Ensuing a grinding and crippling civil war, the Lost Children of Sudan finally lay the on the shores of the American dream. The road was not easy for 29 year old Gai Nyok to enter the world of American diplomacy as ambassador to the United States. The man barely escaped death when he fled South Sudan to refugee camps in Kenya and Ethiopia during the second civil war in Sudan (1983-2005).

The war forced 5 year old Nyok and his family to flee their village of Abang in the region of Equatoria to refugee camps in Ethiopia. In 2001 Nyok was granted political asylum and adopted by an American family. He finished high school and obtained his Bachelor’s degree from Virginia Commonwealth University. He later became a Thomas R. Pickering Fellow which is a dedicated government program for the rehabilitation of young people who want to work in the Department of Foreign Affairs. In November 2015, Nyok officially became a diplomat in the State Department and traveled to Venezuela on his first official mission.

Gai Nyok is one of twenty thousand children, mostly orphans, aged between five and ten, who escaped from the second civil war. The war had erupted in 1983 and ended in 2005 with the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Government of Sudan and the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) which was led by Dr. John Garang. Over twenty thousand children, known as the “Lost Children” of Sudan fled to refugee camps in Kenya and Ethiopia on foot; enduring hunger, harsh natural environments and predators along the way. While some of them survived, most of them died.

UNICEF was able to reunite more than 1,200 Lost Children with their families between 1991 and 1996. In 2001, the United States resettled about 4,000 of them in 38 cities in America. The city of Omaha, Nebraska, is home to more than 7,000 Sudanese refugees.

Renowned chess champion Majur Juac is a “Lost Child” who taught himself how to play chess. When he first arrived in the United States in 2005 as a refugee from Kenya, he worked as a security guard at a school in the outskirts of Washington, DC. He became famous overnight by coincidence in New York City and later became a chess coach. Majur says that he mastered chess while playing at the refugee camp to distract himself from the hunger and emptiness that he used to feel.

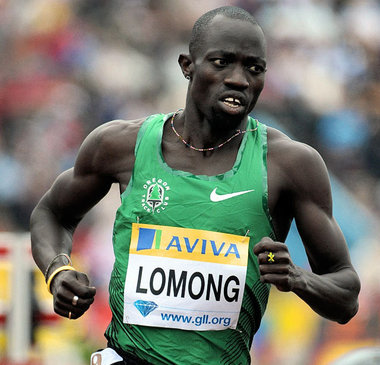

Many books and films shed light on the tragedy of the Lost Children of Sudan and the civil war that killed about 2.5 million civilians. “Escaping for my Life” is a book by Lopez Lomong, Lost Child and famous American runner, who arrived in the United States in 2001 at the age of sixteen and became a citizen in 2007. He represented the United States in several major sports events.

“The Good Lie” is the latest film production about the Lost Children of Sudan. It was produced in 2014, directed by Philip Vlardoa, filmed in South Africa and the city of Atlanta, Georgia in the United States States. The movie starred international South Sudanese Artist Emmanuel Jal who used to be a child soldier with the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) before he was adopted by the late British aid worker Emma Macon- wife of Riek Machar the current opposition leader & vice president of South Sudan. Jal became an international artist and advocate for peace and an ambassador to the United Nations. The movie also starred Ger Duany who is also a Lost Child whose dream was to become a famous movie star.

Many of Sudan’s “Lost Boys” also became famous basketball players who are known to the American public for their basketball skills such as Ater Majok, Kyot Davani, Deng Gai, Benin Gabriel, Lual Deng, Aju Deng and Adel Deng, among others

However, despite stories of success, the road to fame and financial prosperity was not passable for many of the lost children of Sudan in the United States. A study in 2005 showed that 20% out of a sample of 300 Lost Children suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a disorder that often affects those who were exposed to painful situations because of wars. Others fell victim to drug abuse while others worked in unskilled jobs and suffered from low wages and poverty.

When we look at the prestigious positions that some Lost Children have reached and compare it with the state of the nation of South Sudan, we find that there is no parity. A land with so much talent and enormous manpower should be making headway and not infighting or suffering from famine and mass murder. We hope that the Lost Children of Sudan who were able to find themselves in fortunate arenas will play a bigger role in saving the great South Sudan.