we? And what do we want? But perhaps a certain part of the question has been achieved by achieving separation, but it has occurred in the absence of a real vision of identity as a result of the narrow horizon of the Southern intellectual and politician in a country where illiteracy is more widespread than education.

The process of nation-building failure and the consolidation to the concept of patriotism must take a great consideration, in addition to the work on different ideologies in terms of religion, art, culture, etc., and not focusing on certain ethnic backgrounds. The lack of interaction between returnees and settlers urges the need for the review of many policies and focus on the use of tribal discrimination in the context of culture and language.

The reality, pattern of life, and behavior have changed as a result of the influence of different endemic and immigrant cultures, and they have changed many social concepts in the South Sudanese society, where the observation of daily lives of the two groups in society confirm the existence of mistaken divisions, which led to social disintegration. Who would accept such shortcomings at this time, when the rebuilding of moral and social foundation is crucial to a culturally and linguistically rich society in the modern state of South Sudan?